You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

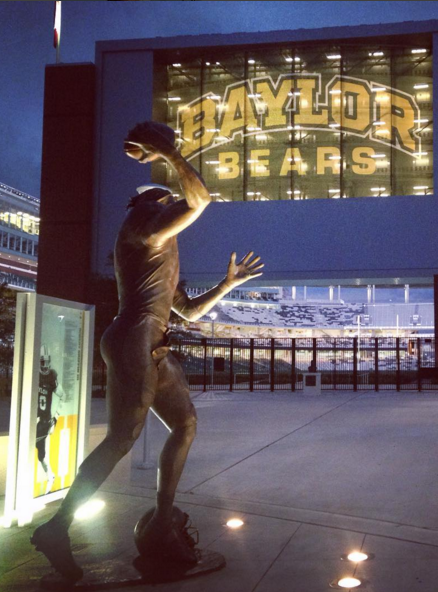

Baylor University's McLane Stadium

Jake New

WACO, Texas -- When Grant Teaff arrived at Baylor University to coach football in 1972, the university’s stadium was in as poor shape as its floundering team. The way Teaff tells it, the bleachers were made of splintering wood and “there wasn’t a blade of grass on the field.”

There certainly wasn’t a weight room for his players to train in. Teaff decided his team should have one, even if it was just a concrete block shoved underneath the stadium seats. He needed a way to finance the project, so he asked a well-connected friend and booster named Charlie Jones to ask around. Jones came back to the coach and told him, “I’ve got it, but I don’t think you’ll take it.”

Baylor was and remains a Baptist institution, and the Baptist Church is historically opposed to the consumption of alcohol. The money that could fund the new weight room was $50,000 worth of stock in Anheuser-Busch, the brewing company. “I’ll take it,” Teaff said to Jones, without much hesitation. “The devil’s had that money long enough.”

The story is a favorite of the retired coach, and he retells it often. This most recent account was during a three-day symposium at Baylor last week that examined the intersection of -- and tension between -- faith and sports. The theme of the conference was especially timely. With 16,000 students, Baylor is the largest Baptist university in the world. In the last five years, it has become something else, too: a big-time football school.

It’s now the kind of institution that has a football team featuring Heisman Trophy winners and top-paid coaches, the kind of team that, as of last week, was ranked No. 2 in the country and is in the running to win the College Football Playoff.

Like Teaff's deal to build the weight room with beer money, Baylor's recent success raises questions about whether it is compromising itself to participate in big-time sports. Teaff swindled the devil out of $50,000 to spruce up a run-down stadium that cost $1.8 million to build. The team now plays in a massive $266 million coliseum that is the envy of any similarly sized university, and perhaps even of those that are much larger. Repeated scandals at successful big-time college athletic programs have shown that winning can come with a cost -- not just financially, but academically and spiritually.

Pro Ecclesia, Pro Texana is Baylor’s motto. For Church, For Texas. “Integral to its commitment to God and to the church is Baylor's commitment to society,” the university elaborates in its mission statement. “In its service to the church, Baylor's pursuit of knowledge is strengthened by the conviction that truth has its ultimate source in God.”

But what of Baylor’s pursuit of a national football championship?

Pro Athletica

When asked if there’s tension between competing at such a level and remaining a Christian university, Kenneth Starr, Baylor’s president, said “the two are happily congruent.” As Christians, Baylor students and athletes are obligated to “pursue excellence,” Starr said. And for college football, excellence can mean winning the College Football Playoff.

Starr is a renowned judge and lawyer, arguing nearly 40 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court and serving as independent counsel during the investigation that led to the impeachment of President Bill Clinton. He became president of Baylor in 2010.

Like his view on Baylor athletics, the décor of Starr’s office is a congruence of faith and sports. Each windowsill is devoted to a different Baylor team. Championship rings abound, as do footballs and basketballs from notable games. Taking up nearly the entire length of his desk is a large wooden plaque featuring a Psalm printed in Chinese: “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.” In Scripture, Starr noted, there are at least 22 references to athletics.

In Scripture, Starr noted, there are at least 22 references to athletics.

“I think what that tells us is that there is something fundamentally human about competition and that it is a vital form of human activity and, I believe, of human flourishing,” he said. “We view athletics as complementary of spiritual formation. You have a moral obligation to be the very best you can be, but to do so with integrity.”

Daniel McMahon, principal of DeMatha Catholic High School in Maryland, said he thinks about the value of sports in the same way. As the leader of one of the top sports high schools in the country -- the school even has its own contract with Nike -- McMahon has seen many of his students move on to play at the college level. He doesn’t believe the ideas and values of top-tier athletics are in direct conflict with the mission of a religious institution, but he said during a panel at the symposium last week that he’s worried by much of the culture surrounding sports.

It’s a culture, McMahon said, that values a kind of strength that isn’t very Christian. Christianity, he said, is meant to see value in compassion and vulnerability, and too many coaches, especially in sports like football and basketball, teach athletes the opposite. One former college athlete speaking at the symposium said he was once told by a coach that there was "no smiling in basketball."

Unethical recruiting practices, academic fraud, and the prevalence of domestic and sexual assault are all issues that seem to appear with some regularity at institutions with successful basketball and football programs. The dark side of sports is troubling enough to see at any college, McMahon said, but especially so at religious institutions.

“Yet, when we look at the USA Today football rankings, who do we see at the top of the list?” McMahon said, pointing at the newspaper. “Notre Dame, Texas Christian University, Baylor. How come these schools are so committed to this? What are we doing in this particular arena, where success seems to be really important? I suppose a cheap answer is money. Ideally, Notre Dame with its own contract with NBC looks to make money. But, boy, that can’t be the only thing. What are faith-based institutions doing when we emphasize sports?”

Baylor’s football program has so far avoided the kinds of recruiting and academic scandals that can come with college sports, outside of a minor infraction earlier this year when two assistant coaches made impermissible contact with prospective recruits. But the team hasn’t avoided gender violence.

In 2012, a Baylor linebacker was arrested and later convicted of sexual assault. At the player’s trial, four other witnesses said that he had raped them as well. The following year, Samuel Ukwuachu -- then a freshman All-American -- was dismissed from the football team at Boise State University for “violating team rules” after a drunken dispute with his then girlfriend ended with the player putting his fist through a window. The woman later alleged that Ukwuachu hit and choked her. Just weeks after he was dismissed, Ukwuachu transferred to Baylor to play football there.

That October, Waco police received a call saying that Ukwuachu had sexually assaulted a fellow student. The victim, a women’s soccer player at Baylor, testified that she screamed “no” as Ukwuachu raped her in his apartment after homecoming.

In June 2014, Ukwuachu -- who still had not played a game at Baylor -- was indicted by a grand jury on two counts of sexually assaulting the female student. Even then, the team's defensive coordinator said he expected Ukwuachu to play this fall. In August, Ukwuachu was found guilty of sexual assault. He was sentenced to six months in jail and 10 years on probation.

Sexual assault is a famously underprosecuted crime, yet not only did local law enforcement officials move forward with the case, they successfully charged and convicted Ukwuachu. Meanwhile, according to a Baylor official who testified during the trial, the university never held a campus hearing because there was not enough evidence to move forward. Earlier this year, Texas Monthly published an article raising questions about whether Baylor officials knew of Ukwuachu’s previous violent behavior.

Baylor has since launched an internal inquiry to determine what went wrong with its investigation. A university spokeswoman said the sexual assault and Title IX policies at the university have been overhauled since the assault happened in 2013.

“No institution is immune from this issue,” Starr said in an interview last week. “We now have a very energetic training and prevention program. There has been very intense training with our football team. It's not just you go online and do some online training. If you look at the way we approach the issue of interpersonal violence, I believe a fair-minded judge would say, 'You're doing everything that you can.' And we're doing that because we believe in the human dignity of every person.”

Critics aren’t sure that the university’s Title IX policies and prevention education are the issue, however. They see the case as being related to the corrupting influence of big-time college sports -- a culture that can place winning above all else, including the safety of students. “You want to be just like the big, bad kids, Baylor?” Brian Smith, sports columnist for the Houston Chronicle, wrote after the scandal came to light in August. “Congratulations. Now, you are.”

‘An Early Rapture’

The Ukwuachu case is not the first time Baylor has had to defend the role of big-time college sports on its campus after a violent controversy. While not reaching the heights -- and level of spending -- as its football program, Baylor’s basketball team flirted with national prominence throughout the early 2000s.

In 2003, the body of a Baylor player named Patrick Dennehy was found decomposing near a gravel pit outside of Waco. He had been shot twice in the head by a teammate.

The murder was just the beginning of a case that one National Collegiate Athletic Association official said brought “incalculable disgrace” to the university and college sports. Dennehy’s death resulted in a number of related allegations about the team and its coach, Dave Bliss, coming to the surface. In 2005, the NCAA concluded an investigation into the program and doled out some of its harshest-ever sanctions -- a punishment that was a modified version of its rarely used “death penalty.”

According to the investigation, Bliss and his assistant coaches recruited “athletes of dubious character” who were “incapable” of doing the necessary academic work. Because the coaches were worried that several of the athletes would not be academically eligible to play, they recruited seven players to the team, even though the program had only five available scholarships. When, to the coaches' surprise, all seven Baylor players became eligible, the coaches decided to provide the five permitted scholarships and pay the tuition costs of the two remaining players -- including Dennehy -- under the table.

After Dennehy's death, Bliss and his assistant coaches engaged in a cover-up, with Bliss telling his players to say that the murdered student had paid his tuition by selling drugs.

Bliss had also been accused of illegally paying athletes years earlier when he was a basketball coach at Southern Methodist University, another Texas institution with a Christian foundation and a desire to compete in top-tier college athletics. Because of a much larger recruiting scandal brewing in the university's successful football program at the time, Bliss was not punished.

In 1987, SMU became the first -- and in full force, the last -- Division I institution to be slapped with the NCAA’s “death penalty” for “repeat violators,” a series of sanctions so severe that it took the football program decades to fully recover. When sanctioning Baylor in 2005, the NCAA altered the punishment to be less devastating than the full death penalty, but the case still left the university's basketball program in ruin for much of the next decade.

It was out of the ashes of the disgraced basketball team that Baylor’s football program began to flourish. When Starr first became president, he said, he visited Fred Cameron, a prominent lawyer and former member of the university’s Board of Regents, and asked him for advice.

Cameron’s reply: “Win some football games.”

Baylor winning at football was not unprecedented. After Teaff got his weight room in 1972, he transformed the program into a regional powerhouse. The real turning point came in 1974, during the season that Baylor fans call “the miracle on the Brazos,” in which the team beat the University of Texas for the first time in 17 years and later won the Southwest Conference Championship for the first time since 1924. But when Teaff retired in 1992, the team spent the next 15 years racking up losses.

Starr took Cameron’s advice to heart, and made an immediate splash as president by threatening legal action against the Southeastern Conference and Texas A&M University when Texas A&M decided to leave the Big 12 Conference, a move that many at the university feared would break up the league and leave Baylor without a big-time conference home. Texas A&M ultimately left for the wealthier SEC, but Starr's threats are credited with helping give other waffling Big 12 teams enough pause that they decided to remain with the league.

Baylor's football program’s rise in stature under Starr is frequently described as “meteoric.” In 2010, the head coach, Art Briles -- who had already begun laying the groundwork for the program’s revival two years earlier -- led the team to the Texas Bowl, finishing off the Bears' first winning season in 15 years. Baylor has since won more than 20 Big 12 conference games and its first Big 12 title since 1980. This season, Baylor is undefeated.

Then there was the construction of the $266 million McLane Stadium, an architectural and fund-raising marvel that sits on the banks of the Brazos River -- its lights shimmering in the water as a literal reflection of the university's football aspirations.

In 2005, Baylor was spending about $8 million a year on its football program, according to the U.S. Department of Education. Last year, the university spent about $28 million. Baylor now spends more than $100 million in total on its athletics department. Two decades ago, the university's athletics budget was less than $8 million. And Briles, the football team's coach, is earning $4.2 million this year.

The spending spree hasn't been limited to just sports, however. The success and higher profile of the football program have, university officials assert, helped Baylor raise $400 million since 2012 to support a flurry of construction and other projects around campus, including a new building to house the business school and a $100 million scholarship initiative. The men's basketball program, during Starr’s reign, has also rediscovered its footing, making several NCAA championship tournament appearances, and the university's women's basketball team has long been one of the best in the country. “As we would say in Christendom, it’s like an early rapture,” a member of the Baylor Board of Regents told The New York Times in 2012. “We spent 40 years wandering the wilderness. I hope this is our exit.”

When discussing Baylor during a panel at last week’s symposium, Ibrahim Jaaber, a devout Muslim and a former basketball player for the University of Pennsylvania, also evoked the story of Moses. Like the prophet emerging atop Mount Sinai with the Ten Commandments, Jaaber said, Baylor has found itself in a powerful place of influence.

“They’re going to be in a position of tremendous impact,” Jaaber said. “And so the question is, are they going to actually use that position correctly?”

‘Leaven in the Loaf’

Baylor’s mix of religion and big-time college sports is something that occupies considerable space in the mind of Darin Davis, director of Baylor’s Institute for Faith and Learning, which organizes the annual Symposium on Faith and Culture.

He said administrators like Starr and Ian McCaw, Baylor’s athletics director, share a similar mind-set, one that goes beyond game-day rituals like reciting a rudimentary prayer or thanking God after a win. "Our goal is to glorify God through our athletic program," McCaw is known to say. At Baylor, each team has its own chaplain, Davis said, and the president’s office is a staunch supporter of the Institute for Faith and Learning and its conferences.

“Here at Baylor, we see a stewardship to the larger university community,” he said. “We think in deep ways about the significance of sports.”

But Davis said he also knows that by opting into big-time college football, Baylor is part of a sporting world that may not share his views on how to think about athletics and competition. Does Baylor have to sacrifice some part of its Baptist identity and mission to remain truly competitive with these colleges? Has it already?

As the symposium wrapped up, Davis and L. Gregory Jones, the institute’s senior adviser, discussed the question over Baylor’s traditional Dr Pepper ice cream floats.

“If you have a broader religious perspective, you’re going to try and focus on the things that matter, the goods of human flourishing even while you’re also recognizing that you’re going to have to pay the salaries big-time sports coaches get, which is something that’s out of whack,” Jones said. “But I think those things can be navigated as long as you keep a larger vision in mind. You want to be a leaven in the loaf that’s continually raising that perspective. It’s an ongoing challenge that requires vigilance, and there will be mistakes.”

Events like last week’s symposium -- which drew 120 speakers and nearly 500 attendees -- can help, Davis said, by asking those in charge to “pause and take a step back.” He is already planning next year’s symposium, which, instead of sports, will be focused on the role of religion in higher learning more broadly. There’s no set date yet, Davis said, as he is waiting on the release of next season’s Big 12 football schedule.

He doesn’t want the symposium to compete with a home game.