You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

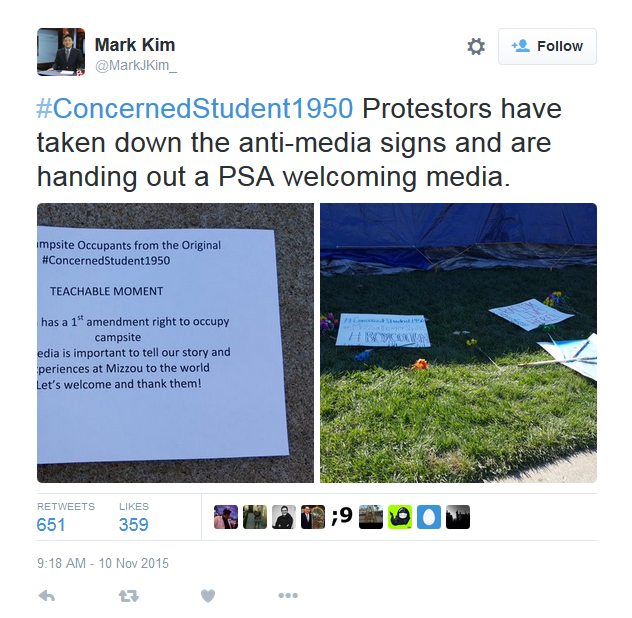

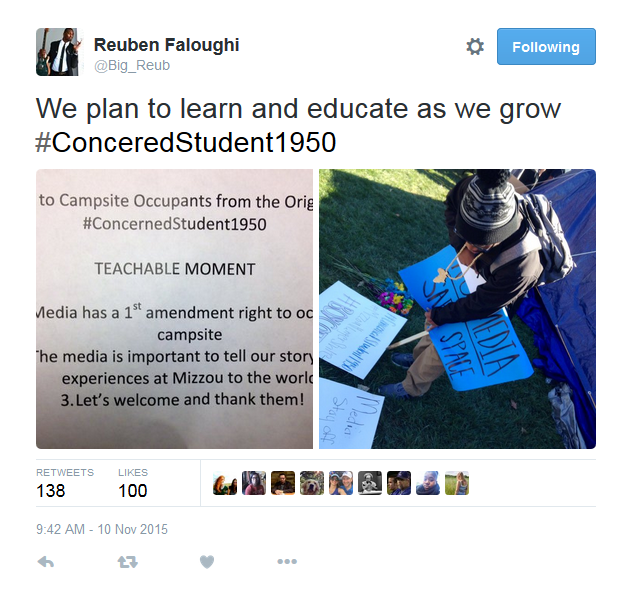

On Monday, an encampment of student protesters on the University of Missouri quad featured signs that declared “No Media, Safe Space.” By midday Tuesday, those signs had gone, and students were handing out leaflets reading “Teachable Moment.”

The fliers say, “Media has a 1st amendment right to occupy campsite” and “the media is important to tell our story and experiences at Mizzou to the world,” so “let’s welcome and thank them!”

That represented quite a change in a day.

On Monday, protesters locked arms and surrounded the camp to block press access, a Mizzou faculty member called for “muscle” to remove a student journalist, and that journalist's video of the confrontation sparked outrage, particularly on social media, over press freedom, First Amendment rights and media’s relationship with students and activists.

The video behind all the furor depicts hundreds of members and supporters of the organization Concerned Student 1950, a driving force behind weeks of protest on campus that have included both a hunger and football team strike and culminated recently in the resignation of the University of Missouri's system president and the Columbia campus chancellor.

In the video, protesters form a giant circle around the encampment, arms interlocked, chanting, at one point, “Ho ho, reporters have got to go.” Mark Schierbecker, the local photographer who filmed and upload the video, soon focuses on a student, Tim Tai, who was there taking photos for ESPN. Tai stands his ground as the protesters try to advance, pushing the press farther back.

“Back off our personal space,” someone says.

“We don’t want you to tell our story, not if you’re going to act like this,” says another.

“The First Amendment protects your right to be here and mine,” Tai insists, several times. The images of a student being blocked was particularly incongruous given that Missouri has long been proud of having a leading journalism school.

The incident echoes another episode in September when students clashed with campus journalists over race and press freedom. A group of students at Wesleyan University urged the student government to cut funds to the campus newspaper after it published opinion essay critical of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Observers watching the Missouri, Wesleyan and other debates are asking, "Can we start taking political correctness seriously now?" Others, meanwhile, are criticizing the press for focusing on First Amendment issues and not the grievances of protesters at Missouri and elsewhere about the treatment of minority students.

To experts on freedom of the press, Monday's incident was not ambiguous at all.

“Legally, the photojournalist [Tai] was on completely rock-solid ground,” said Frank LoMonte, executive director of the Student Press Law Center. “That’s not debatable at all.” The entire episode unfolded in the middle of a public quad at a public university. The protesters had every right to camp out and rally, and Tai had every right to take photos, he said.

Beyond that, LoMonte said, “All journalists use discretion from time to time as to what they shoot and don’t shoot.” Sensitive situations that warrant discretion, like funerals, arise all the time, and “all photojournalists make ethical judgment calls all day.” Whether something was going on in those tents that would necessitate a call like that isn’t clear, but, LoMonte said, “This is a historic moment, and history belongs to all of us. History is not the private property of the people who make it.”

Concerned Student 1950 did not respond to requests for comment, but as Schierbecker’s video began to get traction online, the group posted several tweets defending the signs and rejection of the media.

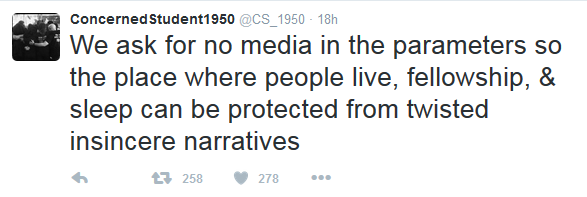

“We ask for no media in the parameters so the place where people live, fellowship, & sleep can be protected from twisted insincere narratives,” read one tweet that has since been deleted.

Others who took to social media, Twitter in particular, echoed that sentiment.

Jonathan Butler, the graduate student whose seven-day hunger strike catalyzed the protests and administrative shake-up at Missouri, explained in a Tuesday interview with The Los Angeles Times the original impetus behind the media ban. “We were having some difficult dialogues there, talking about race,” he said. “That's a very sensitive space to be in and be vulnerable in. It was necessary to keep that space very healthy, a very open space for dialogue, versus it being a space where people are going to cover a story, exoticize people who are going through pain and struggle.”

Butler also echoed charges that the press ought to have been covering the story before it got to the hunger strike stage. “You saying in that moment, 'That was the only way to cover the story' -- that wasn't you doing your due diligence,” he said.

Many of the journalists who encountered the “No Media” signs while they still stood were on the receiving end of multiple requests for media coverage from the same protesters. Since removing those signs requesting that media members keep their distance, Concerned Student 1950 has replaced those tweets with photos of the “Teachable Moment” PSA and a student removing the “No Media” signs alongside a note saying, “From original organizers! We’re learning and growing from this.”

As that debate dies down, however, another is brewing.

Near the end of the original video, Schierbecker finds himself on the wrong side of the circle, but as he approaches the tents, several people, including a University of Missouri communications professor, Melissa Click, demand that he leave.

“Who wants to help me get this reporter out of here,” Click shouts. “I need some muscle over here. Help me get him out.”

Later, in an expanded version of the video, Schierbecker captures Click behind the circle as she says to the interlinked protesters, “The work you’re doing is really important. We’ve got a lot of press trying to get in. Don’t let those reporters in.”

Some have called for Click's dismissal. Mitchell McKinney, chair of the communications department, said in a statement, “The University of Missouri Department of Communication supports the First Amendment as a fundamental right and guiding principle underlying all that we do as an academic community. We applaud student journalists who were working in a very trying atmosphere to report a significant story. Intimidation is never an acceptable form of communication.”

Click is not a faculty member at the University of Missouri’s renowned School of Journalism, however, she has held a courtesy appointment there, which “Journalism School faculty members are taking immediate action to review,” the school's dean, David Kurpius, said in a statement. “The Missouri School of Journalism is proud of photojournalism senior Tim Tai for how he handled himself,” Kurpius said. “The events of Nov. 9 have raised numerous issues regarding the boundaries of the First Amendment. Although the attention on journalists has shifted the focus from the news of the day, it provides an opportunity to educate students and citizens about the role of a free press.” (This morning, The New York Times reported that Click has cut her ties to the journalism school.)

Click issued an apology Tuesday evening. “I have reviewed and reflected upon the video of me that is circulating, and have written this statement to offer both apology and context for my actions,” she said in a formal statement. “I have reached out to the journalists involved to offer my sincere apologies and to express regret over my actions. I regret the language and strategies I used, and sincerely apologize to the MU campus community, and journalists at large, for my behavior, and also for the way my actions have shifted attention away from the students’ campaign for justice.”

The National Press Photographers Association, of which Tai is a member, reached out directly to Kurpius to express “strong concerns” over Click’s conduct Monday. “Both the students and their teachers are ‘ill informed,’” said NPPA lawyer Mickey Osterreicher about the video, which includes one student who says, “You don’t have a right to take our photos.”

“It should be understood that people do not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in a public place. Journalist Tai did not need permission to take anyone’s photograph. It is one thing to politely ask someone not to take a photograph, and quite another to try to intimidate someone from doing so,” Osterreicher said. “We hope the school administration will investigate this incident and take appropriate disciplinary action if necessary."

Yesterday's incident in Missouri is only the latest to spark concerns that free speech on campus is in danger of eroding. Some, though, are lashing back at the backlash, saying critics of students like those shunning press at Missouri trumpet the First Amendment too quickly and too hastily. “The freedom to offend the powerful is not equivalent to the freedom to bully the relatively disempowered,” Jelani Cobb wrote in The New Yorker.