You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

In announcing a set of new college accreditation measures earlier this month, Education Secretary Arne Duncan reiterated his criticism that accreditors are the "watchdogs that don't bite."

But will the department itself have more bark than bite as it attempts to crack down on those accreditors?

The administration earlier this month unveiled ambitious legislative proposals on accreditation, calling on Congress to give the Education Department the power to force accreditors to stop approving colleges where too few students graduate and many are unable to repay their loans.

Since that plan faces long odds of going anywhere in the current Congress, though, much of the attention on accreditation in the coming months will focus on how the Obama administration enforces existing federal accreditation rules.

Education Department officials say that even without a change in the law, they are now going to pay greater attention to student outcomes in their oversight of federally recognized accreditors. The department has suggested that it may take a more aggressive approach to its process of granting federal recognition to accreditors.

But it's unclear whether the administration will back up its tough rhetoric on accreditors with concrete actions against them, given some external barriers and the government's own track record.

Focus on the Recognition Process

Although the Education Department does not directly regulate accrediting organizations, it decides which accreditors carry any weight in the eyes of the federal government. The department, on a routine basis, determines whether an accreditor should be recognized by the federal government based on a range of criteria outlined in federal law and regulation. The department typically grants recognition to an accrediting agency for a period of several years, though it often shortens the time if it has concerns about an accreditor.

The department has rarely stripped accrediting agencies of their federal recognition. Since colleges must be accredited by a federally recognized accreditor in order to receive federal student aid, such an action -- especially against a large accreditor -- could have drastic consequences for college and students.

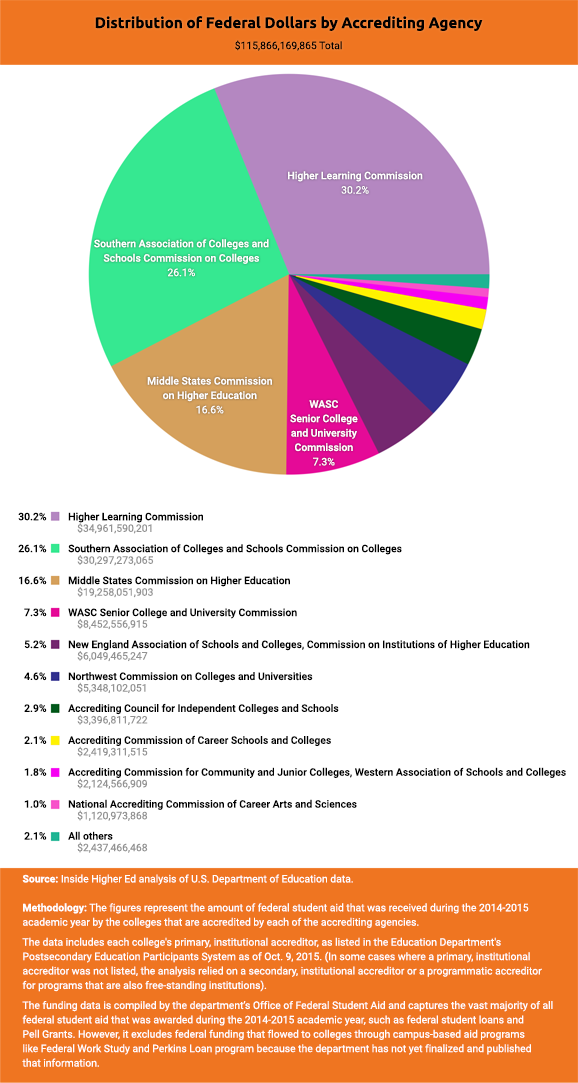

Only a handful of accrediting agencies are responsible for giving colleges access to the bulk of all federal student aid, an Inside Higher Ed analysis of department data shows.

The stamp of approval from regional accreditors opened up the most federal aid to colleges, accounting for more than three-quarters of all federal student aid in the 2014-15 academic year. Colleges accredited by national accreditors received far smaller slices of the overall federal support, but they still account for billions of dollars in funding.

If the department were to remove the recognition of nearly any of the largest accreditors, it would jeopardize the flow of at least $1 billion in federal student loans and grants to colleges.

Colleges affiliated with that accreditor would need to immediately secure approval from a different accrediting agency in order to continue allowing their students to receive federal loans and grants. And if any colleges were unable to do so and had to close, the Education Department would be stuck with the bill for wiping out students' federal loans through closed school discharges.

David Bergeron, who is a senior fellow for postsecondary education at the Center for American Progress, was an Education Department official at the beginning of the Obama administration when the department's Office of Inspector General urged the department to consider revoking the recognition of the Higher Learning Commission, the nation's largest accrediting agency. The inspector general said that the commission’s approval of a for-profit college with significant problems raised questions about the integrity of its accreditation decisions. (The commission disagreed with that finding.)

The episode opened up a range of issues and led to a congressional hearing. But as the department grappled with how to resolve those issues, officials were mindful of the size and breadth of the Higher Learning Commission, Bergeron said.

“I, nor anyone else, at the department could say with a straight face that we were going to remove the recognition of HLC,” he said. “How quickly could hundreds of institutions find new accreditors?”

The contentious case of California and other western states' community college accreditor has also highlighted what some critics view as accreditors being too big to fail. After the accreditor sought to terminate the accreditation of the troubled City College of San Francisco, the college's powerful allies -- faculty unions, politicians and the Democratic House leader Nancy Pelosi -- went after the accreditor's recognition by the federal government.

The Education Department in 2013 cited a range of problems and issued a reprimand to the accreditor -- the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges, Western Association of Schools and Colleges -- but it did not strip the accreditor's federal recognition as some CCSF supporters would have liked. Doing so would have jeopardized the accreditation of hundreds of institutions. The California's community college system is discussing switching to a new accreditor, but that process could take years.

Access to More Data

The Education Department is barred by law from setting certain minimum standards of student academic performance, a prohibition passed by Congress in 2008 after the George W. Bush administration sought, unsuccessfully, to similarly hold accreditors more accountable for student outcomes.

Still, the department sees some room for getting tougher on accreditors under the existing law. Each accrediting agency is required to have some standard, and department officials suggested that they're going to take a harder look at whether accrediting agencies are following their own self-set standards.

One of the department's goals, Under Secretary of Education Ted Mitchell said last week, is to signal to accreditors "that we're paying attention” to student outcomes and that they are “going to matter.”

As part of that effort, the department said it's going to provide its small staff that oversees accreditors with data on student outcomes and other information about the institutions they accredit.

The department will also brief the federal panel that makes recommendations about accrediting agencies on student outcomes at their next meeting next month.

Susan Phillips, chair of the National Advisory Committee on Institutional Quality and Integrity, said the committee will be discussing how it can use student outcome data -- collected by both the government and accreditors -- during its discussions.

“There’s a whole new light being shed on student achievement,” said Phillips, who is also vice president for strategic partnerships at the State University of New York at Albany. “Maybe we want to have that information front and center when we review an agency.” (This paragraph has been updated from an earlier version, which incorrectly provided an outdated institutional title for Phillips; she is no longer provost but is now a vice president.)

Some members of NACIQI, though, have for some time been pushing for accreditors to focus more on student outcomes -- or at least explain the outcomes of the institutions they accredit. And those efforts have been met with limited success.

During the last NACIQI meeting, several members of the panel posed tough questions of the Higher Learning Commission, the nation's largest accrediting organization. Panel members were concerned that the organization was accrediting colleges with single-digit graduation rates.

The committee recommended that the Education Department continue to recognize the accreditor for the next two and a half years but also require it to return before the committee this December to explain its student outcomes.

The Obama administration in September extended the accreditor's recognition, but rejected the committee’s request to compel the accreditor to appear before the committee to explain its student outcomes.

Last year, the department’s staff recommended that the Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities be found in violation of a standard relating to how frequently it monitors institutions' compliance with standards. The staff wrote that the accreditor, among several other things, should be required to provide more robust evidence that it checked to see whether its colleges were monitoring student achievement. NACIQI agreed with that determination, and the department accepted the committee's recommendation. (Note: This article has been updated from an earlier version to clarify the findings of the department's staff.)

But the accrediting organization, availing itself of new due process rights for accreditors that the Obama administration added in 2010, filed a formal appeal. And Secretary Duncan reversed the department's decision, siding with the accrediting agency. He wrote in the appeal that the department staff and NACIQI had too narrowly read the regulation.

Several panel members welcomed the department’s efforts to provide student outcomes data as a first step to focusing more on outcomes.

Simon Boehme, who was the Education Department’s appointee to the panel to represent students, has been aggressive in questioning accreditors during NACIQI meetings. He said he was optimistic that the new data would force conversations about student outcomes -- even if it will take Congress to make changes that have actual teeth.

“Hopefully some of these accreditors will decide that they don’t want to face the NACIQI or the public without having focused on student outcomes,” he said. “This provides us with the ability now to go at the heart of accreditation, which in my mind is student outcomes.”

One likely flash point will be next spring when the Education Department will have to decide whether it will continue to recognize the controversial national accrediting agency that administration officials have repeatedly criticized for continuing to approve Corinthian Colleges as that for-profit chain collapsed.

That accreditor, the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools, has been under growing scrutiny in Washington. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has demanded records from the agency as part of an investigation involving the accreditation of for-profit colleges. And a Senate investigative panel has sought records from ACICS as well as other accrediting agencies. Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, a Democrat, had a contentious exchange with the head of the accrediting agency at a congressional hearing over the summer. Warren grilled the agency over its accreditation of Corinthian Colleges in spite of various allegations and lawsuits against the for-profit college chain.

Her questions perhaps foreshadow some of the questions the agency will receive from the NACIQI next year, though the department's ultimate action on the accreditor will test the administration's tougher posture on accreditors.