You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

College and state officials in Indiana, Tennessee, West Virginia and other places where they've been working to reform remedial education are seeing dramatic increases in students completing college-level courses.

Those are the findings in a new report from Complete College America, a nonprofit group that advocates for one approach to improve remedial education known as corequisite remediation. CCA released a report Thursday showing significant gains in states that have partnered with the organization to eliminate traditional remediation.

The corequisite approach encourages colleges to take students who need remediation and place them in college-level, or gateway, English and math courses, but to pair those courses with additional supports. However, this type of remediation has faced controversy. Critics argue that colleges may not have the money for additional supports or that gateway courses become the default placement for students.

CCA, however, says fewer students drop out and more pass gateway courses with this approach.

The group found that in Indiana, after one semester of corequisite remediation, 64 percent of students passed the connected gateway math course. In Tennessee, that figure stood at 61 percent and in West Virginia at 62 percent. Nationally, without corequisite remediation, only 22 percent of students with remedial needs have completed a gateway math course after two years, according to the report.

"What's really interesting is that every one of these states and institutions within these states have developed their own unique model and regardless they're seeing similar results," said Bruce Vandal, senior vice president at CCA. "The proportion of students in remediation who are low income and students of color, when we put them in remediation, we're asking them to spend more money and spend more time and we're expanding their time to degree. But by implementing corequisite strategies, we're making a sincere effort to level the playing field and give them the opportunities other students take for granted."

Each year, 1.7 million students entering college require remediation, according to the National Center for Educational Statistics. CCA reports that 55 percent of students in remediation are eligible to receive a Pell Grant, 56 percent are black, 36 percent are recent high school graduates, and 45 percent of Hispanic students need remediation.

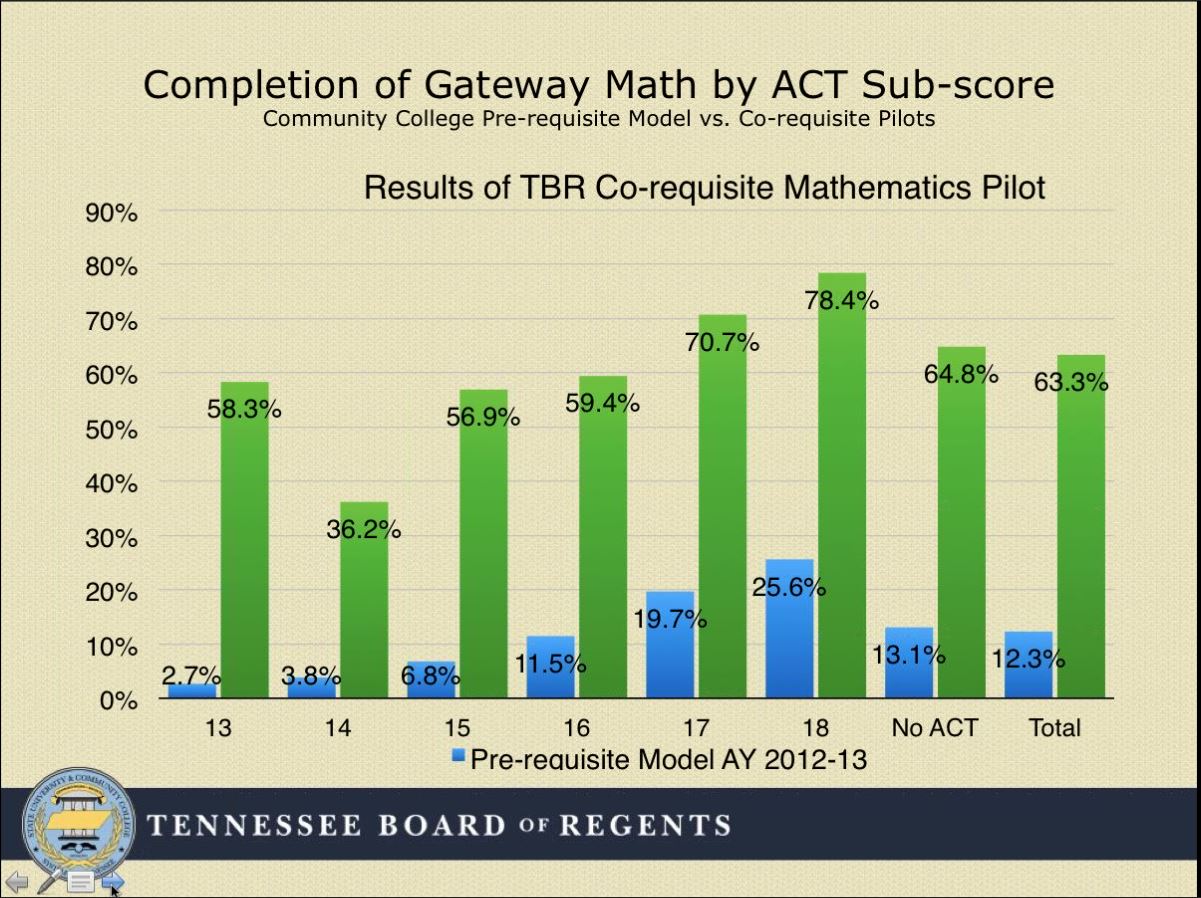

Tennessee, for instance, saw dramatic increases in students passing the gateway math course because of the corequisite course, regardless of how low students scored on the ACT in math. (The ACT is a college-readiness exam.)

Under the old remedial model, for Tennessee students who scored no more than a 13 on the ACT in math, less than 3 percent completed a gateway math course, the report found. But in the past two years, using corequisite remediation, 58.3 percent of students passed the gateway math course despite scoring a 13 in math on the ACT.

"The gains have been across the spectrum," said Tristan Denley, vice chancellor for academic affairs for the Tennessee Board of Regents. "We saw gains on writing, with low-income and underrepresented minority students."

Denley said Tennessee's approach to offering additional support to students needing remediation consisted of three hours of supplemental learning to help students gain the basic skills they need to complete the gateway course. Students also weren't graded in the supplemental courses.

"That credit-bearing class is exactly the same for all students. It's an identical learning experience, but there isn't any graded work in the [support] experience, so it's not like students are doing extra credit," he said.

Denley said this past fall the state's Board of Regents moved from a pilot program to using a corequisite approach in all the colleges the board oversees. The early results have decreased slightly but still remain higher than what was used in the past.

Vandal said so far 14 more states are committing to developing corequisite remediation strategies. But he admits that more clarity is needed to see how those reforms affect specific subgroups of students, like those who are low income or minorities.

Nikki Edgecombe, a senior research associate at the Community College Research Center at Columbia University, said enrolling more students in college-level courses would increase the number of students passing those courses, but there are still questions about whether the corequisite approach to remediation is the best option for every student.

"The next thing we have to better understand is does this serve all students as well? Are students with more significant developmental needs or students of color being served? That's the piece that needs to be understood and there are other developmental reform alternatives that are more focused on the students with developmental needs," she said.

Colleges also need better assessments to understand what skills students lack and match them with the appropriate remedy, Edgecombe said.

"I don't think anyone would dispute the corequisite model is an incredibly promising reform approach, but in the world of open-access institutions, we don't want to leave any students behind," she said.