You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The U of Wisconsin at Madison, which provides scholarships to only 8 percent of students who lack financial need.

Phil Roeder

The Pell Grant program, which the federal government spent $34 billion on in 2014, has become a way to measure how well colleges serve the underprivileged. The more Pell Grant recipients a college enrolls, the story goes, the more they’re helping to increase college access.

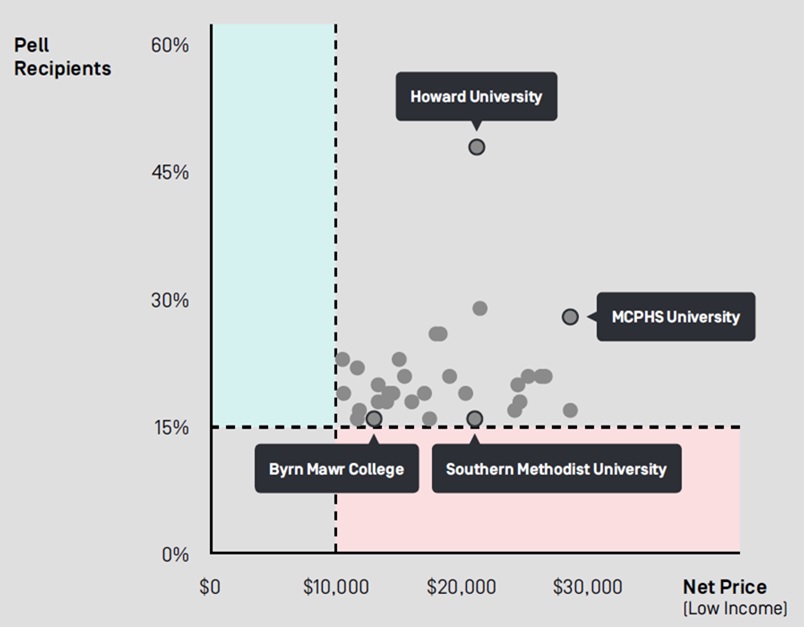

But using Pell to measure access for low-income students can do more harm than good, according to a new report. While it matters how many Pell students colleges enroll, it also matters how much those students pay.

The report, published by New America and written by senior policy analyst Stephen Burd, examined colleges' average net price for students whose families make less than $30,000. It found that, between 2013 and 2014, hundreds of colleges charged disadvantaged students more than half of their families’ yearly earnings.

“You can be enrolling a lot of Pell Grant recipients,” Burd said, “but if you’re charging them very high net prices, you may be setting them up for failure.”

In the past, colleges provided financial aid that bolstered the federal government’s efforts. But more and more, Burd writes, colleges are using their own aid strategically: institutional aid is becoming a way to recruit high-achieving students, rather than a tool to help the most disadvantaged.

Take Muhlenberg College, a private liberal arts college Burd cites in the report. In the past, says a Muhlenberg guide to the financial aid landscape, most colleges provided aid to all admitted students who needed money. But now, colleges “are increasingly reluctant to part with their money to enroll students who don't raise their academic profile.”

Burd quotes from the guide in his report, and Christopher Hooker-Haring, Muhlenberg’s dean of enrollment management, said that it was written to help students and parents understand why they may receive different offers from different colleges.

Muhlenberg’s top students, many coming from wealthy families, receive an average of $12,500 a year in merit aid, according to the report. About a third of freshmen receive aid even though they don’t have financial need, and only 8 percent of students at the college qualify for Pell Grants in the first place.

Hooker-Haring contests Burd’s portrayal, and said that students with the greatest need are receiving $35,000 to $40,000 from the college this year. “We use merit awards to help shape the class,” he said in an email, “but the largest grants are going to the neediest students.”

Most private colleges enroll more Pell-eligible students than Muhlenberg but still charge high prices. At 727 of the 824 private colleges examined, 15 percent of students received Pell Grants, but low-income freshmen still paid an average net price of over $10,000. About 30 of those colleges had endowments over $500 million.

Public colleges do better than privates, the report found, but they’re getting worse over time. Nearly half of public four-year colleges the report examined charge low-income students more than $10,000. In the 2010-2011 academic year, that number was around a third.

“As I continue this series farther along,” Burd said, “I suspect that the numbers will just continue to get worse.”

In many cases, Burd writes, colleges use Pell Grants to redirect their own aid. When the federal government increases Pell dollars, he said, these institutions feel they can spend less of their own money on needy students.

Attracting wealthy students, who can pay more, is often in colleges’ best interest. In some cases, Burd writes, colleges provide merit aid to wealthy students who aren’t high achieving. It’s cheaper to provide $5,000 merit scholarships to five wealthier students than to provide one $25,000 grant to a low-income student -- even if the low-income student is academically superior -- because the five wealthier students will be able to pay the rest of their tuition.

And when universities don’t give merit aid to already-wealthy students, they start to fall behind in student recruitment. Burd cited the University of Wisconsin at Madison, which provides scholarships to only 8 percent of students who lack financial need. The university has been losing Wisconsin high school graduates in recent years, and it will likely increase its merit aid soon.

“We've got to play in that game. We just have to,” Chancellor Rebecca Blank said back in December. “It is one of these arms-race things that I'm not happy with but I don't quite know what to do about.”

Burd thinks policy makers don’t recognize the enormity of the situation. In Washington, he writes, federal officials still believe colleges are trying to complement their efforts.

“During the Obama administration, the federal government has done all the heavy lifting,” Burd said. “So far, I haven’t seen anyone really focus on how colleges are using their institutional aid, and this merit-aid arms race that’s going on.”