You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

When it comes to finding the right approach to helping remedial students in college, pilot programs abound across the country.

But this past fall, Tennessee scaled co-requisite remediation in math, writing and reading at all of the state's 13 public community colleges. Co-requisite remediation is an approach to developmental education that places students in entry-level college courses while they simultaneously receive remedial academic support.

A new study from the Tennessee Board of Regents, which oversees the state's two-year institutions, found that while scaling up this type of remediation resulted in some small decreases in pass rates from a similar pilot program, there was overall success in students completing the credit-bearing courses compared to those who took traditional prerequisite remedial courses four years ago.

The Community College Research Center at Columbia University's Teachers College also released research today that, based on the Tennessee findings, shows co-requisite remediation to be more cost-effective than the traditional prerequisite remedial model used in 2012. However, the co-requisite approach does cost more per student.

Early Results

Systemwide teams of faculty members and administrators worked together to understand the pedagogical and practical challenges of spreading the new developmental reform across the state. Hiring more faculty and adjunct members, for example, was one of those issues, as well as asking the faculty that were already in place to teach extra classes, said Tristan Denley, vice chancellor for academic affairs for the Tennessee Board of Regents.

"Everyone did this. This was not done in a top-down fashion. Yes, it was about championing co-requisite, but as a system we coalesced around realizing how important making this change was for success of our students," Denley said.

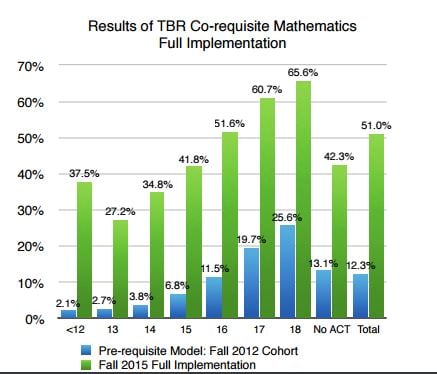

Over all, 51 percent of students in a co-requisite math course this fall passed the college-level course, compared to 12.3 percent of students who began in a remediation course and completed a credit-bearing math class within an academic year in 2012.

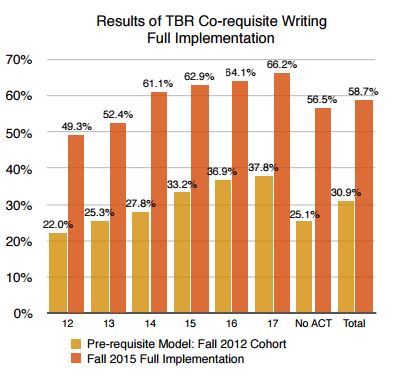

The same was true for writing, where 58.7 percent of students in the co-requisite course passed, compared to 30.9 percent who began in a traditional remediation course and completed a credit-bearing writing course in 2012.

The increases in college-level course pass rates in co-requisite math also held among minority, adult and low-income students. For example, minority student success rates increased from 6.7 percent for students who started in traditional remediation under the 2012 model to 42.6 percent under the co-requisite math approach this past fall.

But Tennessee is still seeking answers to some questions. For example, if one math co-requisite course on one campus saw better results than another college, what are the differences between the way those courses were delivered?

The various campuses had subtle differences in how they delivered the co-requisite courses. Those differences could range from some colleges choosing one instructor to deliver both the remediation and the college-level courses while others chose to split that responsibility between two instructors. Another difference could be whether students in the co-requisite course took the credit-bearing class together or were split into different sections.

"There were subtle varieties in the way schools implemented this and that was deliberate, although there's very good evidence to see the co-requisite structure itself provides an improvement in student success," Denley said.

The Cost of Scaling Up

Tennessee didn't provide any additional resources to the colleges to take the state into full co-requisite implementation. But there is a cost to revamping how colleges deliver remediation.

"With these gains in improvement and outcomes, it'd be hard to say this is not cost-effective, but we have to understand what we're looking at and what resources are needed to enable academically unprepared students to pass college-level math and writing," said Davis Jenkins, a senior research associate with CCRC and co-author of "Is Co-Requisite Remediation Cost-Effective? Early Findings From Tennessee."

The traditional prerequisite model costs less per student, Jenkins said, because it requires fewer faculty members to provide the instruction. "But because fewer students complete, the cost per successful student is high."

The CCRC study found that the co-requisite approach in math was 50 percent more efficient than the traditional prerequisite approach in enabling academically underprepared students to complete the college-level course. In writing, the efficiency gain or savings was 11 percent per successful student.

The colleges are getting more students to pass the course and they're doing it in a semester as opposed to an entire academic year, Jenkins said.

Similar cost-effectiveness tests were performed at the Community College of Baltimore County and the results were the same, he said.

"The cost per student goes up a little bit in part because of transition costs," Jenkins said. "But the cost per successful graduate, the cost we care about for society and individuals and the student, goes down dramatically. In other words, efficiency improves."

But Jenkins cautions that there are still unanswered questions surrounding the co-requisite results. The CCRC study points out that the state's move to full co-requisite implementation happened during the first semester of the Tennessee Promise program and that the system has put in place clearer guided pathways and math courses that are based on students' program paths.

The new co-requisite approach improves not only efficiency but engagement of students as well. A Center for Community College Student Engagement report in February found that students who took co-requisite courses were more engaged learners, which means they're more likely to be successful in college, according to the center.

But Evelyn Waiwaiole, the center's director, said it's time more colleges and systems scaled up their use of co-requisite and other forms of accelerated developmental education.

"[Nationally] only 40 percent of students are participating in this type of learning in English and only 31 percent are participating in this type of math. That seems discouraging, but five years ago we wouldn't even have had it that high," she said. "This is where colleges are putting in a lot of effort and we know it works because of the work at CCRC and this work at [CCCSE]. We're seeing results."