You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Since the recession, public research universities have seen greater cuts than any other sector. Slowly, state support for higher education is inching back up. But what if it never returns to prerecession levels?

That’s the question driving the Lincoln Project, which has been studying public research universities since 2013. The final report, released Thursday by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, offers wide-ranging suggestions for these universities’ financial futures.

“We know the financial model is changing,” said Mary Sue Coleman, president emerita of the University of Michigan, incoming president of the Association of American Universities and Lincoln Project co-chair. “The disinvestment from states is a national phenomenon.”

The Lincoln Project’s first four reports examined the landscape public research universities exist in: why these universities matter, what their funding models look like, why state support is going down.

Now, the final report offers advice for how research universities can thrive while embracing a new normal, such as how to find partners in the private and public sectors. As Coleman said, “This is supposed to be very realistic.”

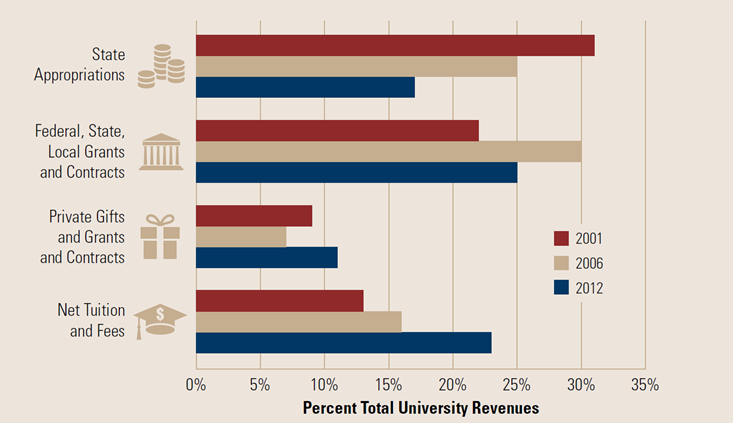

Higher education, the report says, is the “balance wheel” of state budgets. Unlike most state agencies, colleges have their own revenue streams, especially from tuition but also, for larger universities, from research grants and philanthropic gifts. They also have some control over their expenses: they can, for instance, adjust their salaries and program offerings.

And it’s easier to cut funding for higher education than for programs like Medicaid -- or even for K-12 schools -- given federal requirements and political opposition, respectively.

“Higher education is usually the last thing a state will consider,” said Coleman. “Universities are just sort of put off to the side. They aren’t an integral part of the plan.”

Coleman wants states to lay out a plan. She hopes that the report will spark discussion about states’ responsibility to their public colleges and universities, encouraging them to invest in programs like need-based financial aid.

“Public research universities are fundamentally state entities,” the report says. “Any solution to the challenges they face must begin with state governments.”

But while state support is critical, Coleman knows that it may never return to prerecession levels. And though the report does focus heavily on state support, its approach is multifaceted: it also includes recommendations for the federal government, the private sector and the universities themselves.

“By leveraging the assets that each sector can bring to the table,” Coleman said, “we can create a sustainable system to keep these research universities vibrant well into the future.”

To move forward, the report suggests that research universities focus on expanding public-private partnerships. After all, the private sector already looks to these universities for research discoveries and workforce talent, and companies provide universities with funding and employment opportunities.

But it isn’t always that simple: barriers to public-private partnerships come in the form of prohibitively complex licensing agreements. To make these partnerships easier, the report suggests simplifying those processes.

And to attract potential partners, maintaining public trust is critical, the report says. To do this, universities should establish reasonable cost and efficiency goals -- and then report those goals to policy makers, students and alumni.

In the public’s mind, rising costs are sometimes attributed to extravagant amenities -- think climbing walls, lazy rivers, luxurious apartments. But in reality, Coleman said, most of those costs are explained by declining state support, and the rest can be explained by other factors.

“We are now taking in a broader spectrum of students,” she said. “We’re happy that many students who couldn’t previously come to the university can come, but they need support.”

As a result, universities spend more on services like mental health counselors. But those costs aren’t always apparent; to earn the public’s trust, the report suggests that universities be more transparent about how costs are changing.

At the same time, the report also addresses barriers to access. While need-based aid from the states is critical, the federal government can do its part by making the federal financial aid form easier to fill out. The form is 108 questions long, and lawmakers have been trying to trim it for years.

While many of the report’s positions aren’t new, Coleman hopes the reports will break down the issues at play in a way that makes them easier to understand, showing institutions, lawmakers and businesses how they can help ensure the future of the public research university.

“It’s the intellectual infrastructure of the country,” Coleman said. “Let’s not let it slip away.”