You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

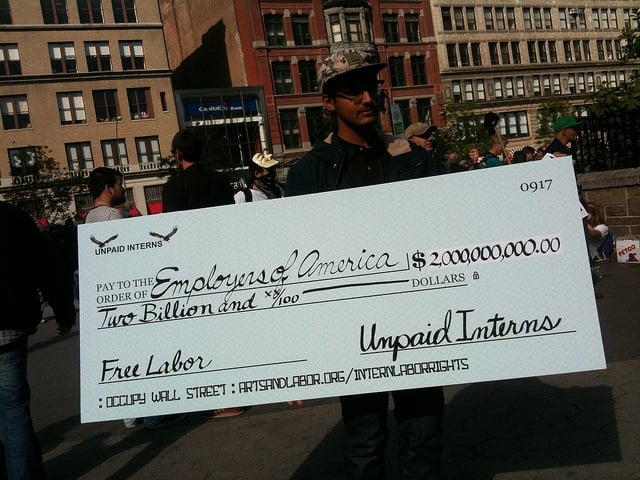

Melissa Gira / Creative Commons

During his summer internship with a New Jersey congressman, Matthew Schaller will work eight hours a day, three days a week.

He will not be paid. He is paying $3,100.

That’s the cost of a three-credit summer course at Seton Hall University, where Schaller will get credit for his work. He is a diplomacy major, and the degree program requires an academic internship.

And that’s not including the other costs: he bought a car, which he needs to travel to work and back. He’ll be paying for gas. He’s not quite sure how the university expects him to pay for credit he thinks he is earning on his own.

“They think we're financially stable,” said Schaller, a rising senior, “that we can handle all these extra expenses.”

Traditionally, the unpaid internship debate starts with the question: Should students work for free? Many say no, unless they get something in return -- like course credit.

As a result, unpaid internships that came with course credit took off. And now the question at the heart of the debate is different, and perhaps more startling: Should students pay to intern?

“Academic credit is not a currency,” said Ross Perlin, author of Intern Nation, who questions the idea that colleges should be charging. “It’s not something that people can live on.”

At Seton Hall, a group of students created a petition to protest what they see as an exploitative policy: that certain degree programs require internships -- which students complete off-campus -- and then require them to pay for the credits.

“In many ways, students are paying for the privilege to work,” said Joshua Siegel, a Seton Hall senior who’s helping to organize the petition. “It’s just another way for universities to make money.”

Siegel, also a diplomacy major, interned this semester with the Democratic Committee of Bergen County. Because he didn’t intern during the summer, he didn’t have to pay the extra tuition. When Seton Hall students intern during the school year, their flat-rate tuition doesn’t go up. But if they want academic credit for an internship during the summer -- when many students prefer to intern -- they are required to pay extra.

Even though his internship replaced classwork, Siegel still thinks it’s exploitative. He worked 13-hour weeks -- two six-and-half-hour days each week -- and paid for it as if it were a typical course, without the same kind of institutional support. He drove 25 minutes from Seton Hall to Hackensack, and he paid for his gas.

“It’s still exchange of money,” he said.

While the practice of charging for unpaid internships is not new, a new crop of students faces the fees every year, and many of them are surprised. The Washington Post reported on the Seton Hall petition Friday, giving voice to students who say that, as the nature of unpaid internships changes, their colleges are profiting from labor that is already unpaid.

Expensive, but Valuable

“As you know,” reads Auburn University’s website, “a quality college education is expensive. You know that and your parents know that.”

At Auburn, students in the School of Communication and Journalism are required to complete an internship. And in the eyes of the university, that internship is a part of an Auburn education. “Expensive? Perhaps,” reads the website. “But also very valuable.” Students are billed as if their internship were a typical course.

At universities like Auburn or Seton Hall, officials argue that internships for credit require substantial resources: faculty members help arrange the internships, communicate with students and their supervisors, grade assignments related to the work, and lead classroom discussions that take place alongside the work.

“I haven’t seen any institutions that don’t require students to pay if they are receiving credit,” said Gregory Weight, president of the Washington Internship Institute.

Most of the time, those colleges understand that they need to provide support during the internship, he added. That means helping students find an internship, ensuring they’re prepared to have a positive experience and making sure the internship aligns with their professional interests.

At Seton Hall, the university’s role depends on the program. Often, faculty members need to approve internships, speak with supervisors and grade reflection papers.

“There are a lot of features to internships that I don’t think that students often see,” said Joan Guetti, Seton Hall senior associate provost.

In Seton Hall’s diplomacy program, students can choose to opt out of the internship requirement and take another course instead. Officials say the curriculum was designed to maximize flexibility: rather than adding an additional requirement, the program built the internship into the existing credit requirement. Many students complete the internship during the year, at no additional cost.

“There’s frustration every time you need to pay for something that is difficult to explain,” said Andrea Bartoli, dean of Seton Hall’s School of Diplomacy. “But in this case it’s actually quite clear. It is part of the educational experience.”

A Class or a Job?

In many ways, the dispute over the cost represents contradictory ideas of what an internship should be: How much of an unpaid internship is educational, and how much is real work?

“We don’t consider them jobs,” Guetti said. “They’re really a class.”

For officials like Guetti, these are internships that are complemented and sustained by academic course work -- internships that, at their core, are learning experiences.

“If you see this as work that is strictly to gain professional experience so you can get a job,” Weight said, “I think the best kind of internships are not like that.”

Others say that idea is outdated and more relevant to the working economy from a couple of decades ago.

“It reflects an older idea of what an internship is,” author Perlin said. “Schools are still treating it as if it’s a service that they're providing.”

He explained that when colleges first started pushing internships, they treated them as purely educational experiences. But now internships are a way for young people to get a leg up in the working world, and students who complete them do real work. Even so, many colleges still consider the world of internships part of their turf.

And students don’t always feel the support their institutions boast. Siegel and Schaller said they are required to submit four short journal entries -- about 200-500 words each -- and attend a class for students to discuss their work. (Siegel, however, never attended the class. It met on the same day as his internship.)

Perlin recognizes that different colleges provide different levels of support, and in some cases, he sees how a fee could be justified. But more often than not, students are paying thousands -- much more than what he would call a reasonable fee. And in those cases, providing course credit doesn’t make an unpaid internship more ethical.

For some students, the fees are real barriers: many unpaid internships require students to get course credit, and students who can’t afford the tuition may have to turn down those opportunities.

At Seton Hall, Bartoli said he encourages students to intern during the year, when they won’t face an additional fee. And to support low-income students who want to intern during the summer, the School of Diplomacy raises scholarship funding.

But for Perlin, determining the ethics of unpaid internships is simple: “If they're doing work,” he said, “they should be getting paid.”