You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Students attend class at Champlain College's residential campus in Vermont.

Champlain College

Keeping general education fresh is challenging: by the time a new program takes hold, it can lose its original meaning or significance to faculty members and students alike. The result is often cafeteria-style sampling, in which undergraduates pick seemingly easy courses to fulfill various requirements over their first two years without thinking about how they might enhance their eventual majors. That’s why Champlain College has for a decade embraced its unusual model.

Champlain has constraints -- namely staying true to its pre-professional mission. The result is decidedly off-menu: a strict, interdisciplinary general education program with requirements for all four years, in which students must integrate what they’re learning in their other, more career-oriented courses. It’s not a traditional liberal arts curriculum, but Champlain’s vertical Core, as it’s known, achieves the dual aims of making the college distinct among its peers and adding texture and depth -- and an arguable edge -- to students’ pre-professional educations.

“A lot of the time professional education and graphic design education are very separate from the liberal arts -- kids go and take whatever liberal arts they want to take,” said Suzanne Glover, an associate professor of graphic design, who team teaches a required capstone course to seniors with an anthropologist as part of Champlain’s Core. “But there is no attempt to connect the two different kinds of education, so what frequently happens is that students don’t see the value or relevance of the liberal arts and how they apply to what they want to do in life.”

Through Champlain’s Core, she said, “students are a lot more engaged.”

Beyond student engagement, employers increasingly value graduates who are able to integrate their liberal arts and technical training, Glover said. “The field has changed so much that the graphic design industry is demanding that of us.” And the proof is in the placement numbers: 97 percent of 2014 graphic design and digital media graduates are employed or continuing their educations, and 88 percent are employed in areas related to their fields. Those rates are much higher than many other peer programs, Glover said. Champlain’s cybersecurity majors, among others, are similarly in demand.

So how exactly does the Core division work?

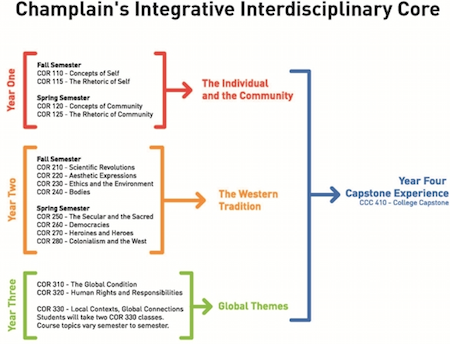

Students enter Champlain most often knowing what they want to study, from accounting to social work; it’s not a place students come to explore the liberal arts, as there are no liberal arts majors. They enroll in a majority of major classes each semester, starting as freshmen, but are required to take at least one Core general education course each semester throughout their four years. The first year focuses on concepts of the self and community, with two seminars on each in the fall and spring, respectively. The second year focuses on the Western tradition, and students may choose two of four seminars offered each semester. Junior year centers on global themes, such as human rights and responsibilities, and senior year’s Core is dedicated to a capstone experience course taught by one professional-division professor and one liberal arts professor. It culminates with a major project of the students’ design, which local professionals are invited to come view.

“We are scaffolding opportunities for students,” said Betsy Beaulieu, dean of the Core division. “We believe very strongly in hands-on experience in majors right away, and there are internships built into the pre-professional programs, to help students have as much clarity as possible for 18- or 19-year-olds about the paths they’re headed down. And we’ve built the Core to complement those experiences. [Students are] getting the soft skills employers want, along with critical and creative thinking.”

Beaulieu said the Core program is driven by inquiry, meaning that students work in groups and are encouraged to ask questions and see issues from multiple perspectives. And while Champlain is unabashed about how this kind of education might help students find jobs -- as well as its positive impact on admissions and enrollment as a marketing tool (parents reportedly love it) -- Beaulieu said it’s also about some of the more classical notions of a liberal arts education. That means setting students up for personal success and living more meaningful lives.

Not a Vocational School

“Students didn’t come to a vocational school -- we’re not just teaching students a trade regardless of what major they’re in,” Beaulieu said. “Graduates are also going to be members of communities, families and civic organizations.”

The first semester of the Core, focused on the self, for example, includes such readings as Othello; David Linden’s The Accidental Mind: How Brain Evolution Has Given Us Love, Memory, Dreams, and God; and Forty Studies That Changed Psychology. The semester ends with all students completing a self-portrait of some kind (they’ve done everything from baking a cake to painting a mirror) and a reflective essay. The subsequent community-based semester includes conversations about what makes a community good, just and sustainable, and features works by Plato, Karl Marx and Adam Smith. Ethics is woven into all elements of the Core.

Throughout the Core, there are no exams. “We’re not interested in what they can Google easily,” Beaulieu said. “They have to show they can be a creative and critical thinker. … Our graduates speak well, write well and know how to collaborate.”

Previously, Champlain had a more menu-style general education program. But when former president David Finney arrived in 2005 after a stint at New York University, he focused on a three-pronged approach to education: career training, life skills development and interdisciplinary course work in the liberal arts. That meant rethinking how and why Champlain was administering general education through its “upside-down,” immediately major-intensive curriculum.

Things haven’t been seamless -- earlier iterations of the Core were even less selective. But the program has come into its own over time. The second-year seminars, for example, on everything from “ethics and the environment” to “heroines and heroes,” are relatively new, and give students more choice.

Integration of pre-professional studies into core courses is what the Core is all about. Beaulieu said that flow the other way -- meaning Core ideas into pre-professional courses -- varies by instructor, but that it’s not unusual to have Plato come up in a marketing class, for example. Glover, in graphic design, said she doesn’t plan for discussions of core concepts in class, except for the team-taught capstone, but they naturally come up -- and she encourages them.

Craig Pepin, a longtime associate professor of liberal arts at Champlain and associate dean of assessment in the Core division, said the initial transition to the interdisciplinary general education was “challenging” in terms of faculty buy-in for many, especially in terms of disciplinary identity. “At the very least, it made some faculty very uncertain and tentative in the classroom in the first few years,” he said in an email interview.

“I think that succeeding as a teacher (and a scholar) in the interdisciplinary space requires a degree of flexibility, curiosity and humility, as well as an inclination to venture into new areas,” Pepin added, noting that interdisciplinary buy-in is no longer an issue, because new Core faculty members are now recruited based on that mission.

One such new faculty member is Michael Kelly, an assistant professor of liberal arts in the Core and Faculty Senate president with a background in rhetoric and composition.

Kelly said he didn’t begin his Ph.D. program thinking he’d teach at a pre-professional college like Champlain, but that he’s a believer in the mission. And an unexpected benefit is his colleagues, who have an unusual focus on being effective teachers, he said. That’s because the work is stretching and collaborative -- Kelly’s co-taught a capstone course in game design, for example -- and there’s little room for ego.

“There is an absence of the really esoteric disciplinary infighting that you tend to see at research-intensive institutions,” he said.

Kelly said Champlain is also a surprisingly fun place to teach because of the clear, intentional mission of the interdisciplinary core. “Students may be more inclined to ask those sorts of important questions here because there’s a name for it,” he said. At the same time, he added, there’s perhaps even more room for more integration of professional education and liberal arts, such as offering a qualitative rhetoric core course combining statistics and rhetoric targeted at economics-oriented majors.

Yet while Champlain “may not have everything figured out yet, we’re on the right track in terms of maintaining the salience of the liberal arts within a higher education environment that is increasingly professional, and a working environment that’s more complex than ever,” Kelly said.

“Redefining what it means to be a professional necessitates that the liberal arts are a really important component,” he said. “There’s a way to earn a degree in international business that looks fairly conventional -- accounting courses, finance -- but what it means to be a professional is more important than that. It means having a complex understanding of what human rights look like across the world and a deep sense of history in order not to repeat mistakes of the past. And an understanding of ways environmental considerations are tied to economies and terrorist groups and really seeing the connections across academic contexts. … That’s a mission I can get behind.”