You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

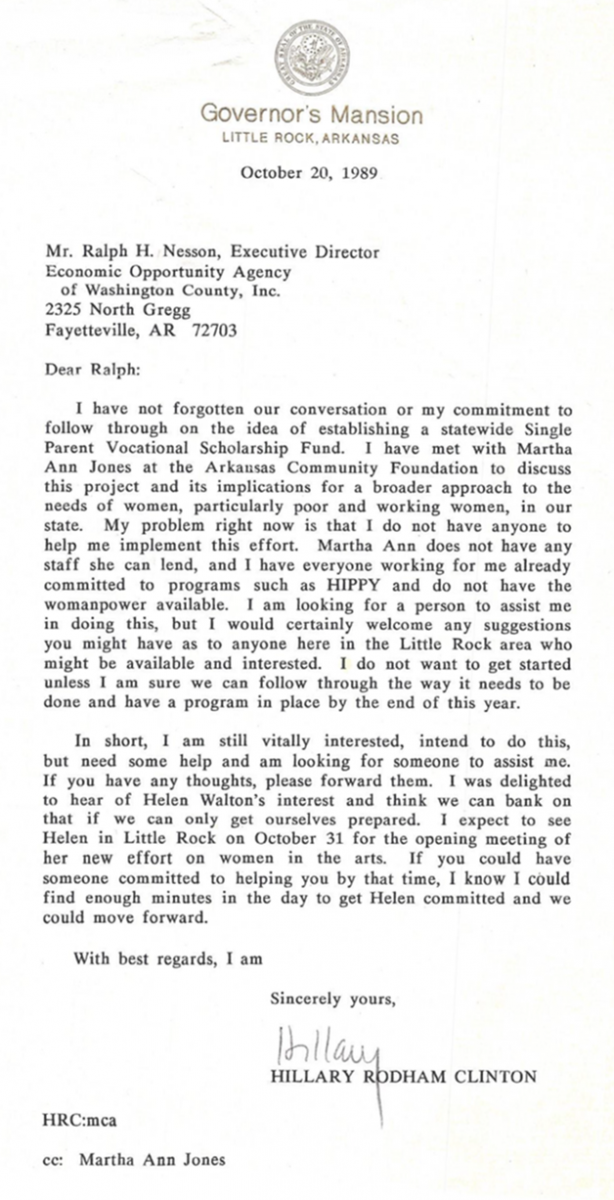

Amanda Condon, who received scholarship aid every semester, receives her diploma.

Amanda Condon

When she lost her job in 2014, Amanda Condon started thinking -- again -- about college.

She had enrolled once before, seven years earlier. At 20, she had two children, a $600 monthly child-care bill, and a full-time job to pay for it. Her days became a frenzy of work, babysitters and nights chipping away at clinical hours.

She was exhausted, and it showed.

“It didn't take long,” she said, “before I was called into my employer’s office and told that I would have to choose.”

In 2014, at 27, it was time to try again. But to make it to graduation, she would need more support. She was an unemployed single mother, and her children -- she had three now -- were 9, 7 and 2.

“There was no way,” she said, “I was going to be able to go to school, and provide for my kids, and maintain my grade average.”

She applied to the Arkansas Single Parent Scholarship Fund, a resource that she hadn’t known about the first time around. The program provides discretionary aid to low-income parents who have primary custody of their children. Condon, it seemed, fit the bill perfectly. This summer, at 29, she will graduate -- debt-free -- with an associate degree in emergency management.

The scholarship program started in 1990, when two county-level programs decided to expand statewide. Hillary Clinton, then the first lady of Arkansas, helped get the program off the ground and went on to serve as the board president for three years.

Now, the Democratic front-runner says the Arkansas program is the inspiration for a nationwide initiative that she’s proposed: Student Parents in America Raising Kids, or SPARK, would award up to a million student parents as much as $1,500 per year for expenses like child care and transportation. The scholarships would be paid for with part of the $350 billion set aside in her New College Compact.

“I don’t see why it can’t work in Iowa or anywhere in America,” Clinton said when she first announced the plan. “It’s not a lot of money, but it’s enough to help pay for gas or a babysitter.”

Clinton also hopes to increase funding for a federal program that provides grants for on-campus child care from $15 million to $250 million per year, which would create space for 250,000 more children. Both programs fit in with Clinton’s broader child-care plans with the goal of getting child-care costs below 10 percent of a family’s income.

‘So Many Other Expenses’

As tuition rises, even students without family responsibilities rack up thousands in debt -- and for single parents, getting a degree can seem nearly impossible.

Sure, there’s financial aid -- but most financial aid goes directly to the institution. That money doesn’t pay for expenses like gas or child care. Even with generous scholarship aid, many low-income single parents can’t afford to take time off from work to pursue a degree while supporting a family.

“There are many reasons why a single parent could have to drop out of school -- even with all of their bills paid to the school,” said Ruthanne Hill, executive director of the Arkansas fund.

In Arkansas, recipients use the scholarships for food, rent, groceries. Arkansas is a rural state, and students commuting hours every day use the money for gas. Others use the scholarship funds for Internet access -- which can benefit the whole family.

“If you’re dependent on a car and the car doesn’t work, you don’t go to class,” said Jay Barth, a member of the program’s Board of Directors. “If you don’t have access to computers or wireless, you’re unable to finish papers.”

Condon used the money for expenses like child care, which she needed to pay for in order to go to class. “There are so many other expenses,” she said. “It’s probably the most vital aid that I received.”

The money usually comes out to between $750 and $1,000 a semester -- but college costs are going up, and the program is trying to get everyone up to a $1,000 minimum. Right now, the amount varies by county. Some counties offer incentives based on grades, and most require their recipients to maintain a minimum grade point average.

Still, the amount is relatively small -- enough to remove barriers to an education, but not much else. “Nobody,” Hill said, “is getting rich off our scholarships.”

‘A Historically Poor State’

Over a third of Arkansas’ children grow up in poverty. Most come from families without college degrees, and Hill thinks that’s something they internalize -- that they think, “College just isn’t something that my family does.”

But just watching a parent go through college, program leaders say, changes children’s expectations.

“Arkansas is a historically poor state,” Hill said. “If we can help a single parent come out of poverty, we’re helping the entire family. The second-generational effect of our work has shown from the very beginning.”

To qualify for the scholarship, applicants must be single parents -- parents with primary custody of one or more children. Most are women, but some are men. Nearly all of them are low income, and many are victims of abuse.

After submitting their paperwork, applicants are interviewed about their plans and goals. The scholarships aren’t guaranteed -- but at that point in the process, nearly all applicants are accepted.

Beyond the money, the program also provides support services: regional offices bring in mentors and employers, and they teach workshops on skills like financial literacy, nutrition and stress reduction. They also create social settings, which helps the students meet others in similar situations.

“Single parents oftentimes end up being very isolated from other adults,” Barth said, “and certainly isolated from other adults who really understand what they're dealing with.”

Since it started, the program has awarded nearly 40,000 scholarships. And in 2014, 86 percent of scholarship recipients either graduated or continued in their education.

Still, the group estimates that it reaches only 10 percent of Arkansas single parents who could be expected to enroll in some form of higher education. It’s easier to publicize the fund to single parents already on campus; it’s harder to reach those who believe that earning a degree would be logistically impossible.

“We keep hearing, ‘you’re the best-kept secret in Arkansas,’” Hill said.

A National Program

The Arkansas fund, while a statewide program, is run at the county level. Each county has its own set of staff members, volunteers and eligibility requirements, and each county affiliate has some degree of autonomy.

While the county-based model has its limitations, Barth said that some of the program’s most critical services rely on it: the local volunteers, the mentorship programs, the financial literacy workshops.

Clinton’s program, meanwhile, would be a massively scaled-up version of Arkansas’. Under Clinton’s vision, states would have some control over the application process -- but ultimately, it would be a nationwide effort.

ASPSF leaders think such a massive program is doable -- but that it will take work. “I see the need very clearly,” Barth said. But “scaling up is always a challenge.”

While Hill wants to hear more details from Clinton, she thinks that programs like Arkansas’ would help boost state economies. In Arkansas, she sees the scholarships as an investment: when they apply, many scholarship recipients are on some form of public assistance. When they graduate, they’re earning higher salaries, paying taxes and putting more money into the economy.

“People may think we’re just another human service agency, and, of course, we do serve people -- people in great need,” Hill said, “but we’re also a great advantage to the local economy.”

Condon is more hesitant about a nationwide program. It would have to be organized carefully, she said, with a way to guard against applicants who aren’t serious about their education.

“If we’re emphasizing, ‘Oh, go to college, you can get a check,’ we might have a humongous increase in enrollment,” she said. “But if we’re not retaining those students, we’re defeating the purpose.”