You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The federal government is set to release data reports designed to help measure the performance of accrediting agencies, with metrics such as the graduation rates, debt, earnings and loan repayment rates of students who attended the colleges the accreditors oversee.

The U.S. Department of Education sent the new reports to accreditors on Monday, a couple of days before a scheduled meeting of the National Advisory Committee on Institutional Quality and Integrity, the federal panel that advises the department on which accreditors deserve federal recognition.

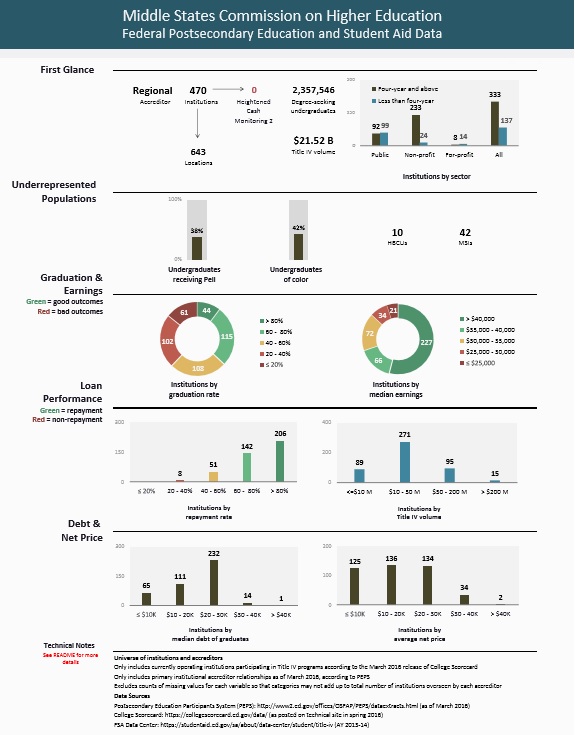

In addition to a spreadsheet, the department created visual, easy-to-read “dashboards” for 41 regional, national and programmatic accreditors, which Inside Higher Ed obtained (see below for an example and click here for the full report).

The release isn’t a surprise. NACIQI requested the data last year as part of the panel’s project to develop a “more systematic approach to considering student achievement and other outcome and performance metrics in the hearings for agencies that come before it.”

But that request came amid a sustained push by the Obama administration for accreditors to take a more aggressive consumer protection role, with a focus on student outcomes and more scrutiny for troubled colleges.

Accreditors also are on edge because the department last week recommended that NACIQI drop its recognition of a national accreditor -- the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools, which oversees roughly 245 institutions, many of them for-profits. That extraordinary decision set the table for a dramatic meeting this week, which will feature consumer advocates among dozens of scheduled speakers.

The visual reports in many ways resemble the department’s College Scorecard, which gives consumers a broad range of data about the performance of colleges. And while students and their families are unlikely to use the new charts to keep tabs on accreditors, policy makers and NACIQI probably will consult them when weighing in on whether accreditors have been adequate stewards of federal financial aid.

The data also could be a tool to compare accreditors against each other, which the department has said should be part of gauging the agencies’ effectiveness.

For example, the federal database includes the number of institutions overseen by each accreditor where less than 40 percent of students have begun to pay down their student loan principal after three years.

That was the case for 31 percent of ACICS’s member colleges, which enroll a relatively high proportion of low-income students, according to the data. In contrast, only 8 percent of colleges accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges, a regional agency, had loan repayment rates of less than 40 percent.

Similar comparisons are possible with the data reports on median graduate debt level, loan default rates, graduation rates and median earnings and other metrics. (For a table produced by Inside Higher Ed comparing most of the accreditors on a handful of key data points, click here.)

The report goes beyond student achievement, however. It includes the number of colleges an accreditor oversees that have received the harshest version of a federal sanction -- dubbed heightened cash monitoring -- that tightens the flow of federal aid to a college due to the department’s concern about that institution’s stability.

Colleges themselves also made it into the report -- the larger ones, at least -- as the department listed the performance of each institution that reeled in more than $200 million in federal aid revenue during a recent year.

'Shortening the Leash'

Ben Miller, senior director for postsecondary education at the Center for American Progress and a former official at the department, has been a prominent critic of ACICS’s approach to oversight and of the accreditation process in general, including the agencies’ “highly uneven sanctions,” which he helped document in a newly released report.

“It’s a good starting point,” Miller said of the department’s data reports. But he cautioned that the numbers would not be enough to decide whether or not to renew an accreditor’s federal recognition. “You can’t make the decision on data alone,” he said.

The metrics for graduates’ earnings and student loan repayment rates are particularly helpful, said Miller. Graduation rates are limited, he said, in part because the report lumps all institutions together, rather than breaking out the data based on the characteristics of institutions and academic programs, such as by separating community colleges from four-year institutions.

Accrediting agency officials also raised concerns about the federal data’s limitations. On a call the department hosted Monday with accreditors, some officials said they were frustrated with inaccuracies in the data and argued for the need for context to explain the numbers.

Judith Eaton, president of the Council for Higher Education Accreditation, which advocates for accreditation on behalf of colleges and universities, said the new reports are part of a “fundamental rethinking and repositioning” of the role of accreditors as gatekeepers of federal aid. She said the credibility and confidence in an accreditor increasingly will rest on data about institutional performance on student achievement.

However, Eaton said, questions remain about those metrics, and whether they measure the quality of accreditors or are really indicators of the quality of colleges.

“The way the data are presented sends a powerful message that accreditation needs to be about graduation, debt, loan repayment and earnings,” she said via email. “While these are all important, accreditation -- and higher education -- are about much more: intellectual development of students, education for life as well as work, education for effective participation in society. Yet, this is lost.”

Bernard Fryshman, a professor of physics at New York Institute of Technology and the longtime head of the country's main accreditor of rabbinical programs, was blunter. “Numbers are replacing ideas and facts and insights, and the numbers are very often wrong,” Fryshman said. “NACIQI is going to be judging accreditors on the basis of numbers that are totally irrelevant. Colleges and universities are not vocational schools.”

Peter Ewell described the new data reports as “one more step at shortening the leash” for accreditors. And that’s a good thing, said Ewell, president of the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems and a longtime expert on accreditation.

“Maybe it will nudge them in the right direction on using such measures themselves,” he said via email.

Ewell had some quibbles with the reports, saying they were a bit too busy to read effectively and agreeing with others on the limitations of federal data. But he called their release this later this week a welcome development, noting that the feds chose to focus on student achievement at colleges, rather than the activities of accreditors themselves.

“Subtly (or maybe not so subtly) showing institutional numbers instead points toward the conclusion that accreditors should take responsibility for institutions in a more direct way than has been signaled in the past,” said Ewell.