You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A much-cited 2012 study found scientists were more enthusiastic about identical applications for a lab manager position when a generic male name was at the top, versus a female one. The implications of such findings are troubling, but one possible, relatively easy solution is hiding candidates’ names during the screening process. Harder to solve are the problems posed in a new study suggesting that letters of recommendation disadvantage women scientists on the job hunt by virtue of how they discuss candidates they’re trying to help.

“Gender Differences in Recommendation Letters for Postdoctoral Fellowships in Geoscience,” published this week in Nature Geoscience, says women are only about half as likely as men to receive letters containing language that describes them as excellent, rather than just good. The study involved letters from about 500 U.S. and international institutions regarding candidates for a postdoctoral research fellowship in the geosciences at a top American university.

Interestingly, the gendered use of language was consistent across letter writers. So women, for example, weren't any more likely to describe female candidates with the kind of dynamic language that might push them into the “excellent” category than were men.

Kuheli Dutt, lead author and assistant director for academic affairs and diversity at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, said she was interested in the topic because previous studies of recommendation letters in other fields, such as psychology and medicine, made similar conclusions. But there was no such study for the geosciences, which remains “a very male-dominated discipline.”

Women in the geosciences receive 40 percent of doctoral degrees but hold less than 10 percent of full professorships, according to the study, and there's a significant leak in the faculty pipeline at the postdoctoral level.

An available institutional database of recommendation letters from 2007-12 (stripped of identifying information) made for a rich data set through which to explore the “question of whether men and women were described differently,” Dutt added. So she and her co-authors -- Danielle Pfaff, Ariel Bernstein and Joseph Dillard, all Ph.D. candidates at Columbia Teachers College, along with Caryn Block, professor of psychology and education at the college -- got to work.

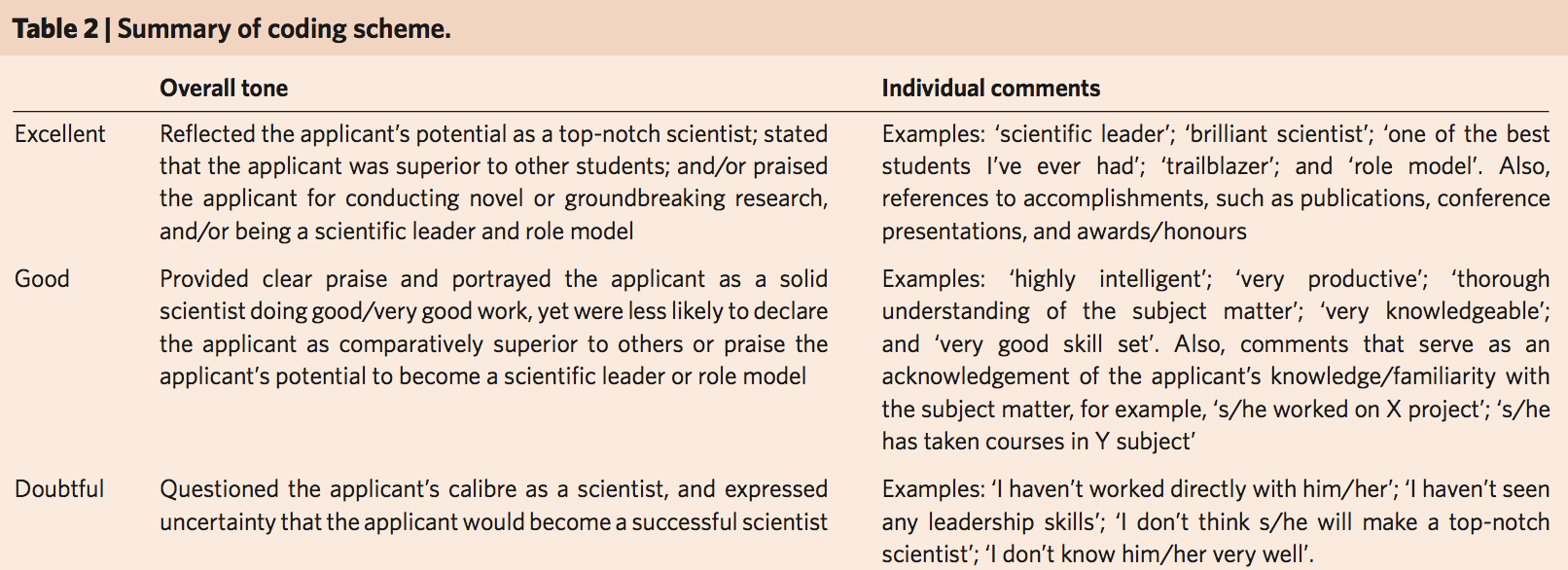

In all, they analyzed 1,224 recommendation letters from 54 countries, considering overall tone based on descriptive language. Phrases such as “scientific leader,” “brilliant scientist,” “role model” and “trailblazer” could put candidates into an “excellent” category. Lower-key phrases such as “highly intelligent," “very productive” and “very knowledgeable,” in the absence of supporting information, tended to get candidates into the “good” category.

Source: Nature Geoscience

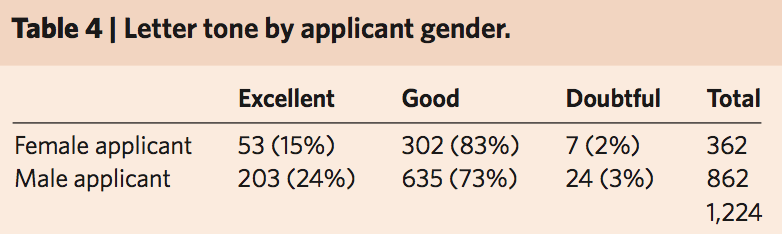

About 21 percent of letters turned out to be “excellent.” But just 15 percent of the 362 letters for female applicants were in that category, compared to 24 percent of the 862 letters for male applicants.

Source: Nature Geoscience

The study did not control for qualifications, meaning it’s possible that the men in the sample had stronger qualifications that would lead to more powerful descriptions by letter writers. Dutt acknowledged this limitation, but said that given the global nature of the data set, “it is highly unlikely that there is a worldwide systemic deficit in the quality of only the female geoscientists.” She also noted that her team’s results were similar to those of other studies that did control for application qualifications (here's one for chemistry and biochemistry), as well as implicit gender bias studies -- like the male vs. female lab manager application one.

It’s well documented that students demonstrate gender bias via language, too, in evaluating their instructors’ teaching. A study published earlier this year, for example, found that students were two to three times more likely to use the words "brilliant" or "genius" to describe male professors as they were to describe female professors. Further, the study found that the professors most likely to be called one of those terms were in disciplines -- such as physics and philosophy -- with relatively few female or black professors.

For what it’s worth, Americans tended to write much longer letters, according to the new study, but length did not correlate with gender.

So what can be done about recommendation letters’ apparent linguistic troubles? Some academics loathe recommendation letters for other reasons and have suggested that they be done away with. Is that the answer?

Dutt suggested starting with “meaningful dialogues on implicit bias, be it at an institutional level or at a larger level.” To attract the best talent, she said, “we need to address any hidden biases that systemically disadvantage one or more segments of the population. And since postdoctoral years are the early career years for geoscientists, women are potentially disadvantaged right from the beginning of their careers.”

Faculty members, scientists, policy makers, department chairs and administrators may want to hold workshops and discussions focused on awareness of implicit bias, Dutt suggested. Postdocs and graduate students planning to apply for positions also may also use the study to start such conversations, she added.