You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Each year brings news that the graduation rates for college athletes have a hit a new record high, with the National Collegiate Athletic Association making particular note that African-American athletes “dramatically outperform” their nonathlete peers.

But a new study from the University of South Carolina’s College Sport Research Institute suggests that football players at the NCAA’s five wealthiest athletic conferences are in fact struggling to keep up with the rest of the student body. And black football players are falling behind more than other male students.

“The numbers are striking,” said Mark Nagel, associate director of the College Sport Research Institute. “There’s a very large discrepancy between football players and other full-time male students on campus. Many football players are not prepared for the rigors of college, and they’re being asked to step up to the plate academically while also having to work full time playing football. Both demands are taking up so much time, effort and energy, and it really creates a bad situation for them.”

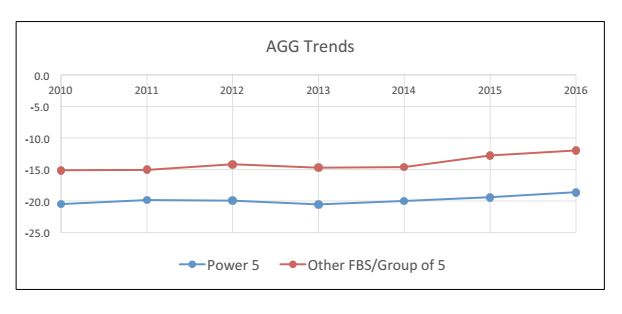

The study compares the six-year federal graduation rates of institutions in the five wealthiest leagues -- the Power Five, consisting of the Atlantic Coast, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-12 and Southeastern Conferences -- as well as the lower-tier Group of Five conferences. The researchers compared the rates of white and black football players to all full-time male students at their institutions.

Calling their measure the "adjusted graduation gap," the researchers excluded all part-time students, a group that is normally included in the federal graduation rate, as long as they are full time when they first enroll. Part-time students, the researchers said, graduate at lower rates than do full-time students, and all Division I NCAA athletes are required to be full-time students. (Many Division I athletes also receive substantial athletic scholarships that diminish the likelihood they will have to drop out of college for financial reasons, as meaningful numbers of students do.)

The researchers found that when comparing federal gradation rates of only full-time students, the graduation gap for black football players in the Power Five conferences was nearly five times larger than that of white players. White football players graduated at a rate five percentage points lower than other full-time students. Black players graduated at a rate 25.2 percentage points lower than other full-time black male students.

The gap was smaller at the Group of Five leagues, which includes Conference-USA and the American Athletic, Mid-American, Sun Belt and Mountain West Conferences. The difference in graduation gaps for black and white players was 13.1 percentage points.

The findings “were concerning,” the researchers, wrote, “given the increasing economic exploitation of NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision players.”

The National Collegiate Athletic Association has noted that the federal graduation rate used in the study does not account for students who transfer. When the NCAA's metric, the graduation success rate, is used, graduation rates for all athletes are much higher, as it excludes athletes who have transferred or otherwise left in good academic standing -- though not necessarily graduated. It also excludes athletes who have transferred into a program. "There is no evidence that any part-time bias exists in graduation rates," the NCAA has stated, "and this approach does not account for the wide variety of campuses and types of students at those campuses."

The association frequently touts in commercials and on its website that African-American college athletes outperform their nonathlete peers, according to the federal graduation rate. This includes part-time students.

“The graduation success rate and unadjusted federal graduation rate don’t allow for that apples-to-apples comparison that our study does,” Nagel said. “We always just say it’s a different metric, and that it tells a different story -- one is not necessarily better or worse.”

The new report joins other research that suggests black athletes in the top NCAA athletic conferences may not be receiving the education they were promised.

According to a study published in March by the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education, just over half of black male athletes at the 65 wealthiest athletics programs graduate within six years, compared to 68 percent of athletes over all and 75 percent of undergraduates over all. The gaps were comparable to when the center conducted a similar study in 2012.

The study compared the federal graduation rates of black male college athletes, all athletes, black male undergraduates and all undergraduates at Power Five colleges and universities. Two-thirds of those institutions graduated black male athletes at rates lower than black men who were not athletes. Just one institution -- Northwestern University -- graduated black male athletes at a rate higher than or equal to undergraduate students over all.

Shaun Harper, executive director of the Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education, said it’s time for the NCAA and colleges to better acknowledge the academic struggles of black male athletes, in particular those in revenue sports like football and basketball.

“Athletic departments have to be held accountable for ensuring they are bringing in people who are college ready and who are not just there to play football and basketball, and if you’re going to bring in people who are not academically prepared, the least you can do is get them the support they need,” Harper said. “The NCAA and athletics departments like to say, ‘We have all these student-athlete services and we have very sophisticated operations for helping athletes academically.’ But the data continue to tell us that those services are not good enough. You have to do more.”