You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

Being a department chair can feel like running a small business, yet most professors aren’t trained for that kind of work. Initial data from a new study of department chairs suggest that most don’t even receive training for their role. Moreover, when professors do receive training to be chairs, advice centers on hard skills that may or may not be relevant rather than on interpersonal and other soft skills that can make or break a departmental climate.

“It’s more ‘how to do a budget sheet’ or ‘where do budgets come from,’ as opposed to how to cut a budget,” said Kelly Ward, the study’s co-lead and chair of educational leadership, sports studies and educational and counseling psychology at Washington State University. “It’s ‘here’s the annual review process,’ as opposed to do ‘How do I deal with someone who’s not performing?’”

Ward said the lack of both initial and ongoing development for chairs is unfortunate and shortsighted, since good chairs contribute to faculty satisfaction and retention throughout the department, and because department chair is an important pathway to other administrative jobs. So if institutions want to attract strong leaders from diverse backgrounds, she said, it’s wise to help them succeed in what is often their first real leadership role.

The study was funded by the University Council for Educational Administration; Ward directs its Center for the Study of Academic Leadership. She and colleagues explored department chairs’ roles, responsibilities, stresses, job satisfaction and career trajectory, in part to compare those findings to a similar study of chairs conducted in 1991. Respondents represented all kinds of institutions and disciplines.

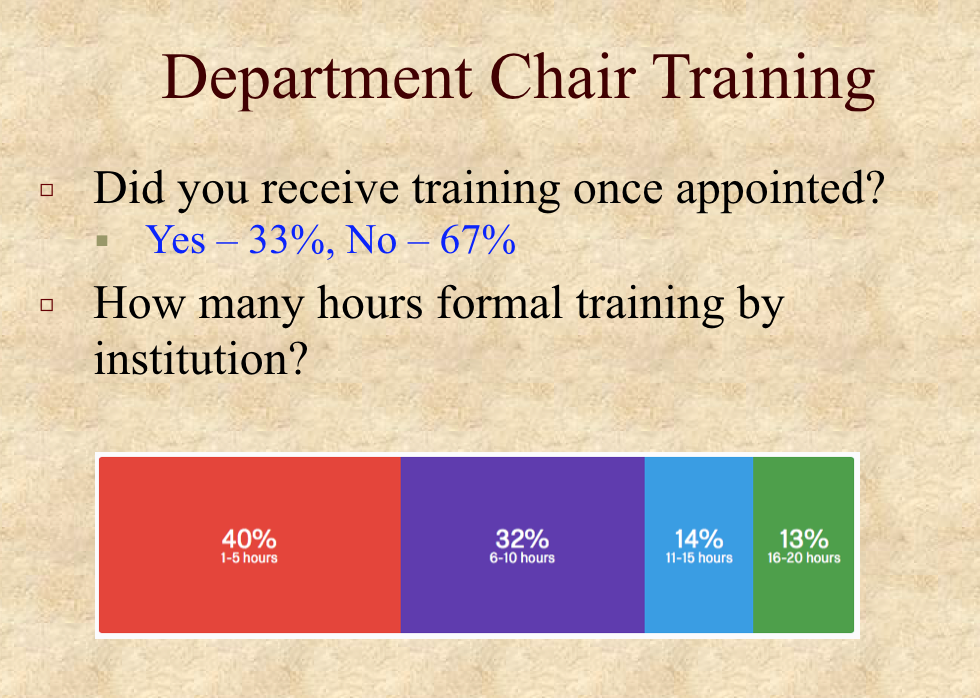

The average term as chair is about four years, according to the new study. Yet 67 percent of chairs receive no formal training from their institutions. Most of those who do receive training get 10 hours or fewer.

Source: UCEA/Kelly Ward

Perhaps worst of all, two-thirds of those who have received training say it didn’t adequately prepare them for the job. Top five topics covered in training are resource allocation and budgeting, legal issues, promotion and tenure, advancing diversity, and conflict management.

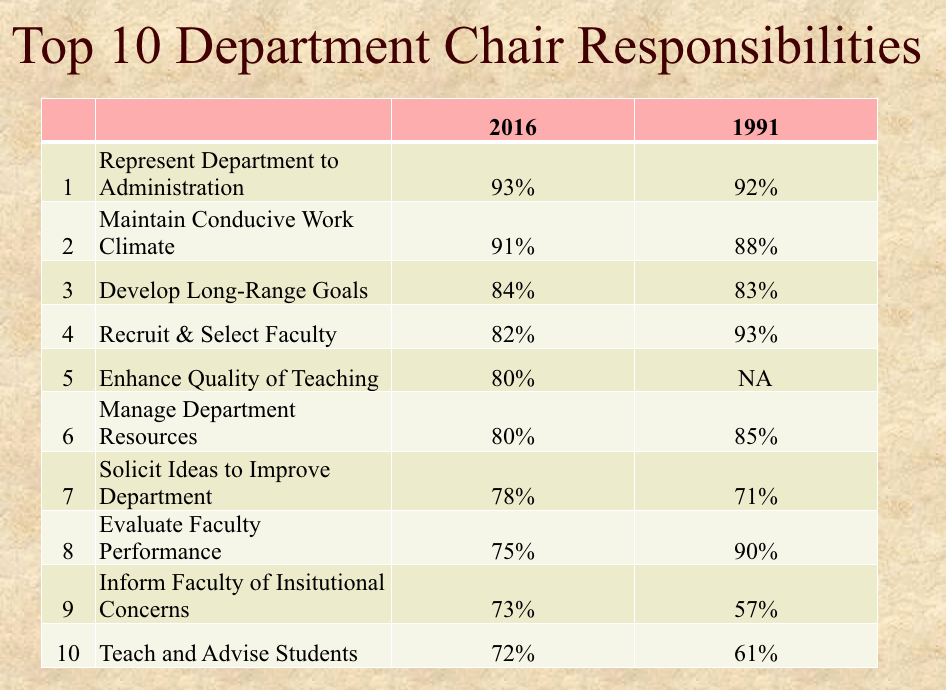

Some job duties that require more training, according to respondents, are evaluation of faculty performance, maintaining a healthy work climate, obtaining and managing external funds, preparing and proposing budgets, and developing long-range goals.

Chairs eventually learn about those topics, presumably on their own, though, as the mean response to a question about how competent chairs feel is about four, on a scale of one to five. Most respondents say it took them between six and 18 months to feel that way.

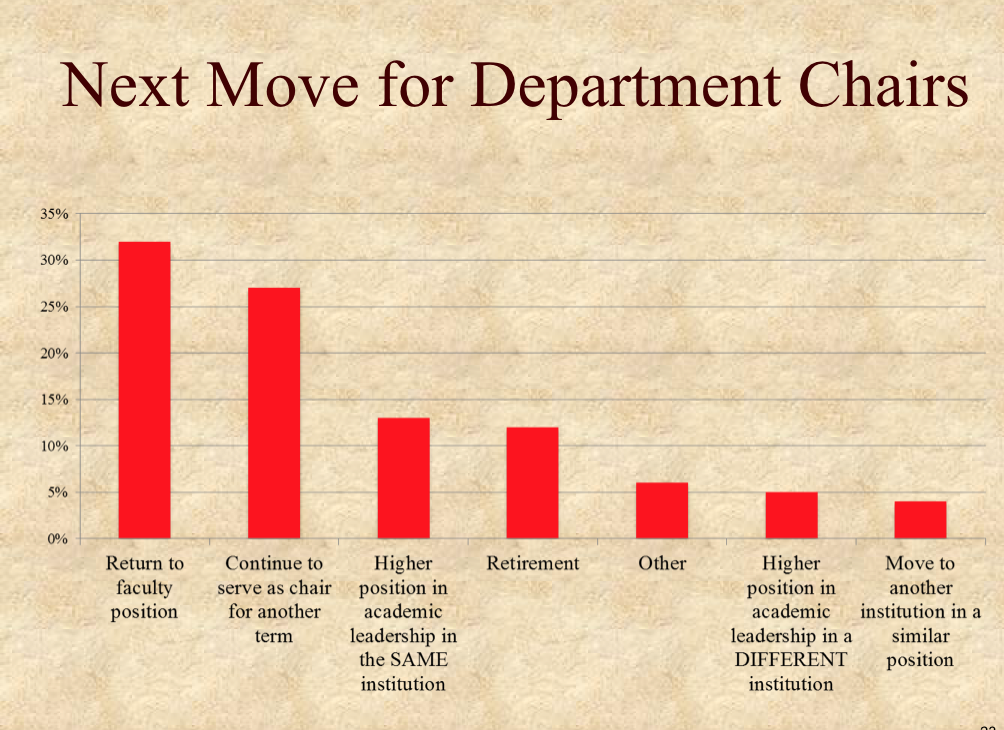

Despite the adjustment period, 89 percent of chairs say they would do the job again -- what Ward called a “happy” finding. Few have plans to move up in the administrative ranks, however.

More training, previous experience in leadership roles, peer support and networking all would help chairs feel more competent. So would mentoring from deans or other academic leaders and department chairs, as well as actual job descriptions and clear policies and procedures. About half of chairs said they “sometimes” network with other chairs on operational, professional and strategic issues.

The day-to-day responsibilities of a chair haven’t changed all that much since 1991.

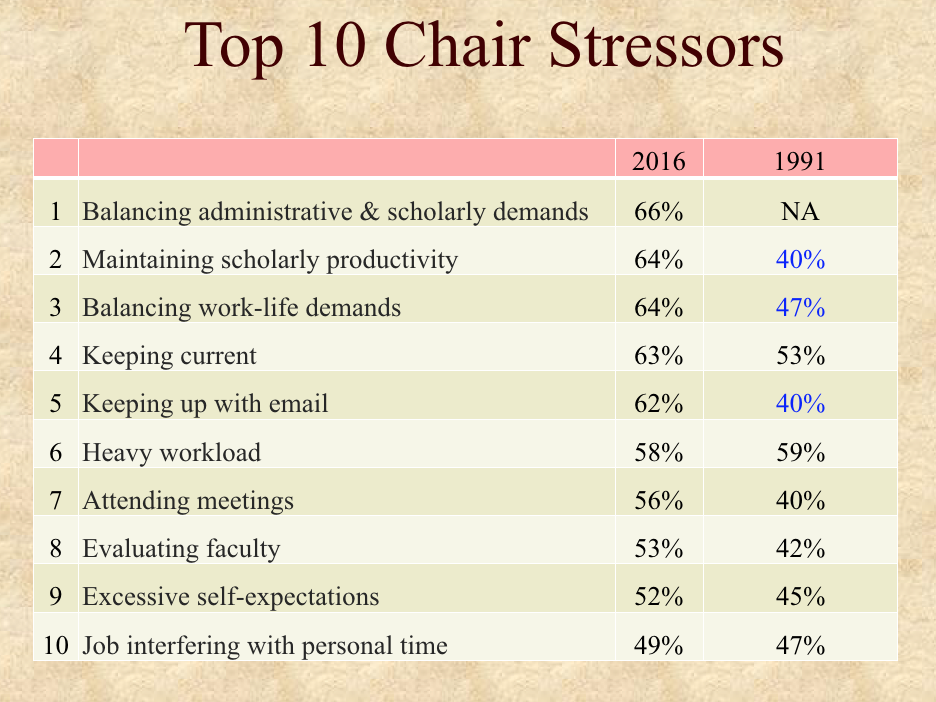

Yet the stressors are different, including balancing work-life demands and keeping up with email. Ward said the data require further study but suggest that chairs today are doing more work over all than their counterparts of years past. That’s probably, in part, because many departments are much bigger than they used to be, including those that have combined multiple disciplines. The job of a chair these days is similar to that of dean in many cases, she added, noting that she oversees 44 people and five programs.

Chairs’ top challenges today are dealing with time pressures and resource restrictions, and managing work-life balance.

Similar reasons drove faculty chairs to take on the role now and in 1991, including personal development, necessity and a sense of duty. Many chairs today also say they took on the job to advance the department.

Compared to the earlier study, a small proportion of chairs -- just 27 percent -- consider themselves academic faculty members only. Some 70 percent of chairs now say they're part of both the faculty and the administration, compared to about half of respondents in 1991.

Other researchers involved in the new study were Walter Gmelch, professor of leadership studies at the University of San Francisco, co-director of the academic leadership center and a longtime expert on faculty chairs (he published the 1991 study), and two graduate students at San Francisco, Drew Roberts and Sally Hirsch.

Surveys were sent out to a national sample of chairs at various institution types, from research universities to community colleges, within multiple disciplines. The response rate was about 34 percent, or 336 surveys. Two-thirds came from private institutions, and most were from campuses without faculty unions.

About 60 percent of respondents are full professors, down significantly from the 1991 survey, in which about 80 percent of chairs were full professors. About one-quarter of recent respondents are associate professors. About 45 percent of respondents are male, compared to roughly 90 percent in 1991, suggesting significant gains in gender diversity among chairs over time.

Some 85 percent identify as white, 4 percent as Hispanic, 3 percent as black and 3 percent as Asian or Pacific Islander. While chairs are still overwhelmingly white, they are more diverse as a group than in 1991.

Just 81 percent had tenure when they were appointed chair, compared to 93 percent in 1991.

Most chairs are between 46 and 55 years old. Most are married and about half have children at home. Twenty percent care for elders.

Sherri Hughes, director of leadership at the American Council on Education, said Ward’s findings align with what she hears and sees leading the council’s Leadership Academy for Department Chairs.

“When I talk to chairs and ask about training at their institutions, what I find is that it tends to be the ‘nuts and bolts’ -- ‘here’s how to use this system,’ ‘here’s how to file these reports by these deadlines.’ But the really important things they’re struggling with are the interpersonal dynamics … facilitating conversations and getting people to have a common vision.”

Hughes added, “Many institutions don’t quite know what to do about training. Some will have formal or informal mentoring for new chairs, but that’s still essentially learning on the job -- somebody you can call when you’re freaking out.”

Can soft skills be taught? Hughes said yes -- they’re the focus of her workshops. Rather than spotlighting departmental minutiae, Hughes said she tries to take a cross-disciplinary, cross-institution approach, talking about how to deal with conflict and give effective feedback. Sometimes chairs are reluctant to lead colleagues because they know they’ll eventually return to the faculty and face possible retribution for the decisions they've made or things they've said, but being among a network of chairs at the workshop who are in similar situations can help everyone feel more comfortable, she said.

Who should provide training? Ward said it must be considered a key task of an administrator who oversees the faculty -- as important a task as development, mentoring and support for new faculty members.

“One law that we know about faculty life is that it’s made or broken by a good chair,” she said. “If we want to have a quality and diverse faculty, then we have to have good department chairs. So many times, when people run off [the job], it’s because of what’s happening in their unit.”