You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

Language education is dwindling at every level, from K-12 to postsecondary, and a diminishing share of U.S. residents speak languages other than English, according to a new report from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. “The State of Languages in the U.S.: A Statistical Portrait” is a precursor to another forthcoming report from the academy about how the U.S. might build language capacity to meet the needs of the increasingly global economy and otherwise “shrinking world.”

“While English continues to be the lingua franca for world trade and diplomacy, there is an emerging consensus among leaders in business and politics, teachers, scientists, and community members that proficiency in English is not sufficient to meet the nation’s needs,” the new report says.

John Tessitore, senior program adviser at the academy, helped compile the statistical portrait based on existing data on second-language learners and speakers in the U.S. for the academy’s Commission on Language Learning. He said the commission believes that foreign language should be of a higher priority throughout the American education system -- not at odds or competing with other priorities, such as science and math, but alongside them.

“This is about increasing access and making language learning available,” he said. “Every student should have access and should be able to learn a language over the course of their educational life, whether they go to college or not.”

National Snapshot

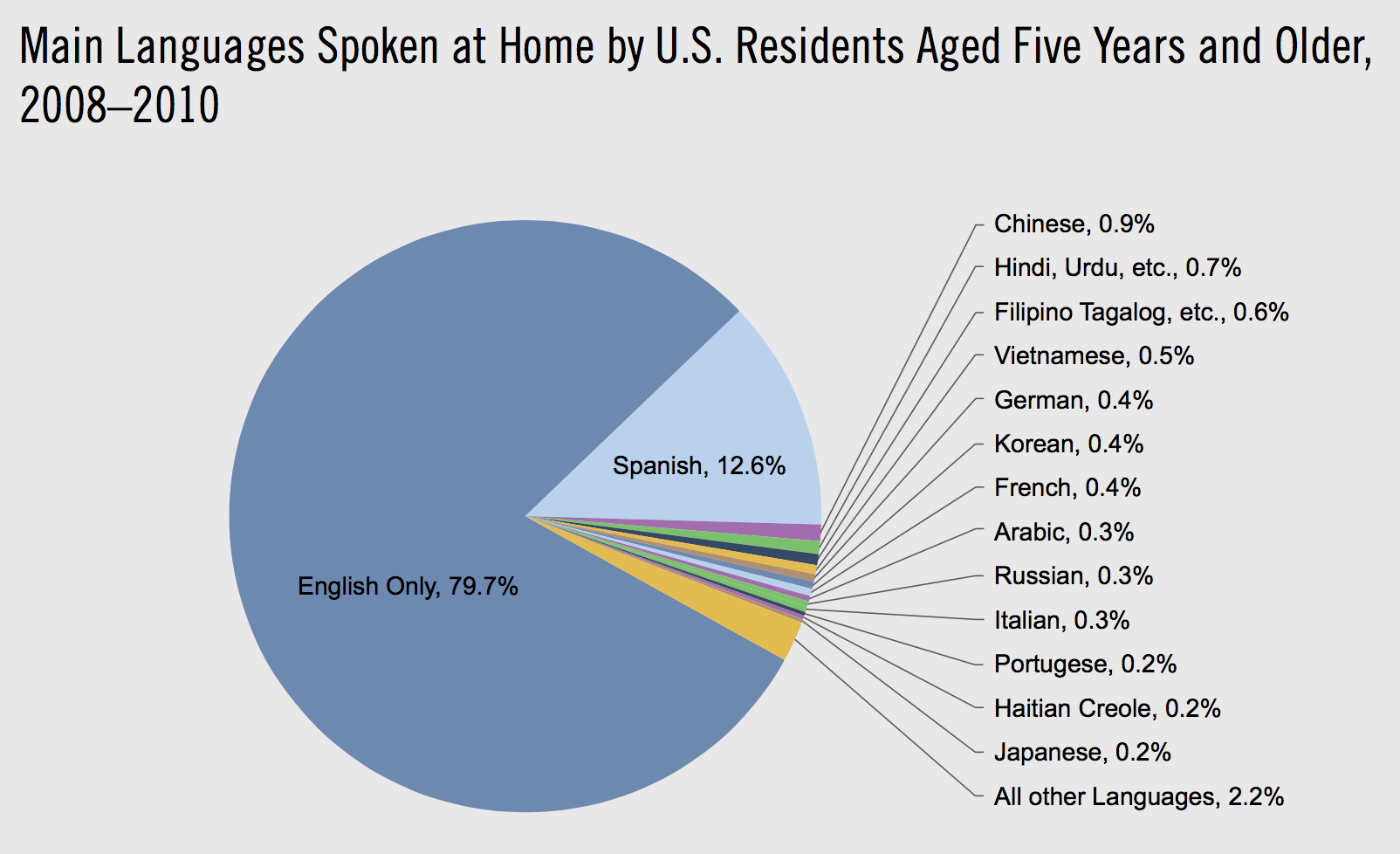

According to U.S. Census Bureau data included in the report, more than 60 million residents over age 5 -- or about 20 percent of the population -- speak a language other than English at home. But other research suggests that just 10 percent of the population speaks a second language proficiently, and most are "heritage speakers," the report says. Of those who speak a language other than English at home, 57 percent were foreign born.

Nearly two-thirds of foreign language speakers speak Spanish, but the remaining one-third represent incredible linguistic diversity -- some 350 languages, according to the report. Those include 169 Native American and indigenous Alaskan languages, which are listed as vulnerable or critically endangered by UNESCO. A number of projects are dedicated to their revival.

The Modern Language Association and other groups have highlighted the need for providing more opportunities for heritage language learners, and one study included in the new report demonstrates why. The study, in Southern California, found that even in an era with a very high percentage of non-English speakers, language proficiency declines precipitously with each generation. More than 45 percent of immigrants who arrived before age 13 were able to speak and understand a non-English language well, even if they weren’t literate in it. But by the third generation, fewer than one in 10 were able to communicate well in their heritage languages.

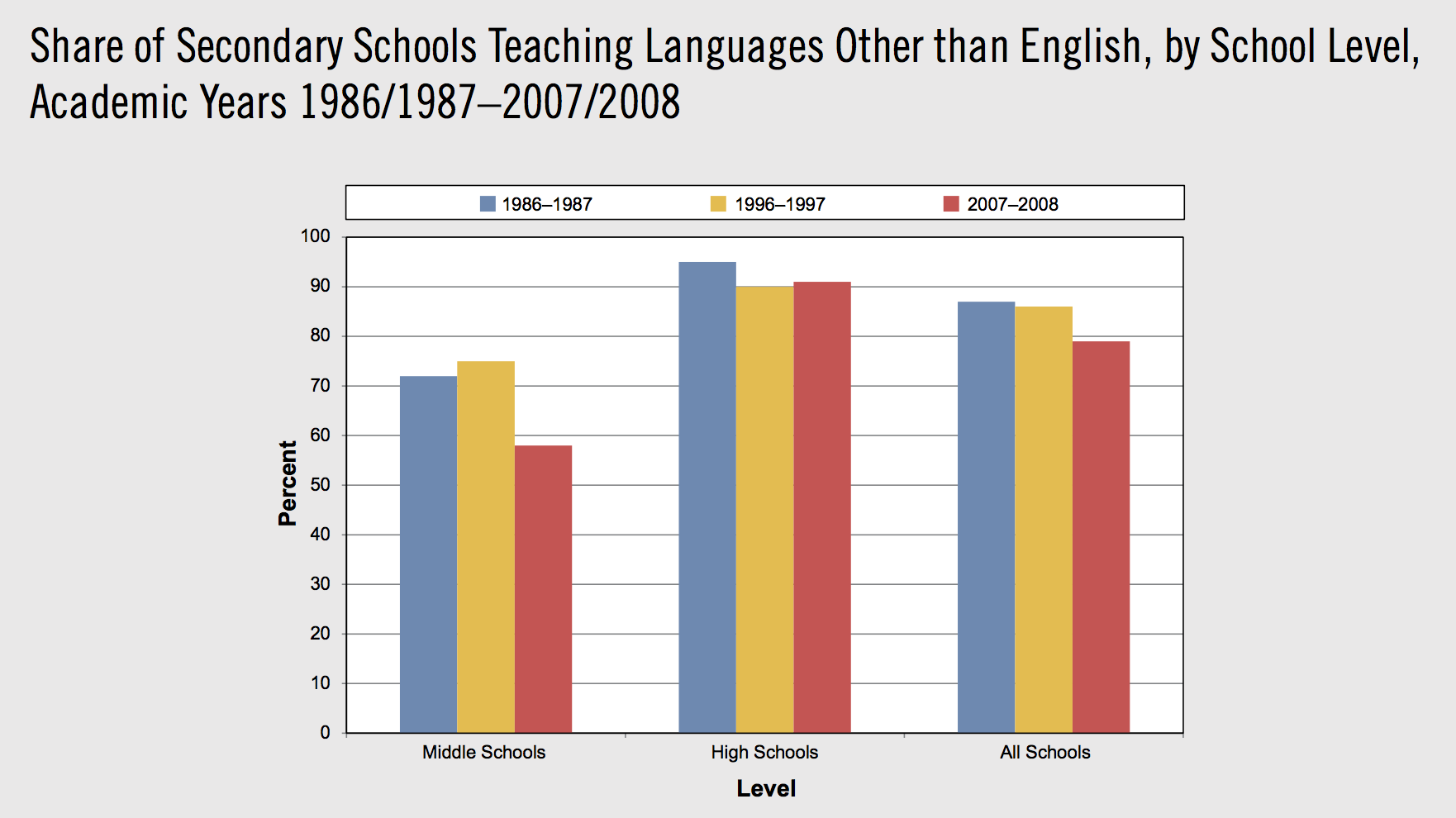

Early exposure is best when it comes to language learning, most experts say, yet fewer and fewer elementary schools, especially public ones, offer such opportunities. In 2008, 25 percent of all elementary schools taught languages other than English, a six-point decline from about a decade earlier. Middle school offerings also have decreased, and only a small minority of high school students are taking intermediate or advanced language courses, where proficiency begins to form, according to the report.

Elementary and secondary school language enrollments also vary by region, with the highest density in the Northeast. Nationwide, 22 percent of elementary and secondary school students are enrolled in language classes or programs. Dual-language immersion courses are even more rare but offer real benefits, according to a recent study included in the commission’s report. By the time dual-immersion students reached the fifth grade, they were an average of seven months ahead in English reading skills compared with their peers in nonimmersion classrooms. By the eighth grade, students were a full academic year ahead.

Regarding instruction, the number of public high school teachers specializing in world languages has not changed substantially over the most recent decade for which data are available, even though there is a well-documented teacher shortage. “The one exception is Spanish teachers, whose numbers increased by over 10,000 from 2004 to 2012,” the report says. “Unfortunately, over that same time period, the share of students in French, German, Latin and Spanish language classes who had a teacher with a college degree in the subject fell between 5 percent and 11 percent.”

Colleges and Universities

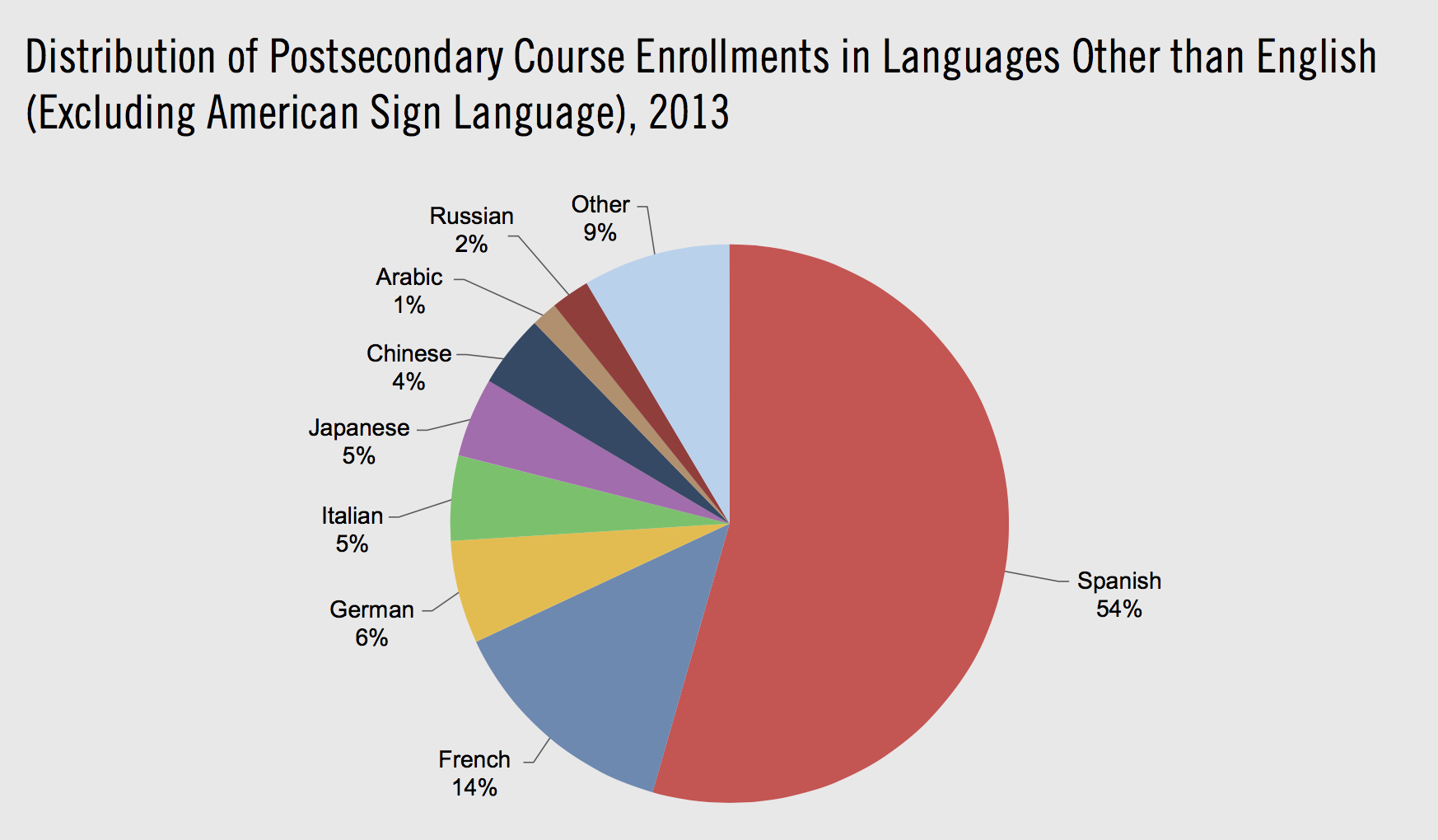

At the college and university level, Spanish is the most commonly studied world language, accounting for more than 54 percent of all student enrollments in 2013. Other European languages account for most of the other enrollments, but three of the 14 federally designated “critical need” languages are among the most popular: Japanese, Chinese and Russian.

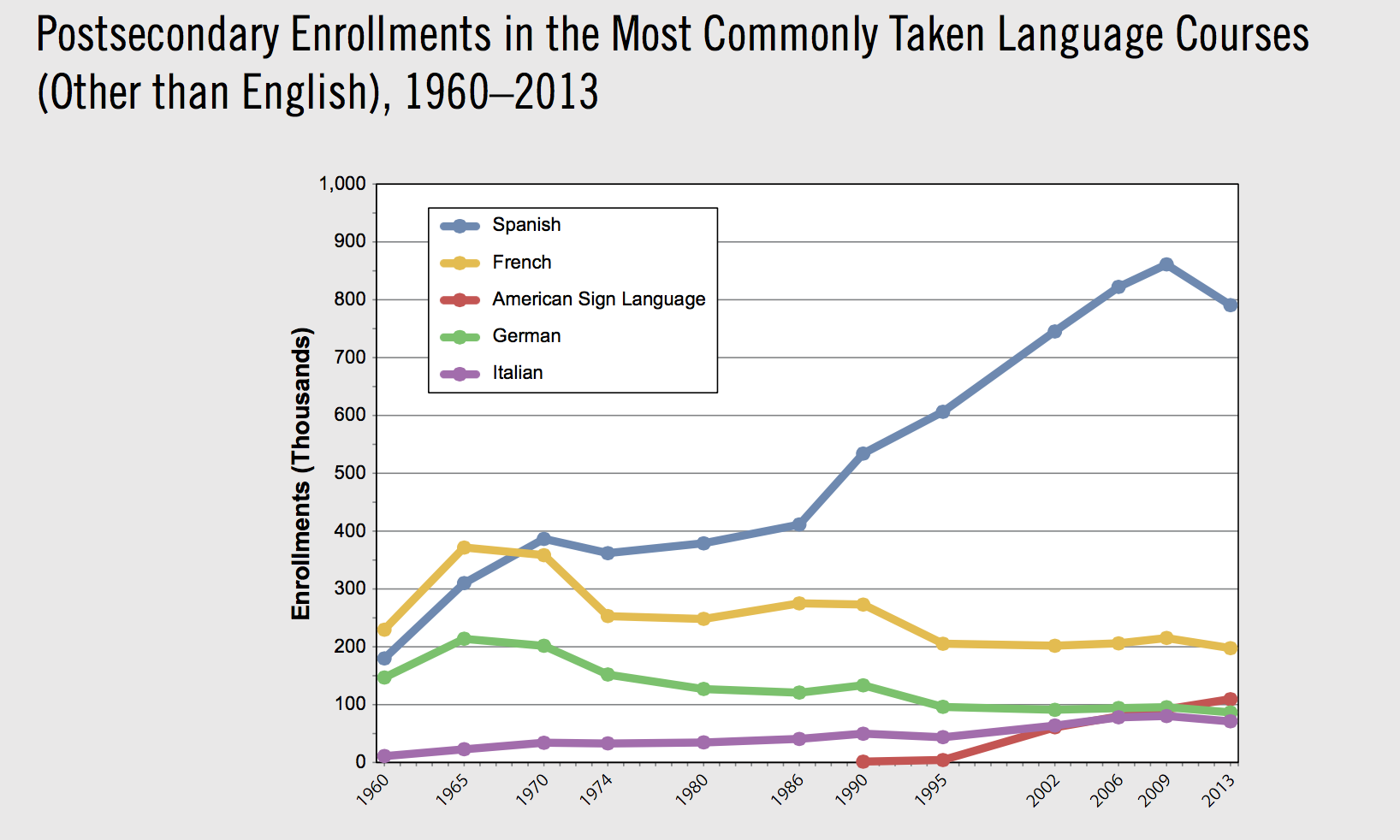

With the exception of American Sign Language, the number of students enrolled in the most commonly studied languages fell from 2009 to 2013, based on the most recent data from the MLA. Prior to 2009, enrollments in Spanish had grown dramatically since the mid-1980s, while the number of students enrolled in some of the other commonly studied languages had been trending lower, the report says. It notes that the sharp growth in the number of students taking Spanish since 1986 is “slightly deceptive,” however, since the total number of students enrolled in college also has increased over that period. So the ratio of modern language enrollments per 100 students has been rising and falling in a narrow range, from about eight to nine.

Undergraduate degrees conferred in modern languages also are on the decline since 2010. Over the longer term, the number of students earning degrees in European languages other than Spanish has fallen by one-third since the early 1990s, but the study of languages from Africa, Asia and the Middle East has grown since that time and remains above or near the number of degrees conferred in 2010.

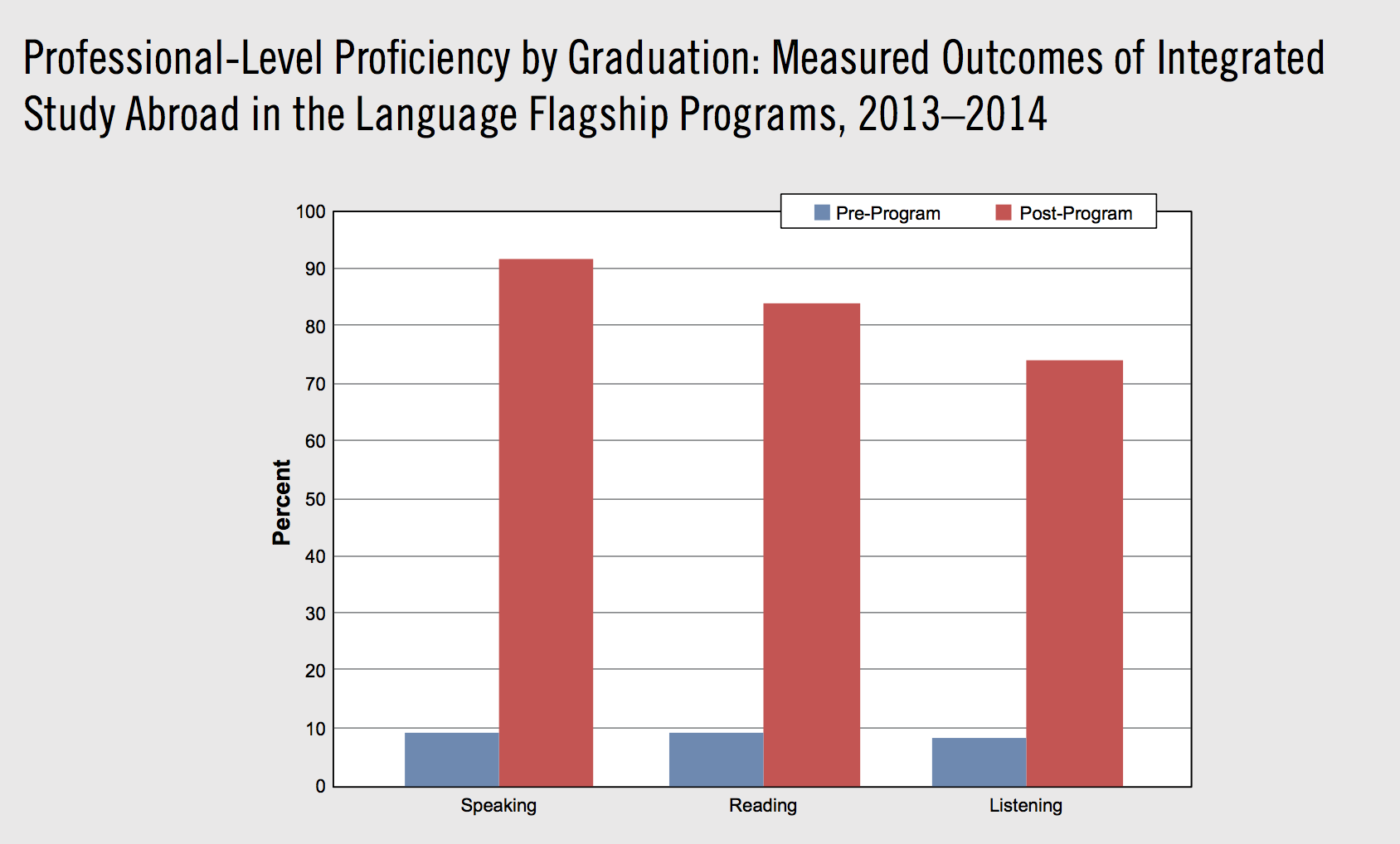

American students can attain advanced or professional levels of proficiency in a foreign language by the time they graduate from college by enrolling in standards-based language courses at their home university together with a year of integrated study abroad, the report says. Language Flagship, a national initiative aimed at graduating professionals fluent in critical languages, includes intensive domestic training and a capstone year abroad. The State Department's National Security Language Initiative for Youth and Critical Language Scholarship programs also support more than 1,000 students in overseas study of critical languages annually.

“The data indicate that most students can learn a language successfully, given proper instruction and adequate support,” reads the commission’s report.

The commission also highlights a handful of recent studies about state and local job markets’ need for bilingual employees. A study in Massachusetts, for example, found a sharp increase in online job postings seeking a candidate who could speak a language other than English, from 5,612 openings in 2010 to 14,561 in 2015.

The report ends with a series of questions that the data alone can’t answer, such as, how many of the people who report proficiency in a language other than English can use it effectively in personal and professional communications? How many heritage students develop proficiency in their heritage languages in addition to English? How does a lack of language requirements, both at the K-12 and the university and college levels, impact language acquisition in the U.S.? And what is the impact of language acquisition, or lack thereof, on career success and business, diplomatic or other opportunities?

The forthcoming report, expected in February, will explore some of these questions and suggest ways to increase second-language capacity.

Rosemary Feal, executive director of the MLA, helped prepare both reports as a member of the commission. A major takeaway of the first, she said, is that "we have about 20 percent of people in this country who are basically bilingual or very fluent in another language, but virtually all of them are from heritage speaking backgrounds. So as a nation we are far behind other countries in having students acquire advanced language proficiency through education." Part of the problem is lack of opportunities for language study, particularly in public schools in the early grades.

At the same time, she added, there's an incredible number of languages spoken here -- a kind of untapped resource.

“If we as a nation would put those things together -- language diversity and language education opportunities -- we could really work toward the goal of having a larger percentage of U.S. residents fluent in more than one language.”

Feal said that the commission’s goals are dependent on support from the Education Department, Congress and other policy makers, and it’s unclear how the new administration will embrace language education, if at all. Yet Feal pointed out that future First Lady Melania Trump is multilingual and that her son, Barron Trump, is learning several foreign languages.

“I hope that Americans emulate that model,” she said.

Feal said it’s important that decision makers understand that while language study is an important aspect of the humanities, it’s also important for business. “We rarely stop and think when we’re talking about the need for students to prepare vocationally -- which there’s a big push toward in the current environment -- about language, and how it’s a hugely marketable skill in the business world, and many other worlds.”