You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

AHA

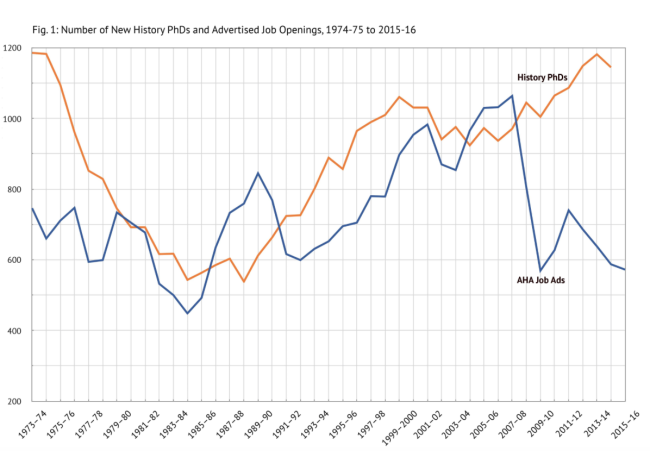

Available jobs for history Ph.D.s are down, but so is the number of new Ph.D. recipients, suggesting a slight market correction, according to information released Wednesday by the American Historical Association. The growth in job opportunities outside academe suggests that the association's continuing efforts to prepare historians for a diverse range of careers is seeing some success.

“The professorial job market remains flat, but there are new possibilities,” said Jim Grossman, executive director of the AHA. “We’re seeing that things aren’t going to get better in terms of tenure-track faculty jobs, but we’re also seeing that maybe we will be successful at increasing the presence of history Ph.D.s in more diverse sectors of the economy, and within academia itself, as well -- entry-level, administrative-type jobs and other professional jobs in higher ed, but not teaching.”

Since the recession, the number of jobs advertised with the AHA at careers.historians.org has “typically dropped while the applicant pool has grown,” reads AHA’s new report. “But the newest data on the academic job market in history signal a slightly different picture. In 2015-16, the number of ads once more edged down slightly, but the average number of applications for some jobs appeared to shrink as well.”

Last academic year, AHA received 571 job ads for full-time positions, including on and off the tenure track, fellowships, and nonacademic jobs. That amounts to a 2.6 percent drop in available jobs from the previous year, and marks the fourth straight year of decline.

But that dip was matched by a slight, 3.1 percent decrease in the number of new history degrees awarded in 2014-15, according to a new federal tabulation.

Still, the number of new history doctorates was the second largest in 40 years, at 1,145.

The largest number of history Ph.D.s (413) went to North America specialists, as usual, but they continued to make up a smaller share of degrees awarded (from 40 percent several years ago to 36 percent in 2014-15). European history degrees conferred also declined over the same period, from 224 in 2010-11 to 198.

By contrast, Ph.D.s earned by Africa, Asia, Latin America and Middle East specialists also have increased in the last five years. Asian history degrees conferred grew from 68 to 89.

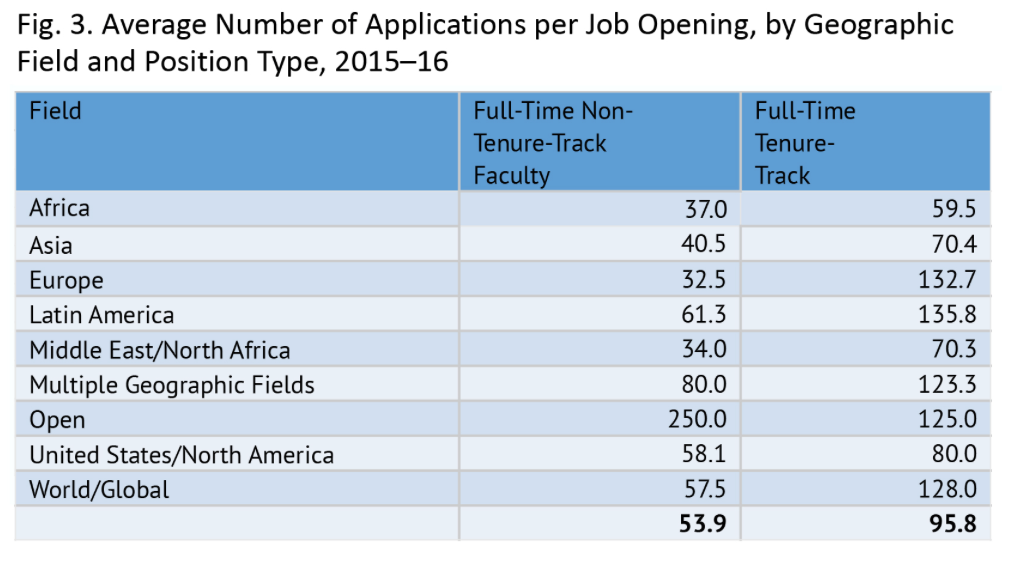

The largest number of job openings was in U.S. history, with 150 of 572 total ads, up from 128 the year prior. European history jobs, meanwhile, fell substantially, from 87 openings in 2014-15 to 66 last year. The number of Asian and Latin American history jobs fell, too, but by a much smaller number.

The number of academic jobs with a primary focus on topical specialty or skills also fell year over year, especially for those in histories of religion and diplomacy -- by 71 percent and 67 percent, respectively. Perhaps surprisingly, ads listing digital history as the primary job requirement also fell 47 percent, from 15 to eight. At the same time, more ads -- 12 percent over all -- mentioned those skills as desirable.

Looking outside the professoriate, job ads in public history and nonteaching positions in academe were up significantly, year over year -- from 14 to 66. That figure rivals the number of academic listings in some subfields, according to the report.

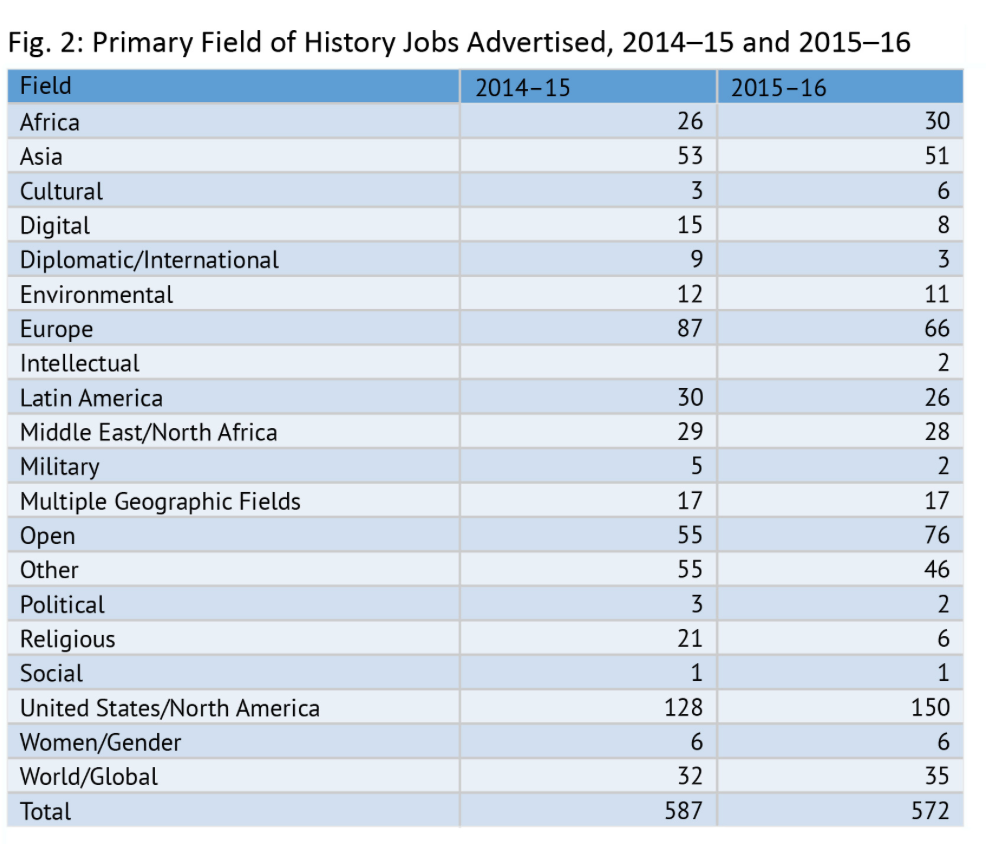

AHA notes that it’s impossible to know how many Ph.D.s who earned their degrees prior to 2015 may have applied to last year’s open jobs from the numbers alone. So to measure competition for positions, it sent a follow-up survey to all 572 of last year’s advertisers, asking for basic information about applicants. Results from 231 respondents suggest “heavy competition,” to the tune of about 82 applicants per position, and 96 applications per tenure-track opening, in particular.

African history tenure-track positions received the smallest number of average applications, at about 60 per opening. That’s compared to 136 for openings in Latin American history or 133 for European history.

“A handful of respondents for the European history positions offered particularly grim assessments of the academic job market, with one noting, ‘Nothing broke my heart more than the initial vetting of application files,’” reads the report. “We received nearly 300 files, and the vast majority were from well-qualified people. I cannot imagine how disheartening it must be for young scholars vying for a tenure-track position in the present market.”

Curiously, the report says, entry-level job openings focused on U.S. and North American history received a relatively small average number of applications, at 80 per full-time tenure-track opening. That’s a substantial drop from the previous survey, concerning 2010-11 job ads, when there were about 100 applications for every entry-level U.S. history job.

At the same time, the average number of applications for U.S. history specialists in nonteaching positions advertised with AHA had larger pools of candidates, at about 113 candidates each.

Nine percent of the new faculty hires had not yet earned a Ph.D. About 11 percent had earned their degrees more than five years earlier. “This share has been trending upward in the 20 years of advertiser surveys,” reads the report. “Two decades ago, just 5 percent of the new hires at this level were more than five years from their doctorates.”

Taken as a whole, it continues, “the data point to continuing challenges for recent Ph.D.s seeking academic appointments, with dozens of applicants competing for every entry-level job and unpredictable fluctuations in field-specific openings from year to year. Whether the 2015-16 AHA data herald the beginning of a new trend will only become clear in years to come.”

Grossman remained hopeful that nonteaching job ads would continue to increase, and the AHA is taking pains to both raise awareness among employers of all stripes about the advantages of hiring history Ph.D.s and prepare historians for a variety of jobs. It recently won $1.5 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to expand its Career Diversity for Historians initiative beyond four pilot campuses, for example. AHA is also expanding its data-gathering efforts to create a single-online database of career outcomes for all historians awarded Ph.D.s from 2003 to 2014.

“The problem is that right now people have to be extraordinary to blaze these paths for themselves,” he said, noting that similar preparation is needed for jobs both inside and outside academe. “We want to make it a normal set of possibilities.”