You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

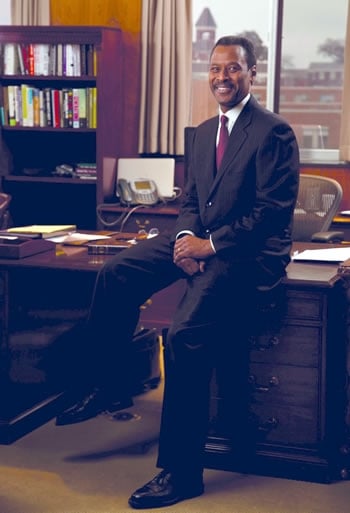

President John Silvanus Wilson Jr.

Morehouse College

Tuesday came and went with little in the way of additional explanation for why Morehouse College’s Board of Trustees decided not to renew President John Silvanus Wilson Jr.’s contract, setting up the end of his tenure after four short years.

The board of the all-male historically black college in Atlanta decided over the weekend not to renew the contract of Wilson, who arrived on campus to lead his alma mater in January 2013 after serving as the executive director of the White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities since 2009. Wilson will step down in June when his current contract ends.

Many were unsurprised by the decision. The president had already seen his original three-and-a-half-year contract extended by a single year. If he was to get a new, longer contract at Morehouse, it likely would have been inked this fall.

Further, Wilson has endured his share of bumps during his tenure. He put budget cuts in place to stem a financial crisis in 2013. He took criticism for being unable to reverse a recent history of falling enrollment at Morehouse. And he found himself the target of alumni and other critics, some of whom circulated a well-publicized petition in October calling for his ouster while listing alleged grievances including limited transparency, continual financial issues and turnover among faculty and staff. The idea that Morehouse was tight on money and struggled to land students might shock some in higher education, who see the institution as a prestigious black college with a storied history and far more resources than many other HBCUs.

Wilson’s departure was far from universally lauded. Students and faculty members took issue with the way trustees reached their decision, objecting to the fact that student and faculty trustees were shut out of the decision-making process. Meanwhile, those who watch historically black colleges voiced concern that Wilson’s firing is a reflection of the uniquely high pressures that contribute to high turnover among the ranks of HBCU leaders.

Wilson, for his part, declined to go into detail on the circumstances that led to his departure.

“I’ve been in higher education my entire career, and I understand very clearly that every president serves at the will of the board, and sometimes you get a clear and immediate explanation, and sometimes you don’t,” Wilson said in an interview Tuesday. “I think the question about why this is happening is more appropriately posed to the board.”

The chairman of Morehouse’s Board of Trustees, Robert C. Davidson Jr., did not respond to a request for interview. He did not address the reason for Wilson’s departure in a press release, instead saying in a statement that Wilson “turned around Morehouse” in several ways.

“He and his team were champions for STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts and math) initiatives for our students and significantly increased the college’s private gifts, grants and contracts,” Davidson said in a statement. “In addition, Dr. Wilson played a pivotal role in bringing President Barack Obama to Morehouse as the commencement speaker in 2013, and hosting Vice President Biden in 2015.”

Wilson listed other accomplishments during Tuesday’s interview: putting in place cost-containment measures shortly after he arrived on campus to improve Morehouse’s financial health, reorganizing the institution’s faculty and trying to improve the undergraduate experience. He’s proud that Morehouse’s four-year graduation rate improved by four percentage points since he arrived, he said. An improved graduation rate was one of numerous measures of success under a strategic plan Wilson put in place. The plan called for improving the graduation rate from 34 percent to 38 percent, with a stretch goal of hitting 45 percent or more.

Wilson also pointed to fund-raising as an area of success. Before his arrival, Morehouse generated between $10 million and $11 million per year in gifts, grants and contracts, he said. Morehouse raised $68.8 million during his four-year tenure, a college record, according to a spokeswoman.

The financial record is particularly important, Wilson said. He noted that Morehouse is a “niche institution” serving a small and relatively challenged subset of the student population.

“You have to speak in terms of financial strength first, because small liberal arts colleges are all challenged to make ends meet every year,” Wilson said.

The financial changes had a real impact, of course. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution noted that Wilson oversaw a $2.5 million cut to Morehouse’s operating budget in 2013, eliminating or downgrading 75 jobs.

Morehouse also drew criticism this fall over a decision to require students to live on campus for at least three years. Students had previously only been required to live on campus as freshmen. The decision meant $13,000 in mandatory room and board fees for every sophomore and junior on top of the college’s tuition, quoted at $26,700 per year. Administrators at the time said the move was not aimed at finances but was intended to increase student engagement.

Nonetheless, the on-campus requirement was received harshly in a petition calling on Morehouse to “purge” Wilson and members of his senior team. The petition said alumni have felt disconnected since Wilson started at Morehouse. It also criticized the college’s enrollment numbers, rankings, fund-raising performance, programmatic changes and staff and faculty turnover.

“The voice of the campus is not considered in affairs,” the petition reads in part. “In the same vein, President Wilson single-handedly has executed the largest turnover and restructuring ever in Morehouse history of employees in the admissions and the recruitment departments.”

Enrollment has fallen at Morehouse dating back before Wilson’s tenure. It fell from 2,900 in 2007 to 2,200 in 2014, he told the Journal-Constitution. Federal data listed undergraduate enrollment at 2,167 in the fall of 2015, the most recent data available.

Wilson said he took the petition’s concerns seriously. But he said alumni giving is up under his tenure. And he pointed out that the petition had less than 400 signatures, compared to thousands of Morehouse alumni. The petition’s goal was 500 signatures.

There is reason to question Morehouse’s financial outlook. Moody’s Investors Service in August downgraded a series of the college’s revenue bonds to Ba1, dropping its debt from investment grade to a high level of noninvestment grade and assigning it a negative outlook. Moody’s cited expected weak revenue growth, limited financial flexibility and a competitive student market.

The ratings agency did, however, note that Morehouse was revising its business model to rely more heavily on philanthropy and that it has “some demonstrated history of fund-raising prowess.” The college also received a significant pledge on Jan. 12, when Newell Brands Inc. committed $1 million for science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

Students, meanwhile, voiced displeasure with the way the Board of Trustees went about deciding not to renew Wilson’s contract. Student trustees were not allowed to take part in a Friday meeting that decided Wilson’s fate.

Three students filed suit over the matter in Fulton County Superior Court against Davidson, the Board of Trustees chair. Those students, Student Government Association President Johnathan Hill, student trustee Johntavis Williams and student trustee Moses Washington, have also been active in discussing their concerns.

The court action is still pending, according to Washington, a sophomore political science major.

“Our problem, and all the students’ problem right now, is that we were not afforded the opportunity to say whether we were in favor of Wilson or not,” Washington said. “We’re here 24-7. When the Board of Trustees leaves, you have to realize who’s at the school. You have the students. You have the faculty.”

The students also filed an online petition of their own saying that student trustees should advocate for and protect the best interests of Morehouse, regardless of students’ individual feelings on Wilson’s leadership.

Faculty members voiced their own complaints, with Faculty Council Chair Derrick Bryan issuing a statement. Bryan is an associate professor who chairs Morehouse's department of sociology.

"We, the faculty of Morehouse College, strongly object to the decision by the Board of Trustees not to renew the contract of President John S. Wilson without explanation and without the inclusion of faculty and student trustees in the discussion and decision," the statement said. "The faculty also expresses concern regarding the timing of the board’s decision. We demand an explanation and will investigate these decisions."

Morehouse’s leadership change comes at a time of competition for prestige, students and money -- both for historically black colleges and within Georgia and Atlanta. Nearby Spelman College, a historically black four-year women’s institution in Atlanta, has done extremely well in rankings. Meanwhile, the Georgia economy is booming, but many different colleges and universities are fighting for fund-raising dollars.

Susanna L. Baxter can shed light on the situation by describing the view from her Atlanta office. Baxter, the president of the Georgia Independent College Association, can see Coca-Cola’s operations and Georgia Tech -- a company that provides charitable dollars and a higher education institution that competes for them.

“I don’t envy the pressure that college presidents here have,” said Baxter, who declined to speak about any of her member institutions but addressed the climate in Georgia generally. “The competition is fierce, and the publics are having to raise more and more money.”

Experts, meanwhile, noted that Wilson’s predecessor, Robert M. Franklin, only served five years as Morehouse president from 2007 to 2012. Turnover is higher among HBCU presidents, they said.

A lack of funding relative to other institutions puts more pressure on presidential leadership at HBCUs, said Robert T. Palmer, interim chair and associate professor in the department of educational leadership and policy studies at Howard University’s School of Education.

“There is extra pressure to fund-raise,” Palmer said. “There is extra pressure to really focus on policies and show that students are learning what they are supposed to learn, and to be transparent.”

Marybeth Gasman, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and the director of the Penn Center for Minority Serving Institutions, said in an email that she was disappointed in the Morehouse board. Wilson had considerable issues to overcome and made tough decisions regarding funding, infrastructure, staffing and debt, she wrote.

More broadly, she sees the quick turnover at Morehouse as reflecting a larger reality at many HBCUs. Board should be supporting presidents and avoid being swayed by the loudest, most disgruntled alumni, she wrote. But often, that’s not what happens.

“Rather than do its job of setting larger institutional policy, raising money and promoting the college, Boards of Trustees spend too much time micromanaging and second-guessing the president,” Gasman wrote. “There are currently 17 vacancies at the 105 HBCUs, and this is not a good time for a lack of leadership -- especially at Morehouse, which is absolutely fundamental to the long-terms success of black men.”

Morehouse is well known as the college Martin Luther King Jr. attended for his undergraduate degree. Some noted that the release announcing Wilson’s pending departure was issued on Jan. 15 -- King’s birthday.