You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Temple University's Sport Industry Research Center

NASHVILLE, Tenn. -- College athletic programs and their fans are known to grumble that they are treated unfairly by the National Collegiate Athletic Association during its infractions process. Some in the largest programs complain they are treated more harshly than smaller teams. At the same time, smaller programs sometimes gripe that the lucrative big-time teams are the ones that get off easy.

A new independent study presented here Thursday at the NCAA’s annual meeting challenges both assertions: researchers at Temple University found that NCAA conference membership has little to no effect on the severity of penalties issued when colleges are found responsible for violating association rules. The study comes at a time of increased focus on NCAA infraction cases and the process behind the association’s decisions. In 2016, the NCAA Committee on Infractions issued a record number of decisions -- 32 cases in total -- for Division I. The previous record was 23 cases in 1986.

“I come from an institution that had a major case a few years ago,” Dave Roberts, vice president of athletic compliance at the University of Southern California, said, referring to a high-profile case involving the amateur statuses of two star athletes that resulted in some of the harshest penalties ever issued by the NCAA. “There was a big outcry in the local media and on campus, and it was really part of a clarion call across the country questioning the consistency, the transparency of some of the infractions decisions. I think [this study] is going to show you that, in large part, the data is actually very, very consistent.”

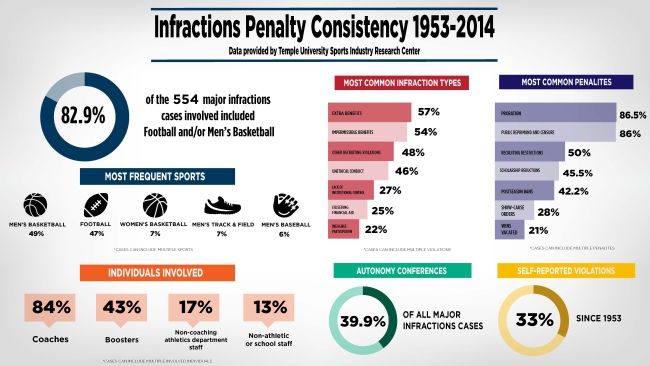

Researchers at Temple’s Sport Industry Research Center analyzed all 554 major Division I infractions decisions from 1953 to 2014. While penalties varied due to several factors -- including whether the programs were repeat offenders -- “NCAA conference membership generally has no influence on the severity of penalties,” the study concluded. An exception to this, the researchers found, were cases involving football at a Power Five institution. Those cases were associated with longer postseason bans.

About 40 percent of major infractions cases occurred in those Power Five leagues, which include the Atlantic Coast Conference, the Big Ten, the Big 12, the Pac-12 and the Southeastern Conference. Out of the 554 cases, nearly 83 percent involved men’s basketball or football. The most common types of cases were those involving extra and impermissible benefits. About 12 percent of cases were academic fraud cases.

Nearly 85 percent of cases involved coaches, the study found, and 43 percent involved athletic boosters. Prior to 1984, 9 percent of violations were self-reported. Since then, 48 percent of violations have been self-reported. Probation was a penalty in 86 percent of all major infractions cases, with two years being the most common length of probation. Postseason bans (42.2 percent) and scholarship reductions (45.5 percent) were also common.

In the last year, the NCAA’s infractions process has come under scrutiny, in particular by programs facing high-profile investigations by the association. In November, the NCAA announced that the University of Notre Dame must vacate two years of football wins, including those from a season in which the team competed for a national title, after a student athletic trainer completed class assignments for several football players in nearly two dozen courses. Notre Dame decided to appeal the penalty, however, arguing that the punishment is “unjustified,” as no university officials were involved in the academic misconduct.

The university also argued that the punishment was “discretionary and should not be applied in this case.” While it’s true that vacating wins is not a mandatory punishment, the NCAA argued, “prescribing vacation as a penalty in cases involving academic misconduct is historically consistent with the membership's bylaws.”

In September, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill told the NCAA that it does not have the authority to punish the university for what is widely seen as the most egregious case of academic fraud in the history of intercollegiate athletics. For 18 years, some employees at UNC Chapel Hill knowingly steered about 3,000 students toward no-show “paper courses” that never met, were not taught by any faculty members and in which the only work required was a single research paper that received a high grade no matter the content. UNC's argument: the NCAA has no jurisdiction over assessing the quality of an institution's courses, even when those courses were fake and involved more than 1,500 athletes.

Earlier this month, John Swofford, the commissioner of the ACC, of which UNC is a member, said he had concerns about how the Committee on Infractions functions. The committee is comprised of college administrators and athletics employees, including presidents, athletic directors and conference commissioners. Greg Sankey, the commissioner of the Southeastern Conference, is the committee’s current chair.

“I have great respect” for Sankey, Swofford said. “I think the structure itself, the whole structure -- and we've had it for years, it's nothing new -- of judging each other, that's a tough place to be.”

Swofford also said he was worried about how long the UNC investigation was taking, saying it had started “at the turn of the century.” (The UNC scandal, in fact, came to light in 2011.) The ACC commissioner is not the only person who has expressed concern about the length of some infractions cases. Earlier this week, a member of the Mississippi state Legislature proposed a bill that would require the NCAA to complete investigations within nine months. The proposed legislation is in response to a still-unresolved investigation that began at the University of Mississippi in 2012.

“There’s a lot of myth out there; there’s a lot of misconceptions about the process,” Carol Cartwright, former president of Kent State University and the committee’s chief hearing officer, said Thursday. “Do some institutions get treated more harshly? Are there some conferences that get off easy? All that floats out there in the membership and in the general public. So we saw this [new study] as a major opportunity to reinforce our commitment to clear communication and transparency.”