You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

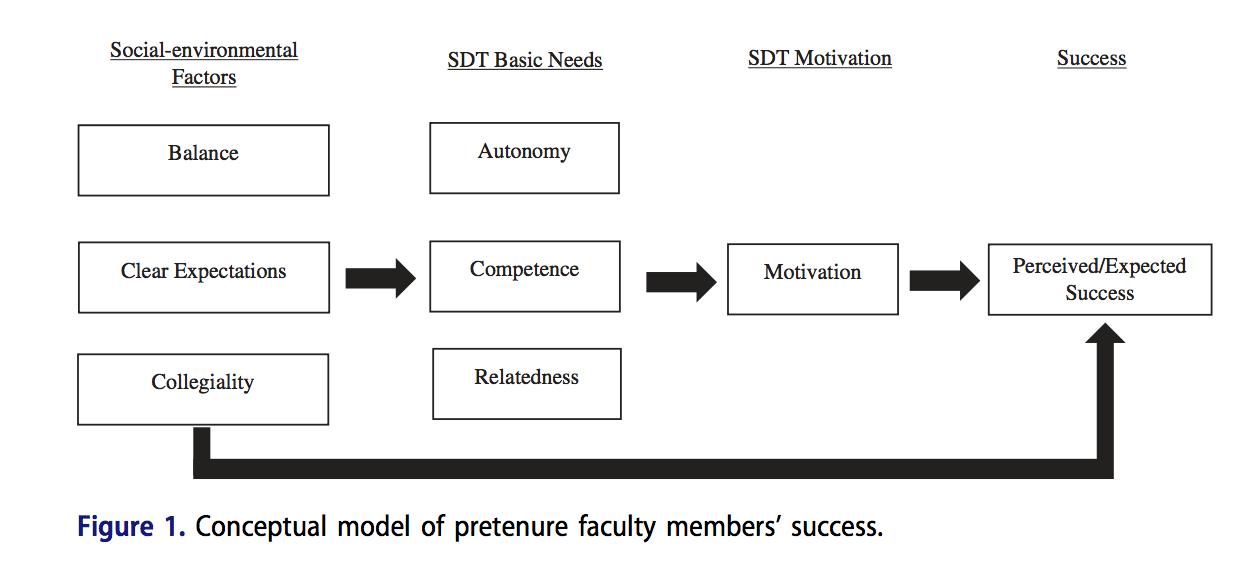

Both hiring and signing on as a new assistant professor involve risk; if the commitment doesn’t work out, both the institution and the faculty member denied tenure have lost valuable time and resources. Naturally, then, there’s a large of body of literature on how to promote junior faculty members’ success, and a new study builds on three recurring themes: balance between research, teaching and service and between work and home; clear expectations about professional responsibilities; and collegiality.

The study’s authors proposed and tested a conceptual model of pretenure faculty success that incorporates additional research on motivation -- namely self-determination theory. The gist is that when pretenure faculty members’ social-environmental concerns are addressed, “their basic psychosocial needs will be satisfied, resulting in optimal motivation and greater reported success in teaching and research.”

Self-determination theory asserts that human motivation is a continuum, with inherent or intrinsic motivation being the ideal. And intrinsic motivation is hypothesized to occur when a setting fulfills one’s senses of autonomy, competence and “relatedness,” or feeling connected. So the new study’s authors guessed that balance, clear expectations and collegiality generally predict pretenure faculty success because they support feelings of autonomy, competence and relatedness -- which, of course, promote intrinsic motivation and success.

Source: The Journal of Higher Education

The authors evaluated their model by analyzing 105 pretenure faculty members’ survey responses from two unnamed public research universities in the Midwest. Because success is difficult to define, they in their survey asked faculty participants about their perceptions of their teaching and research success, respectively, in relation to their personal standards, departmental standards and, finally, other faculty members. They also asked faculty members how successful they expected to be based on their own standard.

Participants rated their level of agreement with statements on balance, clear expectations and collegiality, such as, “I have been able to balance my work and home/personal life,” and “There is a colleague in my department whom I can ask for advice and guidance.”

To assess faculty members’ perceived levels of satisfaction in terms of autonomy, competence and relatedness -- which set the stage for intrinsic motivation -- additional survey items included, “In my [teaching/research], I feel a sense of choice and freedom” and “I feel confident that I can do things well on my [teaching/research].”

Additional items assessed faculty members’ source of motivation for various tasks. Possible answers corresponded with internal or external factors. “Because it is pleasant to carry out this task” was intrinsic, while “Because I am paid to do it” was not, for example.

Through path (or extended multiple regression) analysis, the authors observed relationships between social-environmental factors and basic psychological needs, as suspected. Unsurprisingly, the strongest pathway was the connection between collegiality and relatedness, especially in terms of teaching. Collegiality was positively correlated with perceptions of autonomy and competence in teaching.

Teaching "can be highly collaborative as faculty members within departments work together on curriculum development, which often involves exchanging materials, and assessment,” the study says. “Furthermore, because pretenure faculty typically have limited training in teaching upon starting their position, they regularly require support from colleagues to be successful.”

In contrast, perceived balance was most strongly related to autonomy and competence in terms of research. Why? “Establishing a good routine and finding time for research appears to be most important for research motivation,” the paper says.

As much as shifting performance targets can rile faculty members, clear expectations were not significantly related to the basic psychological needs or intrinsic motivation of pretenure professors with regard to teaching or research. They were, however, correlated with extrinsic motivation in both domains. That’s possibly “due to faculty expectations (e.g., for tenure consideration) typically being ‘externally’ set by university administrators, thus aligning more closely with introjected and external motivation."

An unexpectedly significant path, meanwhile, was the negative relationship between clear expectations and perceived success in research. The finding suggests that for some faculty members, “a clearer understanding of the criteria for research success may be demotivating, as perhaps identifying challenging goals for tenure contributes to feeling a lack of accomplishment in the present,” the study says.

In support of self-determination theory’s application to pretenure success, the paper says that survey participants who perceived their basic psychological needs as being satisfied also tended to report higher levels of intrinsic motivation. Specifically, relatedness mattered in terms of teaching, and perceptions of autonomy and competence mattered to research.

One note: faculty members at the institutions studied had average workloads of 50 percent teaching and 35 percent research. These relationships are “likely to differ for faculty at institutions in which greater relative emphasis is placed on research activities,” the study warns.

Intrinsic motivation was also linked to higher expectations of future success. That is, pretenure faculty members who reported engaging in teaching and research because they found it enjoyable or interesting tended to say they felt more successful and also expected to be successful in the future, according to the study.

Also noteworthy is that extrinsic motivation was not significantly related to pretenure faculty success. That’s not surprising, the authors say, given that few enter academe to become rich or due to other outside pressures.

The authors call for further study but say that support for their model “will allow researchers, faculty development officers, university administrators and faculty members themselves to more fully understand the ideal pathway to success and perhaps lead to better understanding of how to assist those who are falling short.”

Even more practically, they say, their results suggest that university administrators -- including department chairs -- “could promote teaching effectiveness in pretenure faculty by fostering supportive relationships among departmental colleagues that, in turn, contribute to perceptions of relatedness, teaching-related enjoyment and reports of greater success.”

For example, pretenure faculty members could be assigned a teaching mentor willing to share existing course materials, review course syllabi, discuss textbook options or observe them in class, the study says.

“Alternatively, our findings suggest that efforts to promote pretenure faculty research should ideally encourage autonomy as well as a balance (teaching/research and work/life) through provisions such as teaching releases for research purposes, gym memberships for health promotion or designated periods when faculty need not respond to email (e.g., weekends). Such initiatives would be expected to contribute to sustained faculty interest in research and, in turn, greater research-related success.”

“Testing a Model of Pretenure Faculty Members’ Teaching and Research Success: Motivation as a Mediator of Balance, Expectations and Collegiality” was published this week by The Journal of Higher Education. Asked about the stickiness of collegiality in academe -- the American Association of University Professors opposes its use as a criterion in personnel decisions, for example -- co-author Robert H. Stupnisky, associate professor of education and human development at the University of North Dakota, said he could only point back to his finding that collegiality is an important predictor of faculty motivation and perceived success in the teaching domain.

Stupnisky's co-authors are Nathan C. Hall, associate professor of educational and counseling psychology at Canada's McGill University; Lia M. Daniels, associate professor of educational psychological at the University of Alberta in Canada; and Emmanuel Mensah, of the North Dakota Department of Public Instruction.

Cathy Trower, an independent consultant on higher education who has studied faculty success extensively, said the new model seems to have broad applicability, and theoretical grounding enough to “pass the sniff test.”

“This research is some of the best I have seen on this subject,” she said. “It appears well conceived, well executed and thoughtful.”