You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Library directors are growing increasingly confident about the directions in which they are moving their organizations, a new study found, but the rest of the campus may not have gotten the memo.

The Ithaka S+R Library Survey 2016, released this morning, builds on findings from the 2013 edition. It shows many library directors are becoming comfortable with the idea that the library may no longer be the starting point for research, and that they are forging ahead with plans to further boost libraries’ ability to support students and faculty members with their teaching, learning and research.

Those plans are facing some resistance. Many faculty members value that the library acquires and stores the books and journals they need for their scholarship and want them to keep doing so while also expanding their services. Compared to the last survey, conducted in 2013, fewer library directors now say they agree with their direct supervisor about the direction in which to take the library. And insufficient funding continues to place constraints on library directors’ ability to make change.

Yet “the redirection of the academic library continues,” writes Roger C. Schonfeld, director of Ithaka S+R’s library and scholarly communication program. “Academic libraries are in transition away from serving principally as collection builders and content providers, where size is a metric of success. Many leaders see a future where they will be valued for the contributions they make in support of instruction and learning, and in the case of research universities, in support of research, including their distinctive collections.”

The survey, which is based on responses from 722 library deans and directors at nonprofit four-year colleges and universities in the U.S., provides an overview of the academic library landscape at a time when many libraries are renovating, reorganizing and, broadly speaking, rethinking their priorities.

The findings show that work is being led by many library directors who are relatively new on the job. More than half of the respondents (55.2 percent) said they have held the position of dean or director for less than five years. About one-quarter (26 percent) said they have more than 11 years of experience.

That doesn’t mean the reorganization projects are being led exclusively by newcomers to the academic library, however. Some of it reflects the general trend of more frequent job-hopping seen in today’s employment market.

Arizona State University is one example. The university recently got the green light to proceed with a plan to renovate of its main library on campus and hire about 25 new staffers. The project is expected to cost more than $100 million. ASU in 2014 hired James J. O’Donnell, a former Georgetown University provost, to lead the library through the process.

In an interview last month, O’Donnell said the scope of ASU’s plans was one of his main reasons for taking the job.

“The situation in the library and the institution here was one where they didn’t need a custodian,” O’Donnell, who served on Ithaka’s advisory board for this survey, said. He said ASU was looking for “significant change and significant progress,” and not for “someone to come in and not mess up.”

Library directors at large research universities such as ASU are focusing intently on improving services that support teaching, learning and research, which is reflected in their constraints and hiring plans.

Compared to those at baccalaureate and master’s institutions, library directors at doctoral institutions were more likely to name a lack of employee skills in key areas as one of their primary constraints. And looking ahead to the next five years, those library directors said they expect to hire new staffers who will focus on a range of specialized topics, among them data analytics, digital humanities and preservation (click the thumbnails to see full-size images).

“What you can see there are the absolutely dramatic differences that are being imagined at doctoral universities versus smaller, teaching-oriented institutions,” Schonfeld said in an interview. “Doctoral directors are especially confident about where they’re going, and they need people to help them get there.”

Library directors at large research universities are slightly less constrained by their budgets than those at smaller institutions, but they also face a little more resistance from their own staff members, the survey results show.

“It’s a bigger ship to turn, there’s a clear sense of the new roles that are emerging and there’s more organization distance from the director to the front line,” Schonfeld said. “All three of those things are co-occurring in the doctoral institutions.”

Disagreement on Student Skills

Library directors continue to say that supporting student success is their No. 1 priority. They do so in a number of ways: providing reference instruction, supporting online instruction and simply being a physical space on campus where students can collaborate and study.

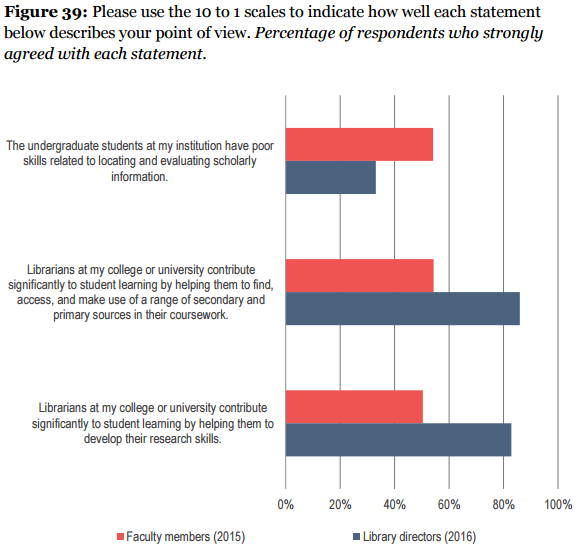

Compared to faculty members, however, library directors have a vastly different view of the impact of those efforts.

More than 80 percent of the library directors surveyed said they “contribute significantly” to student learning by helping them discover scholarly sources and develop their research skills. Faculty members are evenly divided on the question, according to the faculty survey Ithaka published last year.

Faculty members are also concerned about their students’ ability to find and evaluate scholarly information -- slightly more than half of the 9,203 faculty members surveyed rated students’ skills as “poor.” About one-third of library directors said the same.

The library directors’ responses are perhaps particularly interesting, Schonfeld said, as the survey was fielded last fall during the height of an election season in which “fake news” featured prominently.

“It has me wondering if they’re … thinking about the same sets of issues,” Schonfeld said. “What is it that seems to cause faculty responses to be more critical of students that library director responses?”

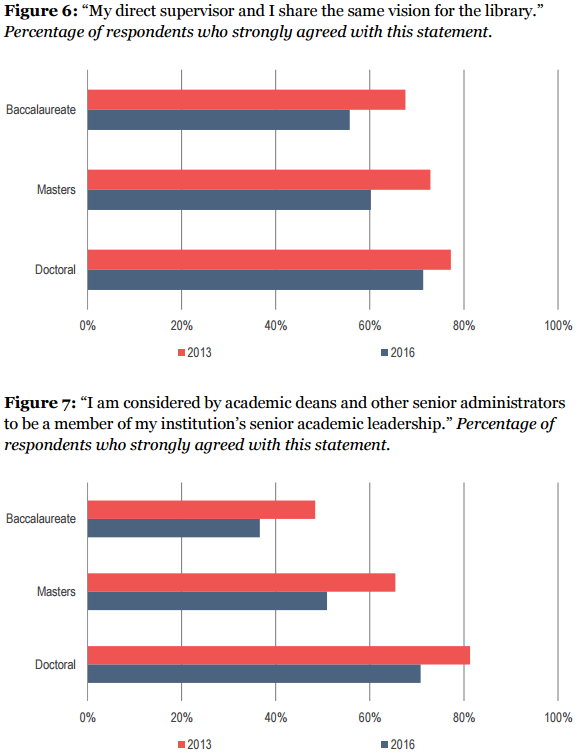

At the same time, the distance between library directors and their immediate supervisors is growing. The share of library directors who said they share the same vision for the library with their supervisor is down about 10 percentage points from the 2013 survey (though a majority are still in agreement), and fewer library directors now say they are considered a member of their institution's senior academic leadership.

“You get the sense that, as a group, they’re pursuing these new directions,” Schonfeld said, “and yet you have these indications that suggest … they haven’t fully realized the fruits of their investments.”

“They’re laboring to make a transition and offer new services and generate new sources of value.”