You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

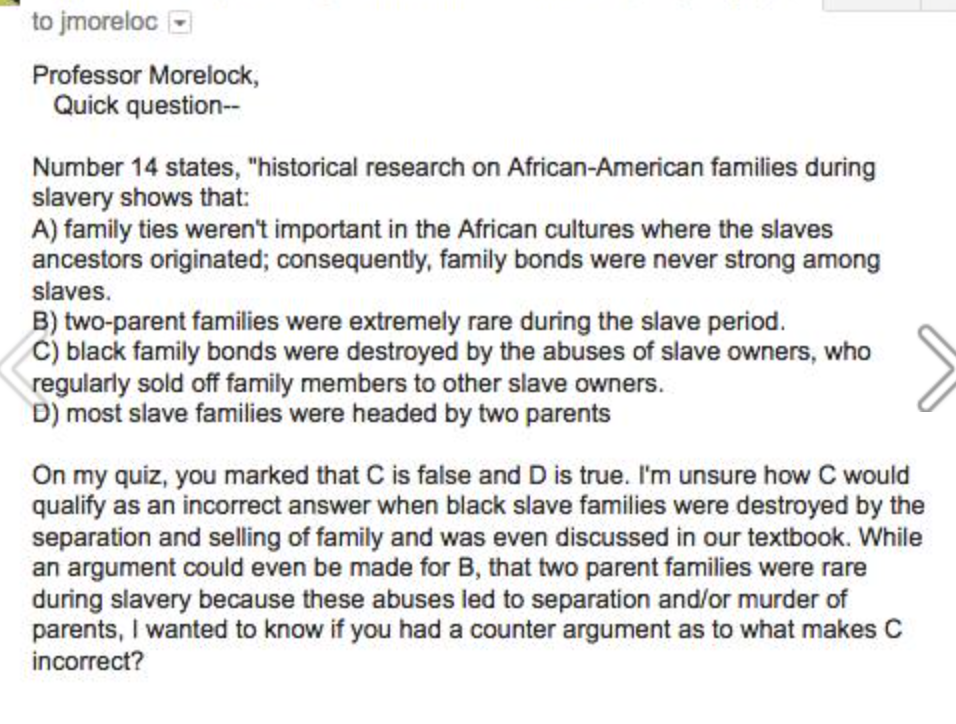

It started with a question on a quiz: “Historical research on African-American families during slavery shows that …” A student took exception to what her instructor said was the correct answer, an email exchange ensued and things escalated.

The University of Tennessee at Knoxville allegedly terminated the instructor, and the student is now celebrating on social media, saying she “got a racist professor fired midsemester after she tried to sabotage me.” What exactly happened?

In February, Kayla Renee Parker, now a senior, answered the question about enslaved families on a sociology quiz administered by longtime lecturer Judy Morelock. Parker, who has since shared the story online, was sure the answer was “C) Black family bonds were destroyed by the abuses of slave owners, who regularly sold off family members to other slave owners.” Plenty of historians would agree.

Yet Morelock marked it as wrong, saying the correct response was “D) Most slave families were headed by two parents.” To Parker, something was off, since her textbook mentioned the separation of families by the slave trade. She emailed Morelock to ask why “C” couldn’t at least also be true, according to messages she shared on Facebook.

Morelock responded that most families remained intact, noting she’d emphasized that in class, but she asked Parker for evidence in the textbook of her answer. Parker responded with a specific page and quote, and Morelock quibbled with it before saying she’d give Parker and everyone else in the class an extra four points.

Problem not solved, though, according to what Parker recently wrote in a blog post on Medium called “Beware of Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing: The Tale of a Progressive Professor Who Forgot to Hide Her Racism and Got Her Ass Fired.” Among other criticisms, Parker says Morelock relied on outdated research that “whitewashes” the realities of slavery to back up her argument and, worse, presented “alternative facts” to the class. That’s based in part on an email the instructor sent to her saying some scholars have argued that slaves’ family bonds “were maintained in part by word-of-mouth communication from a slave community on one plantation to a slave community on [another]. Further, as I said in class, many slave owners tried not to make their charges angry by selling off the most important people in the lives of their slaves.”

It was “alarming to me that my professor believes that ‘Most slave families were kept intact with wife and husband present,’” Parker wrote in her post. “What does she think this was, Good Times? Most slaves were not getting married and most slaves were not raising their children.”

Parker also accuses Morelock of retaliating against her in class for discussing the dispute in Facebook posts, which the instructor had allegedly been reading. “Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to bring the textbook to class today because my bag is full of other texts for a student who requires further evidence on subjects I teach in class,” Morelock allegedly said, for example.

A subsequent one-on-one conversation resulted in a kind of challenge for Parker to lecture the class on the topic, she says. Parker talked with the department chair about possibly being retaliated against for accepting the offer but ultimately did so, streaming the talk on Facebook.

“I felt as though I had to give this presentation because I have had enough of white people defining my history, especially inaccurately. Our country continues to have a race problem and I firmly believe that it’s because we can’t even accept that America has never been great for anyone unless you’re white,” Parker wrote. “How can we expect the treatment of black people to improve and equality to be made possible if America can’t even face the reality of how people of color have been treated in the past? It’s impossible to move forward if we can’t look back.”

Soon, she says, friends alerted her to alleged threats Morelock had been posting on her own Facebook page. Parker attributes the following comments to Morelock, which she assumed were in reference to her: “After the semester is over and she is no longer my student, I will post her name, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn … after she graduates, all bets are off,” “I don’t forget malevolent attempts to harm me. #karmawillfindyou,” and “Ignore the facts, promote a misinformed viewpoint, trash me and I will fight you.” Screen shots have been circulated, but Morelock says some of the comments were not about Parker.

Parker says she was removed from the class and otherwise supported by administrators, while Morelock allegedly offered a two-part coup de grâce: a final email to the family sociology class saying she'd likely be terminated without an opportunity to defend herself because a student had impugned her character in a formal complaint, and a vulgar Facebook meme involving a gift-wrapped dildo Parker says was directed at her (Morelock denies this).

Over all, Parker accuses Morelock of being a false ally to people of color. “She wears a safety pin so everyone knows she’s an ally for minorities,” reads the blog post. “She regularly discusses her love for the Obamas, the Black Lives Matter movement and her admonishment for this current administration. However, I would soon realize that nothing would shake her more than a confident black woman contradicting her in front of a classroom of her own students.”

Tennessee’s sociology chair declined to comment on the matter, saying that would violate federal student privacy laws. Karen Ann Simsen, a university spokeswoman, said she couldn’t address Parker’s comments for the same reason. But she said Morelock was notified last summer that her year-to-year contract would not be renewed for this coming fall, as the sociology department is “phasing out a few of the courses she teaches from the curriculum” and using more doctoral students to teach undergraduates.

In April, Simsen said, “we exercised the option outlined in our Faculty Handbook of ending her contract early” by paying her remaining salary though July.

Morelock said via LinkedIn that the university had “threatened” her and she couldn't talk to reporters, lest her payout be revoked. But she said the blog "is replete with scurrilous falsehoods from the very first sentence. Some of the comments lifted from my page were not intended for that person and I did not send the dildo meme to her. It was lifted from my pictures."

Morelock shared a letter from a past student expressing shock at the situation, since she'd always known her instructor to be a "champion of social justice." The former student said Morelock was bothered by having her integrity and commitment to her students of color questioned on social media, not by being challenged over a test question, and Morelock agreed. She referred additional requests for comment to Donna Sherwood, a retired professor of English at Knoxville College, where Morelock used to teach, and lecturer of women’s studies at Tennessee. Sherwood said via email that she was “still stunned at the traction” one young woman “with a vendetta has been able to achieve. I'll give her credit for persistence and appeal to racial hysteria.”

Sherwood said her knowledge of the case was based on the public record due to Morelock's “gag order,” but described the situation as a student interested in proving a teacher wrong engaging in "Facebook attacks until the teacher responded -- and went a bit overboard.” Even so, she wondered why Parker continued to draw attention to the case even after Morelock was terminated, saying theirs was an “academic disagreement, which should have stayed in academia and not spilled over into social media, where hysteria quickly supersedes intellectual pursuit of knowledge.” (Parker has elsewhere said she waited to blog about the class until grades were posted.)

Parker said Tuesday that Morelock “loses credibility when saying she wasn't harassing me, when there is photo evidence of the public Facebook posts she was making.” Morelock seems to believe that calling her a racist is “libelous,” Parker said, but her actions “continue to prove my point.”

To some, the case will come across as a one-off, a unique situation in which a soon-to-retire instructor overreacted to a student. Others will -- and do -- see it as a case of racial bias by a white professor against a black student with a legitimate academic concern. Others still will see a non-tenure-track professor being given no apparent opportunity to defend herself against claims with implications for academic freedom. Many may see it as a reason to exercise privacy settings on Facebook, or stay off it altogether.

But what about that quiz question? Was Parker right? Brenda Stevenson, Nickoll Family Endowed Chair in History at the University of California, Los Angeles, and an expert on enslaved women and families, said neither answer is completely true, but that “C” -- Parker’s answer -- would be “most true.”

Jerome Dotson, an assistant professor of Africana studies at the University of Arizona who studies slavery, said he’d been following the case and found the question to be poorly worded over all, in that no response fairly represents the antebellum slave family. (He said the question could work better as an essay.)

Attributing broken family bonds to the slave trade eliminates “any possibility for slave agency, and it gives too much attention to the slave owner’s power,” he said, since threats of sale were obvious problems for slaves but there were still families. In fact, he said, “the slave family helped form the cornerstone of the slave community,” and some slave owners permitted enslaved men and women to marry to keep them from running away.

Morelock’s preferred response, meanwhile, is problematic because of the wording, Dotson said. He'd be reluctant to argue that “most” slave families were headed by two parents, since, for example, Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs were reared by their grandmothers, he said.