You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

With the dearth of available tenure-track faculty positions, professional organizations and others are working to change how Ph.D. programs prepare students for the careers they’re likely to have outside academe. In good news for those efforts, a new study of some 5,000 humanities and social sciences Ph.D.s finds that those working in nonprofits are more satisfied with their jobs than are their peers in tenure-track faculty positions. That’s true even for Ph.D.s who intended to work in academe but did not end up there.

The working paper, from the Cornell Higher Education Research Institute at Cornell University, also found a surprising level of permeability between academic and nonacademic work -- meaning that one’s early career isn’t necessarily a referendum on their subsequent success in academe (or lack thereof). Moreover, it found that having children isn’t the death knell for tenure-track faculty success for women that some say it is, at least in the long term.

“These findings have the potential to help doctoral students envision and prepare for their careers, as well as to counteract perceptions held by some students that taking a non-tenure-track job or having young dependents in the household early in the career may preclude academic careers,” the study says. “Rather, our findings suggest that doctoral students, administrators, faculty and other stakeholders employ more flexibility in imagining the work lives of Ph.D.s and the many ways and roles in which Ph.D.s can use their training.”

The study, led by Joyce B. Main, assistant professor of engineering education at Purdue University, is based on data from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation’s Graduate Education Survey. That survey offers comprehensive longitudinal data sets tracking humanities and humanistic social sciences students from the beginning of their Ph.D. training at more than a dozen selective research institutions through at least eight years after degree completion. The researchers were interested, in particular, in the likelihood of the Ph.D.s becoming tenure-track professors at three different postgraduation points: six months, three years or eight years or more (the last check-in point was 2011). They also wanted to know about the degree of movement between positions in business, nonprofits (including government) and academe -- both on and off the tenure track -- along with job satisfaction across sectors.

More than that, the researchers used the “life course” multidisciplinary theory of human agency to examine the influence of gender, marital and family status and other demographic factors on the pathways studied. Significant attention was paid to the long-term career outcomes for Ph.D.s who were parents within six months of completing their degrees and those who were not.

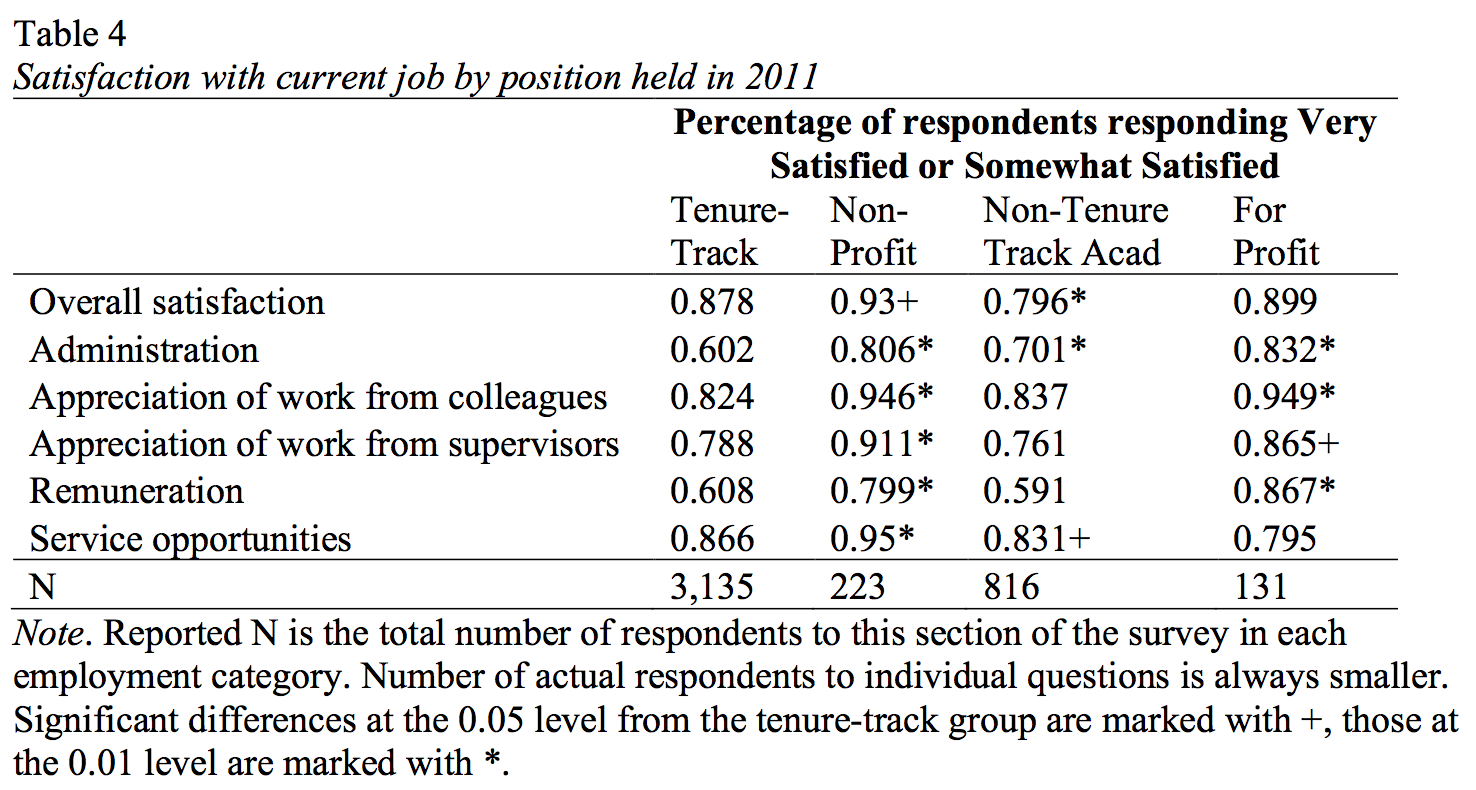

Job Satisfaction

Over all, a greater proportion of Ph.D.s employed in the nonprofit sector reported being satisfied than those in tenure-track positions. Some 93 percent of Ph.D.s in nonprofits said they were “very satisfied” or “somewhat satisfied” with their current position, compared to 88 percent of Ph.D.s in tenure-track or tenured jobs. Compensation seemed to a play a big role, with some 80 percent of nonprofit workers saying they were satisfied with their remuneration, compared to 61 percent of their tenure-line faculty peers. Ph.D.s working in business or for-profits weren't as happy as those in nonprofits but they still reported being happier than their tenure-track peers across most metrics. Those working in academe off the tenure track were the least happy overall.

No surprise, the authors found that having aspirations to become a tenure-track faculty member was a strong predictor of becoming one across the three time frames studied. There were also Ph.D.s who held non-tenure-track and nonprofit jobs six months after graduation who held tenure-track positions by 2011, the latest period studied, “suggesting that there were a number of Ph.D.s who took specific actions and made choices that helped them obtain their intended career goal,” the paper says.

The authors note that just 5 percent of Ph.D.s studied worked in nonprofits, compared to 70 percent working in academe -- a small sample size. Still, they say, job satisfaction by sector was strikingly consistent across demographic groups and the over sample of 5,000 Ph.D.s.

The American Historical Association is among those groups working to diversify Ph.D.s' job aspirations and training. Emily Swafford, the association’s academic affairs manager, said she wasn’t surprised by the satisfaction findings, since AHA has learned over time that many graduate students “aren't able to envision the work of being a professor, making the transition from graduate student to professor difficult and perhaps disappointing.”

James Grossman, executive director of the AHA, said association data suggest that the 20 to 25 percent of history Ph.D.s working outside academe tend to report being “quite happy” with their career outcomes -- so much so that many have offered to volunteer with AHA’s career diversity initiative, especially as email correspondents with graduate students interested in paths beyond the professoriate.

Linked Lives

Also unsurprisingly, and consistent with the life course perspective that social contexts matter and that lives are “linked,” the authors found that marital and family status influence employment patterns. Among married Ph.D.s, those whose spouses were students at the same time were more likely to obtain tenure-track faculty positions compared to married Ph.D.s whose spouses were unemployed or employed outside academe. The paper says this may be due “to shared values and understanding of the academic path, and perhaps related to academic institutions’ increasing attention toward supporting dual careers.”

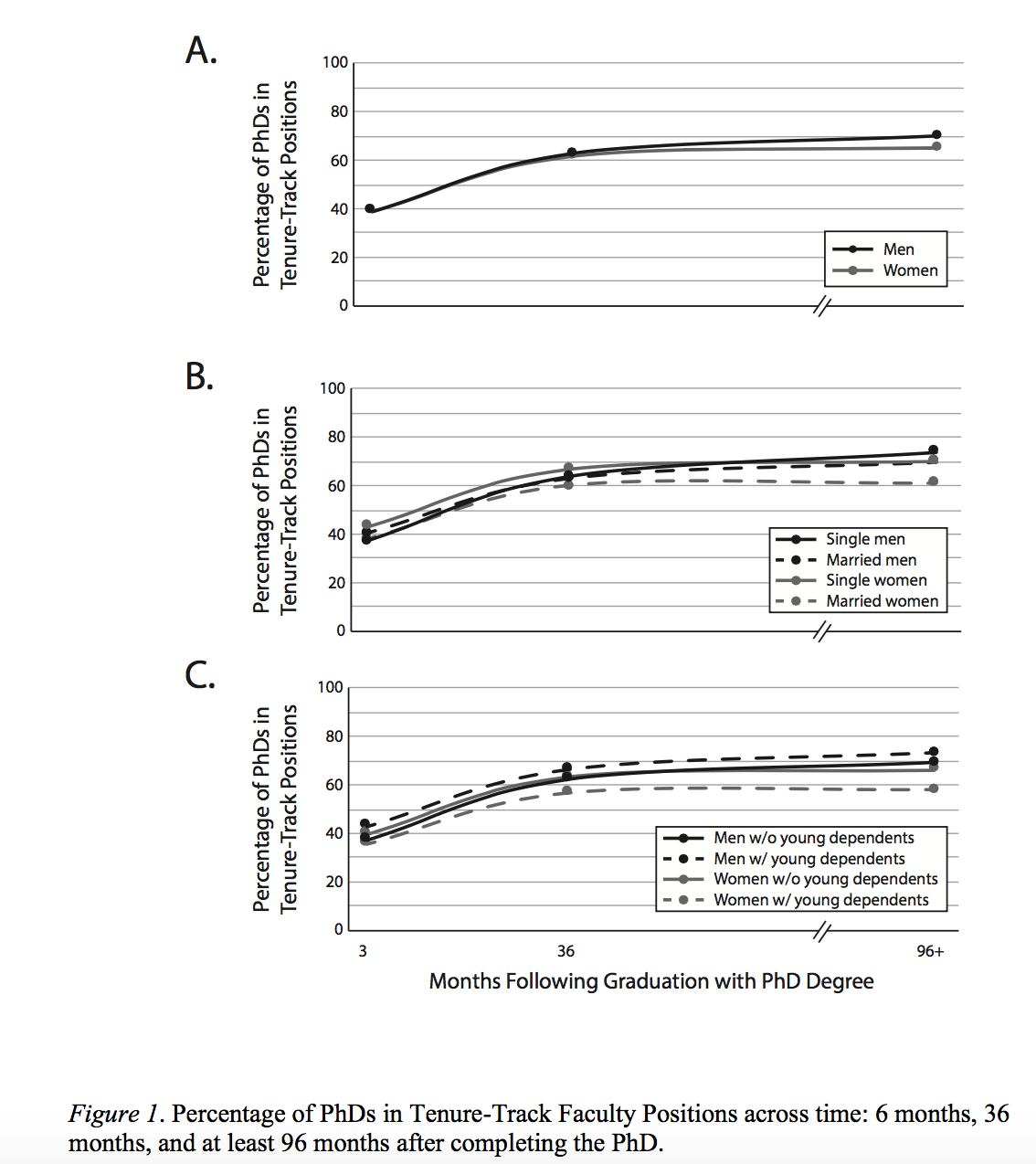

Yet again, unsurprisingly -- given the wealth of research showing that women bear a disproportionate responsibility in child rearing -- marriage and having a child within six months of degree completion appear to affect male and female Ph.D.s differently. Women were less likely to hold tenure-track faculty positions if they were married or had young dependents six months after degree completion. Consistent with other studies, the authors wrote, it’s hard to say whether that particular finding is due to individual choice, structural factors across institutions or hiring practices that constrain women’s choices -- or a combination of those.

By 2011, however, at least eight years after degree completion, the effect of children at home so diminishes that women who were mothers within six months of getting a Ph.D. were about as likely as women without children six months after getting a Ph.D. to hold a tenure-line position, controlling for a number of factors.

The data don’t provide much insight into that trend. The authors guess it could be attributable to higher levels of gender equity in some fields than others, as well as changes in individual time allocation, household routines or in children’s needs as they get older.

The authors say that examining the longer-term career outcomes and the life course -- rather than just the first position after a Ph.D. -- provides a different perspective on women’s work lives.

Traveling Between Academe and Nonprofits

Stephen Ceci, the Helen L. Carr Professor of Developmental Psychology at Cornell, has previously found evidence that women’s life choices play a bigger role in their academic careers than gender bias or other factors (with some field-specific qualifications). Ceci wasn’t involved in the new study but said its “real headline” seems to be the relatively large numbers of Ph.D.s who started out in nonacademic jobs and then segued into tenure-track positions within eight years of getting a doctorate.

“This runs counter to the prevalent wisdom that we used to share with our graduate students” who wanted faculty jobs, he said -- namely, that it’s important to get on the tenure track right away. In the 1970s and ’80s, Ceci added, “when many of us were trained, it was probably the case that when a Ph.D. decided against going on a tenure-track job immediately after finishing their training, it may have signaled a lack of commitment to the profession or sheer fickleness or weak credentials.”

The new study says that Ph.D.s who held non-tenure track positions six months after getting a Ph.D. were 30 percentage points more likely to enter a tenure-track or tenured position within three years of the Ph.D., compared to Ph.D.s working in business. Those who were initially employed in nonprofits were 10 percentage points more likely than Ph.Ds working in the for-profit sector to have obtained a tenure-track faculty position three years after earning a doctorate.