You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The American Journal of Political Science is one of the field’s most esteemed publications. So visitors to the journal’s main webpage were everything from incredulous to irate about what they saw there earlier this week: instead of just political science news, editor William G. Jacoby had posted a message denying the sexual harassment allegations he’s facing.

“It is apparently widely known that allegations related to sexual harassment have been made against me,” began the editorial note from Jacoby, a professor of political science at Michigan State University. “The allegations are untrue. I never engaged in the behaviors described in the allegations.”

Jacoby also used the highly visible space to announce that he’d be stepping down as editor of the journal at the end of December, of his own accord but due to “circumstances.”

In so doing, he continued to refute the allegations. While he is cooperating with several ongoing investigations into his conduct, he said, the charges are not going away, “despite their false nature.” Therefore, Jacoby wrote, “I do not want any questions about me as an individual (rather than as a scholar or editor) -- unfounded as these questions are -- to have any detrimental impact on the incredible, great things that have been accomplished at the journal so far.”

Jacoby’s public troubles began in January, when Rebecca Gill -- a former student of his who is now an associate professor of political science at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas -- shared a personal account of harassment during a mentoring panel at the Southern Political Science Association and on social media. A professor once asked Gill to have an affair, she said, making her doubt if he’d ever actually been interested in her graduate work at all.

Gill did not mention Jacoby by name and told Inside Higher Ed at the time that her main motivation in speaking out was to help faculty mentors and students understand how harassment can contribute to impostor syndrome. That’s the feeling -- common among graduate students -- that one doesn’t belong or hasn’t earned the right to be in a certain setting.

Followers of Gill’s story soon named Jacoby in discussions online and off, however. After hearing from at least one other complainant who was encouraged to come forward by Gill’s account, the Midwestern Political Science Association -- of which the journal is an official publication -- eventually hired an investigator.

The association said in a recent, now-deleted statement on its own website that the investigation of Jacoby is complete, but its governing council was unable to reach a consensus about what to do about the findings. So instead of announcing any conclusion, it said it had accepted Jacoby’s resignation while agreeing to let him remain editor during a transition period, through the end of the year. Alternative arrangements could be made for anyone who did not wish to work with Jacoby as editor, it said.

Many association members nevertheless objected publicly and in private emails to the association, saying it was unacceptable to retain Jacoby as a gatekeeper for one of political science's top journals while it remained unclear whether he had harassed women in his field. Reasonable doubt existed as to whether or not he could be impartial to his accusers and their allies, they also said.

Powerful Platform, Personal Message

In the interim, on Tuesday evening, Jacoby published his note in the editor’s space on the journal’s landing page. In his telling, the Midwest association “conducted an investigation which I believe has been completed. Theirs is internal and I have been told that no report will be issued.”

Jacoby said he also reported the initial allegation -- presumably Gill’s -- to the appropriate authorities at Midwest, Michigan State and the University of Michigan, where the incident is alleged to have occurred during a Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research summer institute.

Michigan State’s investigation is ongoing, Jacoby said, as is Michigan’s, "although I have not yet been contacted about it.”

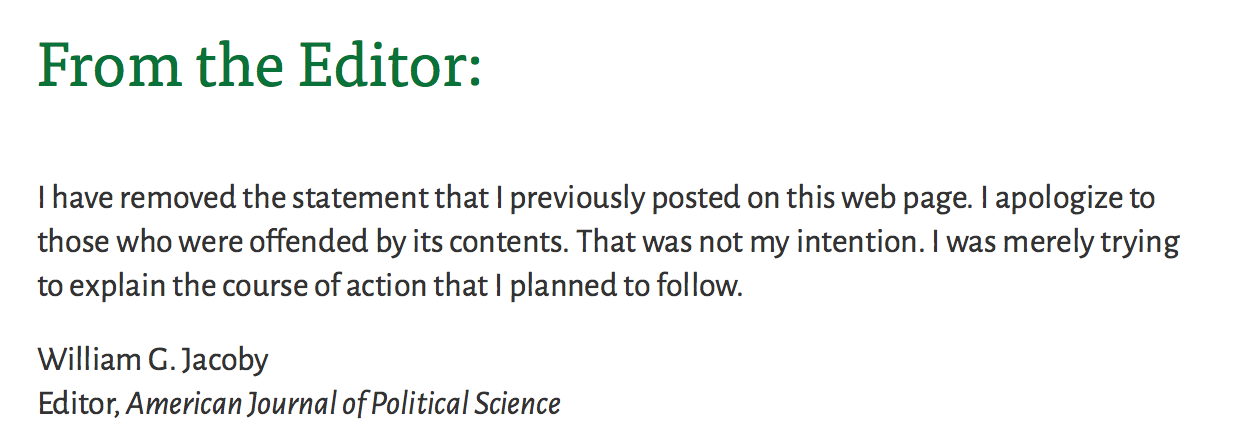

Jacoby’s statement didn’t stay up long -- he removed it Wednesday morning and replaced it with a short apology, saying he was “merely trying to explain the course of action that I planned to follow.”

But it was visible long enough to earn him and the association furious rebuke online, with many commenters saying that Jacoby used his continued position of power to assail his accusers’ credibility, effectively retaliating against and harassing them further.

Kathleen Dolan, distinguished professor and chair in the department of political science at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee, and Jennifer Lawless, a professor of government at American University, co-wrote a letter that was signed by 85 scholars last week, asking the association to terminate Jacoby’s editorship, effective immediately.

On Wednesday they announced their resignations from the organization. Lawless also resigned as a newly elected council member.

Jacoby “used the venue to defend himself, undermine the women who accused him, and send a clear signal that his editorial discretion has been severely compromised,” they said. “Although that letter has since been taken down, the fact that it was posted at all epitomizes the problem of allowing him to remain at the journal’s helm.”

Numerous other members have indicated online that they, too, plan to resign from the association.

A spokesperson for the association said Wednesday via email that Jacoby’s note “was not authorized by MPSA and doesn't represent the position of the organization or its members. We regret any offense that Jacoby's action in posting that notice may have caused.”

Any further response will be decided at an emergency council meeting at the end of the week, the spokesperson said.

Elisabeth Gerber, president of the association and Jack L. Walker Jr. Professor of Public Policy at Michigan, addressed the matter in a separate statement Wednesday, saying the emergency meeting had been scheduled due to the “firestorm” over Jacoby.

Regarding Jacoby’s post, Gerber said that the association is ultimately responsible for overseeing the journal but “not involved in any of the operations or editorial decisions.” While association officers may not act on such matters without the approval of the council, she said, they asked Jacoby to “suspend all editorial operations until the council can take formal action later this week" and he agreed.

“We regret any harm this temporary action may cause to submitting authors and intend for this suspension to last only a few days until an interim editor is in place,” Gerber added.

Jacoby told Inside Higher Ed via email that the two sets of public allegations against him "are being considered in an investigation and I cannot comment in detail, other than to say that I deny both sets of allegations and have presented to investigators evidence in support of my denial. Beyond that, I have to respect the investigative process and withhold further comment."

Filling the Void

Gill said Wednesday that she was “gobsmacked” by Jacoby’s note, but felt that “the way the MPSA handled this, it was obviously an option as to what could happen.”

Beyond Jacoby, Gill said the bigger question going forward is “how we want to organize ourselves as a discipline and what kinds of behaviors we’re going to tolerate.” For example, she said, “Do we want to treat editing a journal as a right that certain people have, or as a privilege, a service that people do for their discipline?”

Gill said she has become aware of a third Jacoby accuser, via a university investigator. That could not be immediately confirmed. But in an interview Wednesday, Valerie Sulfaro, a professor of political science at James Madison University, said she was the second accuser and that she'd shared her account of harassment with Michigan, Michigan State and, again, the association.

Sulfaro said she engaged in a consensual relationship with Jacoby when she was a 23-year-old graduate student at the University of South Carolina and he was a professor there (they allegedly continued their relationship at the same summer institute at Michigan that Gill attended).

She explained that she used the term "consensual" loosely, in that Jacoby -- the only specialist in her subfield on campus -- propositioned her in 1991 after developing a close academic connection with her, and she did not turn him down. He said he was “laying his cards on the table,” that he knew she’d been sending him “signals,” and then he kissed her in her office with the door shut, she said. The relationship allegedly continued for several years, with many awkward moments -- including Jacoby criticizing other men Sulfaro dated and her, for not acting appropriately happy in front of his wife.

Several years later, in 1996, Sulfaro encountered Jacoby at a Midwest meeting, she said. He allegedly offered her nude pictures of himself on a computer disc and became angry when she rejected them. He also kissed her without her consent at a later Midwest meeting during a discussion in a hotel room, she said.

Sulfaro said she confided in others on campus around the time of the relationship but didn’t file a formal complaint until she heard about Gill’s case.

Reading Jacoby’s post was a reminder of the dynamic of their relationship, she said, blaming the Midwest association for granting him the space to assert she's a liar.

“An absence of a summary [of findings] does not mean he’s been exonerated," Sulfaro said. "But he saw the void and stepped into it."

Lawless said Wednesday that she’s been involved with both the association since graduate school and has published in a reviewed papers for the journal. She’s therefore “deeply disappointed that we’ve reached this place,” she said. Yet she would consider rejoining the association if Jacoby were removed and the council took “steps to correct their missteps.”

“Little bandages and a less than heartfelt mea culpa, however, won’t be sufficient,” she said.

Regarding the broader academic Me Too movement, Lawless said the situation demonstrates there’s still “a lot of work to do.”

“I would have thought that the movement had taken sufficient hold outside of political science that we wouldn’t have to work so hard to convince people in positions of authority to do what seems so basic and decent” and typical in other industries, she said. “That’s not the case, but there’s no shortage of people willing and ready to work for change.”