You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Letitia Chai's senior thesis presentation

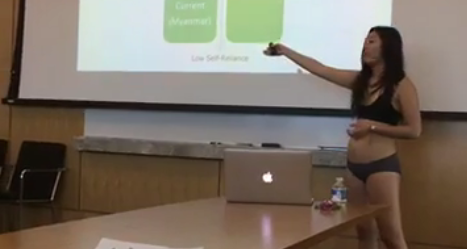

In the undergraduate thesis presentation being shared around the world, a senior at Cornell University responds to a clash with her theater professor about what she was going to wear. The professor questioned why she was wearing shorts, and the student called the comment sexist.

Ultimately, though, the story has became about what the undergraduate didn’t wear during her presentation: clothes.

"I'm more than a woman. I am more than Letitia Chai," the student said at the beginning of her talk, which she streamed on Facebook Live. Removing the same outfit her acting professor had questioned days earlier, during the practice presentation, Chai revealed her bra and underwear.

”I am a human being and I ask you to take this leap of faith, to take this next step, or rather this next strip, in our movement,” she said, “and to join me in revealing to each other and to seeing each other for who we truly are, members of the human race.”

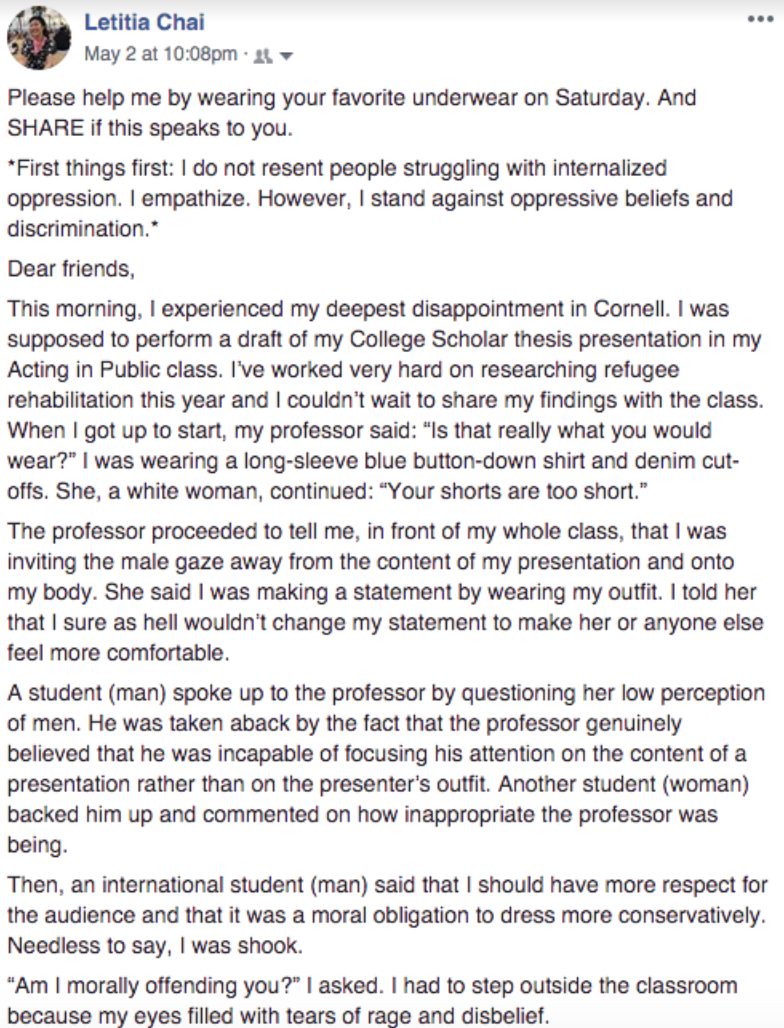

Some other students in the class reportedly removed their clothing, as well, as did followers on social media. Chai had previewed her protest in a Facebook post, saying that an unnamed professor -- later revealed to be Rebekah Maggor, assistant professor of performing arts -- had told her the shorts she was wearing were too short during the practice presentation and that she was inviting the “male gaze away from the content of my presentation and onto my body.”

Chai also said that while one male student defended her, another man in the class said that she should have more respect for the audience and that it was her “moral obligation to dress more conservatively.”

“‘Am I morally offending you?’ I asked. I had to step outside the classroom because my eyes filled with tears of rage and disbelief,” Chai wrote.

Chai said that Maggor spoke with her privately outside the theater and asked her what her "mother would say." Chai said she told Maggor that her mother is a feminist and would approve of her shorts. She said she walked back into the theater and finished her practice presentation, in her underwear.

Then, a few days later, she delivered the same presentation, streamed online, in her underwear as part of her College Scholar thesis requirement. The topic was on the host-country relationship for Tibetan refugees in India.

Different Interpretations

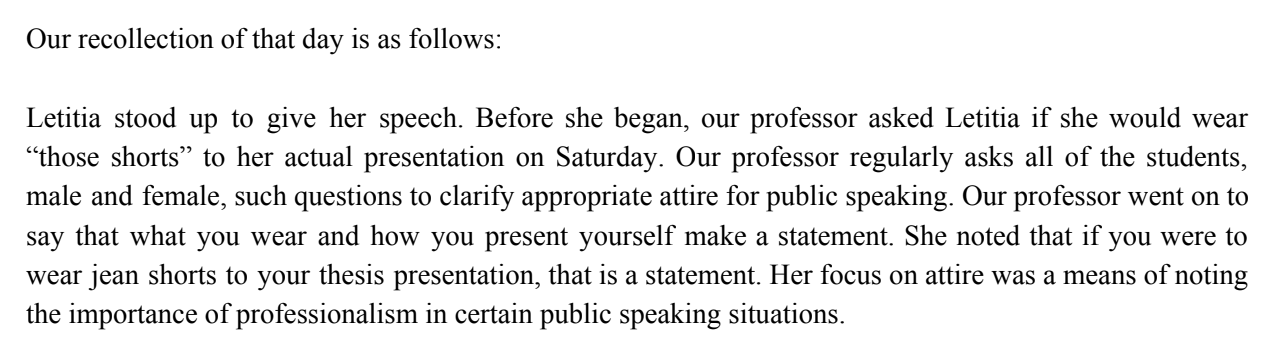

The majority of students in the seminar-size class on acting in public have since challenged aspects of Chai’s public accounts of what happened. In a public statement, the students expressed support for both Chai’s overall position and for Maggor, whom they praised as a teacher and who they said had been misrepresented in discussions about the incident.

The students said Maggor was typically sensitive to students' identities and had apologized for her choice of words regarding Chai.

Dress code controversies are more common at the high school level, most typically when students object to prohibitions against clothes deemed to be immodest or “distracting” as sexist against women. That’s because most colleges and universities do not have general dress codes, Cornell included. But some do. They tend to be religiously affiliated institutions, military institutions and historically black colleges and universities. Morehouse College, an all-male HBCU, for example, drew praise and criticism when it instituted a dress code in 2009. While some onlookers found the code befitting of Morehouse’s leadership ethos in a society where many black men face bigotry, others said banning things such as caps, do-rags and hoods in the classroom, along with women’s garb, was discriminatory in terms of race, gender and sexual orientation.

Beyond general dress codes, many pre-professional programs have codes specific to the field. Last year, for instance, Rutgers University Business School apologized after a high-profile incident at its annual career fair, in which some students were turned away due to a newly instituted event dress code. Specifics aside, the news sparked a round of criticism of dress codes as fundamentally discriminatory in nature.

Thalya Reyes, a graduate student in public policy at Rutgers, later wrote in the Daily Targum student newspaper that professionalism’s “unspoken rules stifle individuality and creativity and ultimately reinforce social hierarchies that center the white, male, cisgender, heterosexual and upper-class aesthetic. To those who do not fit this mold, existing in a professional space can be tiring or even traumatic.”

For example, she said, “the prohibitive cost of professional clothing alienates impoverished people from accessing higher-income positions so much so that there are a number of nonprofits with the specific mission of helping people in poverty access these resources.”

The Cornell case has garnered similar news coverage and attention on social media, with commenters tending to describe Chai as either a patriarchy-smashing millennial hero or someone deeply out of touch with the norms of the world she’s graduating into. “What will Chai do when she encounters a work dress code?” is a common line of inquiry among her detractors. “I have confidence in the next generation when I see stuff like this” is a common line of praise.

Chai could not immediately be reached for comment. Cornell declined comment.

Maggor said via email that she never comments “on my students' attire generally; I only comment when it's part of a performance assignment.”

She explained that after a typical warm-up on the day in question, Chai got up to rehearse her College Scholar thesis presentation.

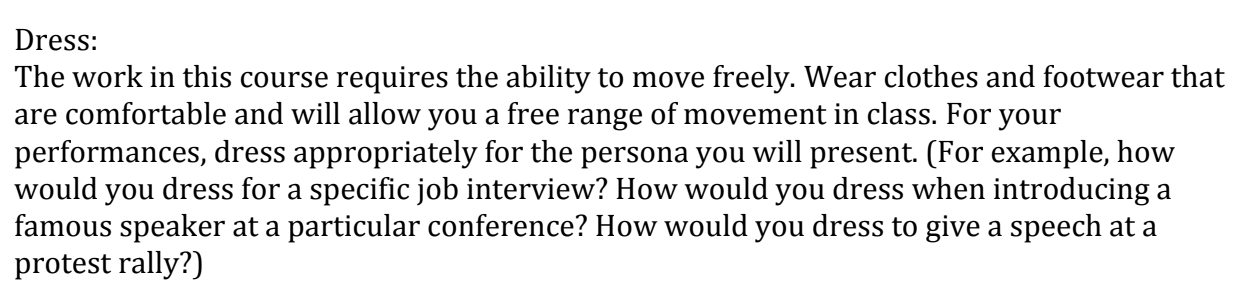

“Before she began, I asked her if she thought shorts were the appropriate choice for this particular occasion,” Maggor said. “I regularly ask my students about their attire in this class because it is a performance course; it is specified in the syllabus as something they need to consider every time they perform in class.”

Chai, however, “seemed to think that I was making a comment about shorts as inappropriate attire for women,” Maggor said. “I tried to clarify my point, but she seemed determined to interpret my question as aimed at women and her dress in particular.”

Maggor added, “As a teacher, I do not tell my students what to wear, nor do I define for them what constitutes appropriate dress. I ask them to reflect for themselves and make their own decisions. This is a public speaking class where we use various acting exercises, and ask my students to consider how they might dress for different scenarios and occasions.”

Is It Ever OK to Comment on Students' Attire?

The syllabus for the Acting in Public: Performance in Everyday Life class describes it a public-speaking course grounded in classical rhetoric and modern acting techniques. It explicitly says that dress matters. So while context is a crucial part of Chai’s case, the incident has nevertheless led to discussions about whether it’s ever acceptable to comment on a student’s attire and, if so, how.

“Did the professor make it explicit beforehand that comments on performances might include matters such as how students dress? If so, were the comments delivered in a professional manner?” Rosemary Feal, Mary L. Cornille Distinguished Visiting Professor in the Humanities at Wellesley College, said Sunday.

“Chastising" students on the way they dress is "inappropriate, and shaming young women for their clothing choices is particularly egregious," she added. "It’s bad enough when parents of daughters do it -- but a professor has absolutely no right to voice disapproval of a female student’s dress.”

Alireza Tabatabaeenejad, research assistant professor of electrical engineering at the University of Southern California, who has been following the case, said he hasn’t “dealt with an even remotely similar situation in my classes.” Yet “I would never comment on appropriateness of a student's attire, inside or outside of class,” he added, saying he couldn’t agree more with Chai’s reported comment that "I am not responsible for anyone's attention, because we are capable of thinking for ourselves and we have agency."

Tabatabaeenejad said that while he was sure Maggor “was trying to make an honest comment and didn't mean any disrespect,” she and her syllabus had nevertheless “contributed to the notion that we are responsible for others' distraction by what we wear.”

Professors should consider themselves responsible for designing a course syllabus that respects the "otherness" of students, he said, “even if the university policy or the societal stereotypes seem to ignore that otherness from time to time.”

Jennifer Saul, professor of philosophy at the University of Sheffield in Britain and moderator of the Feminist Philosophers blog, said she's commented on attire when advising Ph.D. students about job interviews. That's very different from "moralizing" about clothing choices, however, she noted.

“I've told them that it's standard to dress up for interviews and that it might harm their chances to wear jeans and a T-shirt,” she said. Still, Saul said she’s “very” careful “to make clear that I'm talking about conventions in the world that they should be aware of, rather than rules for proper behavior.”

Justin Weinberg, an associate professor of philosophy at the University of South Carolina who runs Daily Nous, another popular philosophy blog, said that if a student's attire is “explicitly relevant to the goals of the course,” as it appears to have been for Chai’s class — “then the professor is well within her rights to comment, in ways that are appropriate, given the goals of the course.”

Beyond Chai’s case, in the the absence of university-wide dress codes, a professor may comment on attire that "reasonably and significantly distracts" from the achievement of course goals, Weinberg wrote in an email. So if a student comes to class wearing a suit covered in “bright, flashing LEDs” or “nothing but a fedora,” he said, a professor may ask the student to power down or suit up, as both blinding lights and nudity are distracting.

Those are easy cases, of course, he said. The hard cases, meanwhile, “are ones in which it is difficult to tell whether the students' distraction is reasonable."

In such cases, “professors should err on the side of not commenting on their students' clothing choices," Weinberg said, partly "because commenting on the clothes may create more of a distraction than the clothes themselves." And if professors do feel compelled to comment on their students' attire, “they should do so privately, and with sensitivity and maturity.”