You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The image of the recent college graduate working as a Starbucks barista or a rental car clerk has become a cliché in the national debate over student loan debt. Studies of the underlying validity of the stereotype over time have offered mixed results, with various methodologies counting anywhere from single digit percentages to 45 percent of recent graduates as "underemployed." But most have found that some people will always be what economists call "underemployed," and that the proportion of Americans in that position stays relatively constant over time.

For students and parents, having a graduate take a job that might appear beneath his or her qualifications might beat the alternative in an especially tight job market.

But a study released today by the labor market analytics firm Burning Glass Technologies suggests that graduates who take such jobs pay a lasting price.

Bachelor’s degree graduates whose first job does not require a bachelor’s degree (which is how the study defines the underemployed) are significantly likelier than those whose first job did require such a degree to still be underemployed five years later. (Many of those workers remain underemployed by this definition 10 years after leaving college.)

As is true of so many overarching statistics like this, enormous variation occurs among the graduates. Degree holders in many science and technology are less likely to be underemployed – and notably, women are quite a bit more likely than men to face that fate: 47 percent of them are underemployed, versus 37 percent of male graduates, found the report, "The Permanent Detour: Underemployment’s Long-Term Effects on the Careers of College Grads."

The data in the Burning Glass report, which was done in conjunction with the Strada Institute for the Future of Work, are likely to be seized on by the growing number of people questioning the value of a bachelor’s degree, and by extension the wisdom of college-going generally. (Some analysts said they believe the data and the report's conclusions from them overstate the extent of the problem and the reasons for it -- more on that below.)

Matt Sigelman, Burning Glass’s chief executive officer, says the data suggest that “there are too many schools producing bachelor’s degrees that are not taking into account the last-mile skills graduates need to get a good job, and too many graduates getting bachelor’s degrees that aren’t aligned with the job market.”

But the report’s findings do not suggest a “throw the baby out with the bathwater” problem, Sigelman said, because the difference in the capabilities and skills of “the employed and the underemployed is not necessarily a big gap.”

By being “a bit more mindful about” how to prepare their graduates for a first job, many colleges and universities should be able to “layer more preparation on top of the traditional education they offer," he said, preparing their graduates better for today's workforce.

Defining Underemployment

Everyone knows what unemployment means, and why it's a problem for the individuals involved. But underemployment is a murky term.

The federal government doesn't formally calculate underemployment in its regular surveys of Americans' working lives, largely "[b]ecause of the difficulty of developing an objective set of criteria which could be readily used in a monthly household survey," the Labor Department explains. (In other words, underemployment is too hard to measure accurately.) But scholars have typically mined federal and other data to try to define underemployment as being in the labor force but employed either at less-than-full-time jobs or at positions that don't match workers' skills and training or meet their economic needs.

Estimates of underemployment for recent graduates are often pegged at between a third and 45 percent, although a 2015 study by the Georgetown University Center on Education and Workforce -- defining underemployment as "those who want a job but don’t have one as well as those who want a full-time job but only have a part-time job" -- found rates much lower, even in the single digits.

Burning Glass mined its distinctive database of online job advertisements and résumés to define underemployment according to how employers hire workers. The company analyzed job postings and defined as a "college-level job" any position for which more than half of job postings requested a bachelor's degree. Using that measure, it added dozens of job types (such as insurance adjustor, radiation therapist and paralegal) to the standard job lists used by the Labor Department, and excluded some others. (Burning Glass acknowledges that these shifts in employer expectations, known as "upcredentialing," could inflate the amount of underemployment revealed by the report.)

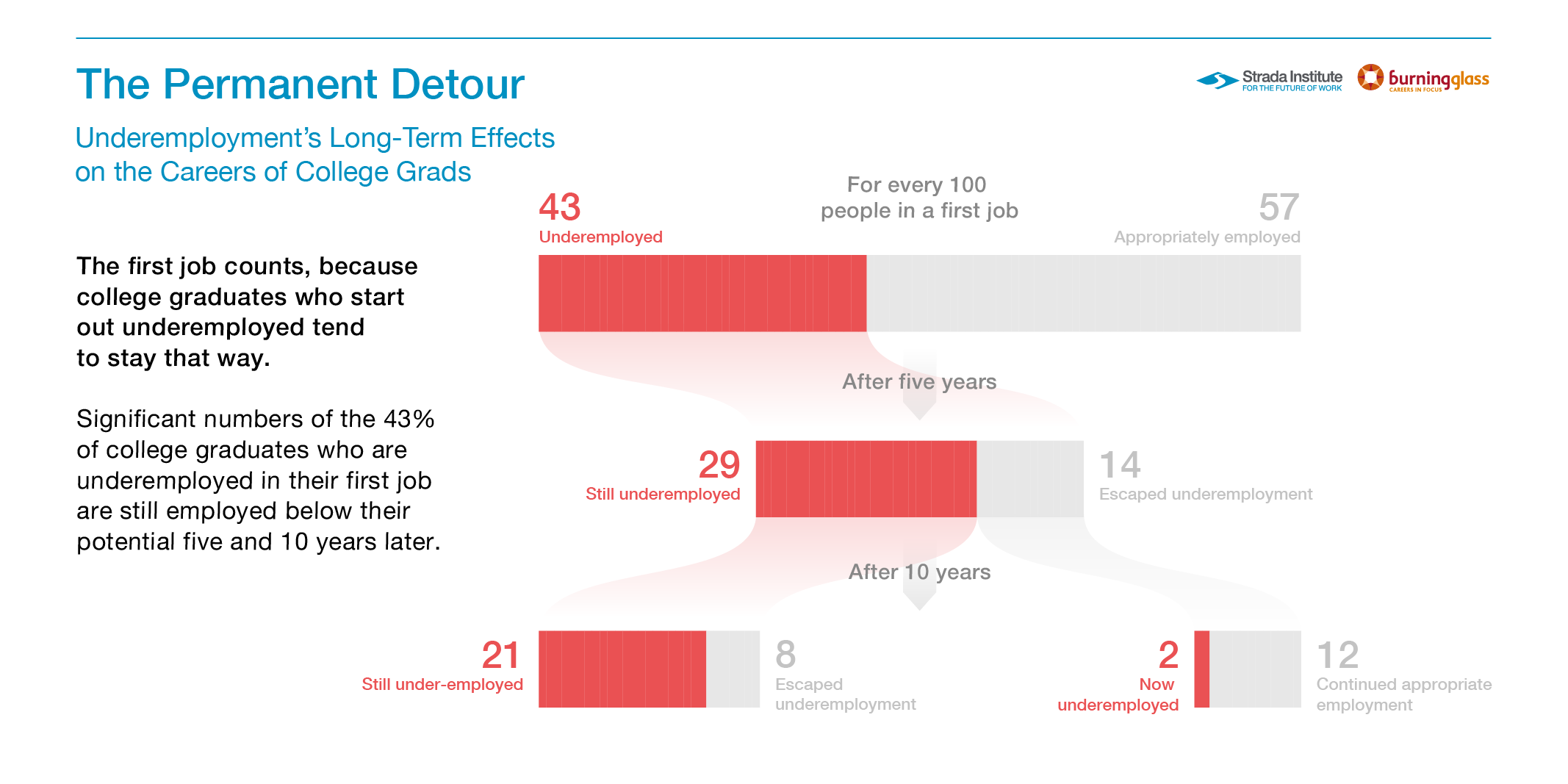

Using that definition, Burning Glass found that 43 percent of recent graduates had jobs that did not request a bachelor's degree, while 57 percent held positions for which employers sought workers with a bachelor's. The 43 percent who the company deemed as underemployed earned an average salary of $37,330, compared to the $47,470 earned by the majority who were appropriately employed.

The initial hole was tough to climb out of. Two-thirds of the 43 percent were still underemployed, by Burning Glass's definition, five years after graduating. And almost three-quarters of those were unemployed 10 years after they began their first job, as seen in the graphic below.

By comparison, the vast majority of the 57 percent whose first jobs were deemed "college-level" positions were in such jobs 5 and 10 years later.

Significant differences surfaced by major and choice of professional field. No surprise, but engineers (29 percent) and computer scientists (30 percent) were least likely to be underemployed in their first job, followed at a significant distance by communication majors (39 percent) and mathematics majors (39 percent). More than half of graduates in nine categories of graduates (including those majoring in psychology, general studies, biology and education) were underemployed right out of college. There was a similarly wide range of outcomes by job fields.

And strikingly, Burning Glass's analysis finds a large gender gap in underemployment. Nearly half of women (47 percent) are underemployed in their first job by its definition, compared to 37 percent of men.

These findings, the report says, "undercut a long-held assumption, that female underemployment is the result of work-life tradeoffs often expected of women.... While women are more likely than men to later slip into underemployment, what is most concerning is that women fall behind at the very outset of their careers, in their first jobs -- at the very point when, presumably, they have the fewest familial obligations."

"The initial job a younger worker takes can profoundly influence the direction of a long-term career," the report concludes. "Graduates who accept or are forced into subbachelor's-level jobs early in their careers suffer significant long-term consequences; they may be consigned to underemployment for years to come. The first job is a high-stakes decision, and both educators and graduates should treat it accordingly."

Questions and Critiques

Joseph Fuller, a professor of management practice and co-leader of the Managing the Future of Work project at Harvard Business School, said via email that the Burning Glass report "explodes the myth [that] a college degree is a golden ticket. The aptitudes and specific skills that students develop in a college program influence the arc of one’s degree, not merely degree attainment."

He also noted that while the so-called STEM fields rise to "the top of the heap" in Burning Glass's findings, "other skills, like communications, that employers often find in short supply are also rewarded."

Not everyone is convinced that the situation is as dire for recent graduates as Burning Glass portrays it to be.

Nicole Smith, a Research Professor and chief economist at the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, questions Burning Glass's decision to judge which jobs are "college-level" based purely on the fact that many employers are asking for (not even requiring) a bachelor's degree. "Employers can ask for everything under the sun, especially in an employer’s market," she said. "They assume that employers are actually going to hire based on that.... I care about what the person has who actually gets the job, who actually seals the deal."

Letting employers' desires dictate which positions get characterized as "college level" -- and treating as "underemployed" everyone who doesn't get one of those elevated jobs -- "would by definition result in higher levels of underemployment," Smith said.

In addition, she says, the analysis fails to account for the "voluntary" nature of some of what Burning Glass paints as forced underemployment. Some of the workers the analysis assumes to lack skills or preparation for the workforce may just lack the motivation; others may choose to work in a lower-stress position, in a "caring" profession, or to sacrifice a better job to stay near family or a loved one.

And even right out of the gate, she said, "women still bear the burden of child rearing," so for the age 22-27 group in the Burning Glass analysis, some may be choosing one job over another for that reason.

A 2016 study by economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found roughly similar levels of recent graduates to be underemployed, even though it defined jobs as "bachelor's level" based not on whether at least half of employers asked for candidates to have that degree, but because at least half of people in the positions said the degree was necessary to do the job.

But as Smith suggests, the New York Fed researchers concluded that many of the 40-some percent of recent bachelor's degree graduates who took jobs typically done by people without such degrees actually fared quite well.

"[C]ontrary to popular perception, our work reveals that most of these newly underemployed workers were not forced into low-skilled service jobs. In fact, many of the jobs such graduates took, while clearly not equivalent to jobs that require a college degree, appeared to be more oriented toward knowledge and skill when compared to the distribution of jobs held by young workers without a college degree," wrote Jaison R. Abel and Richard Deitz.

Abel's and Deitz's analysis also found that while some number of recent graduates did stay "stuck" in true underemployment, many others moved into jobs they were satisfied with, especially over time. Their assessment might challenge the use of the word "permanent" in the Burning Glass report's title to describe the impact of graduates' early stumbles.

***

Follow me on Twitter @dougledIHE.