You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Julie Libarkin is a passionate advocate for women in academe, specifically their right to study and work without being sexually harassed or assaulted. She’s also a scientist who loves data.

So two years ago, before much of the country had heard the words “Me Too” in reference to sexual misconduct, Libarkin began to meticulously collect information on -- and, most significantly, the names of -- publicly documented harassers.

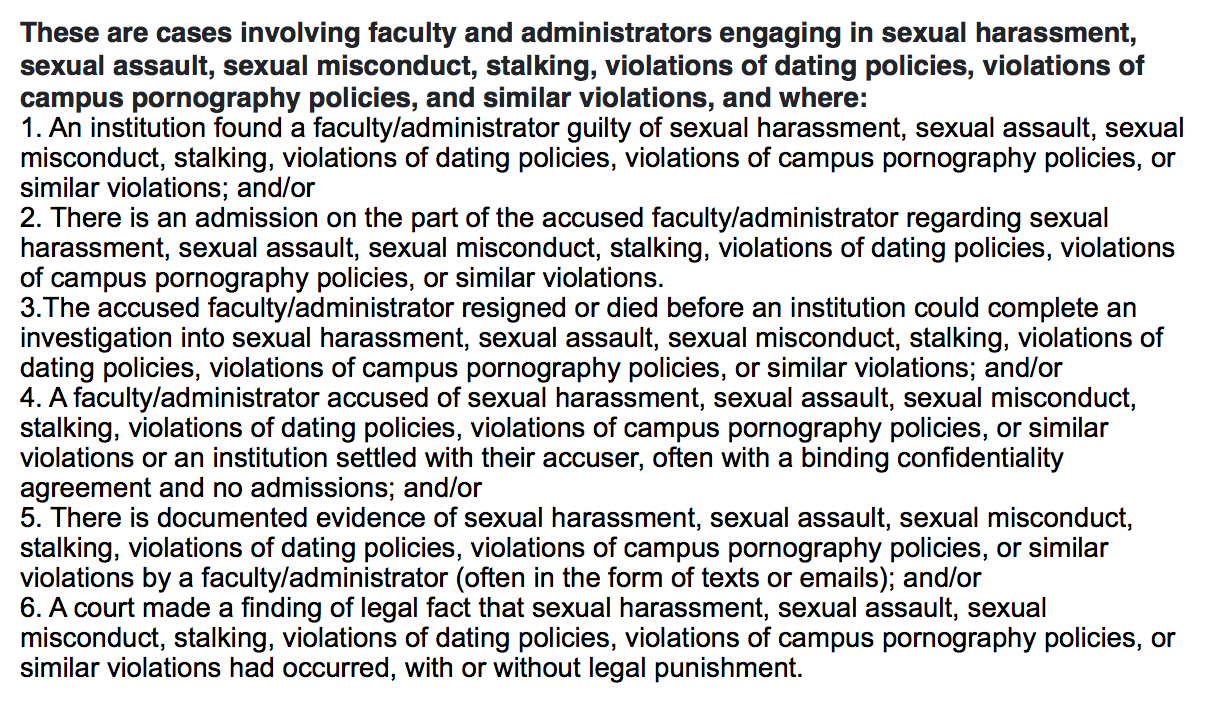

Her list of more than 700 cases differs from others created in the Me Too era in that it includes only substantiated reports, based on strict criteria, including institutional findings and admissions of misconduct, settlements between institutions and accusers, and legal findings of fact. Cases where the accused resigned or died during an investigation also are included. This is not a “Shitty Media Men” list for academics, though the men (and the significantly smaller share of women) on it have done shitty things.

“This is a lot of work. I spend hours a week on this," Libarkin said. "But I'm trying to make the hidden visible."

Still, Libarkin is frustrated by all that remains invisible: it’s well-known that most sexual misconduct goes unreported, and much that does get reported doesn’t make it to the public sphere. So strict are Libarkin’s research parameters, both out of scientific integrity and a fear of possible legal action against her, that she won’t publish cases she learns about from institutional paperwork handed over to her by accusers -- at least not without requesting and verifying it herself through open-records channels.

“This is very biased sample,” Libarkin said of her list, cautioning against drawing hard conclusions from it, thus far. Additional research is in the works, however, to try to get a "clearer picture of the nature of sexual misconduct in academia. We often say that sexual harassment is mostly perpetrated by men and towards women, but this sample provides empirical data to begin to let us understand gender makeup more deeply." Libarkin said she and a colleague also are interested in determining "whether or not consequences for misconduct are far-reaching, or if those who engage in sexual misconduct are able to move on to positions of power," receive awards, or more.

Given that many academic harassment conversations focus on unwanted attention or contact by faculty members, Libarkin did note that her list includes high-ranking administrators. There are also staffers for sexual harassment and assault compliance offices, gender studies professors, and those who “are supposed to know better.” She observed that some cases go beyond common conceptions of harassment, to involve stalking, murder and suicide.

“This started as an advocacy project. I was really just researching and documenting cases, and within days and weeks it just kept growing,” she said. “And as I was looking for sexual harassment, I realized there’s a whole category of behaviors that we understand as misconduct, from violation of pornography policies to stalking. Sexual misconduct is this umbrella term, so I came up with a research protocol for exactly what to look for.”

Source: Julie Libarkin

Along with legal announcements, Libarkin relies heavily on news stories to build her database. Yet she began the document mostly due to annoyance at the news media and its tendency to cover misconduct as what she described as “one-offs” at “institutions that are deemed special for some reason.”

Every once in a while Libarkin reads a piece about whether a particular discipline has a “problem,” she said, while the reality -- both publicly documented and based on experience -- is that harassment happens across fields, too often.

“These cases are presented as unusual,” she said. “But they are not unusual.”

Those observations are similar to what Karen Kelsky, a former tenured professor and founder of The Professor Is In, found in her massive crowdsourced document of harassment in academe. That database does not include names in most cases, and many reports are unsubstantiated.

Misconduct is not new: Libarkin’s database includes a recently documented case from 1917. She also noted there was surge of public cases in the 2000s, when there was a rising consciousness about harassment. Nowadays, she said, reports surge when there are public-records requests.

Libarkin said she’s received mostly positive feedback about her spreadsheet, which 89 people were reading late morning on Wednesday. Some of the responses are “traumatizing,” she said, recalling how a colleague pressed his pelvis into her back at a work-related party in 2010 -- the first day in a year she’d worn a dress, out of fear of something like that happening. She later reported the incident, but as the professor already was emeritus, the consequences were, to her mind, few.

That professor's name is not incuded in the document.