You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

There’s a lot of chatter about faculty diversity statements, good and bad. But there’s little talk about what’s actually in them. Do they all read the same? Do they provide a clear record of faculty applicants’ past efforts to promote diversity, equity and inclusion in their teaching, research and service? Or do they focus -- less helpfully, in critics' eyes -- on faculty applicants’ beliefs about diversity? A new working paper from researchers at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor's National Center for Institutional Diversity attempts to inject some substance into the conversation.

“From the thousands of applications my team and I have read” for this paper and other work, said co-author Tabbye Chavous, center director and professor of education and psychology, “applicants were not just submitting statements of political beliefs or ideologies.” While statements vary in detail and depth, she continued, “applicants were writing about their experiences, accomplishments and goals as they relate to the faculty role, suggesting the benefit of telling applicants what we're looking for -- rather than them trying to figure it out and then feeling pressured to fit themselves into what they think we’re asking for."

Chavous’s paper, recently presented at the annual meeting of the Association for the Study of Higher Education, is an analysis of faculty equity, diversity and inclusion statements required of applicants to a postdoctoral fellow-to-faculty program across dozens of disciplines at Michigan’s College of Literature, Science and the Arts. Some institutions now require these statements across departments, but the requirement varies by program at Michigan.

The sample size for this particular paper is small: 54. But the researchers sought to create a helpful typology that would shed light on what contributions to diversity candidates were actually highlighting in their statements. Ultimately, they found seven recurring elements: "values and understanding" of diversity, equity and inclusion, along with teaching, research and scholarship, engagement and service, mentorship, skill building and personal growth, and personal background experiences.

The authors also considered qualitative features of these statement: depth of discussion and engagement, and the sphere of influence or impact of the actions described.

Again, the authors didn’t test a theory about diversity statements, they wanted to develop one -- hence the typology. Regarding values and understanding of diversity, equity and inclusion, applicants often included statements of support for advancing these values, or described their understanding of structural issues that impact them on campus and off. Valuing diversity and clearly understanding it weren’t always linked in these statements, the authors note. But they often were.

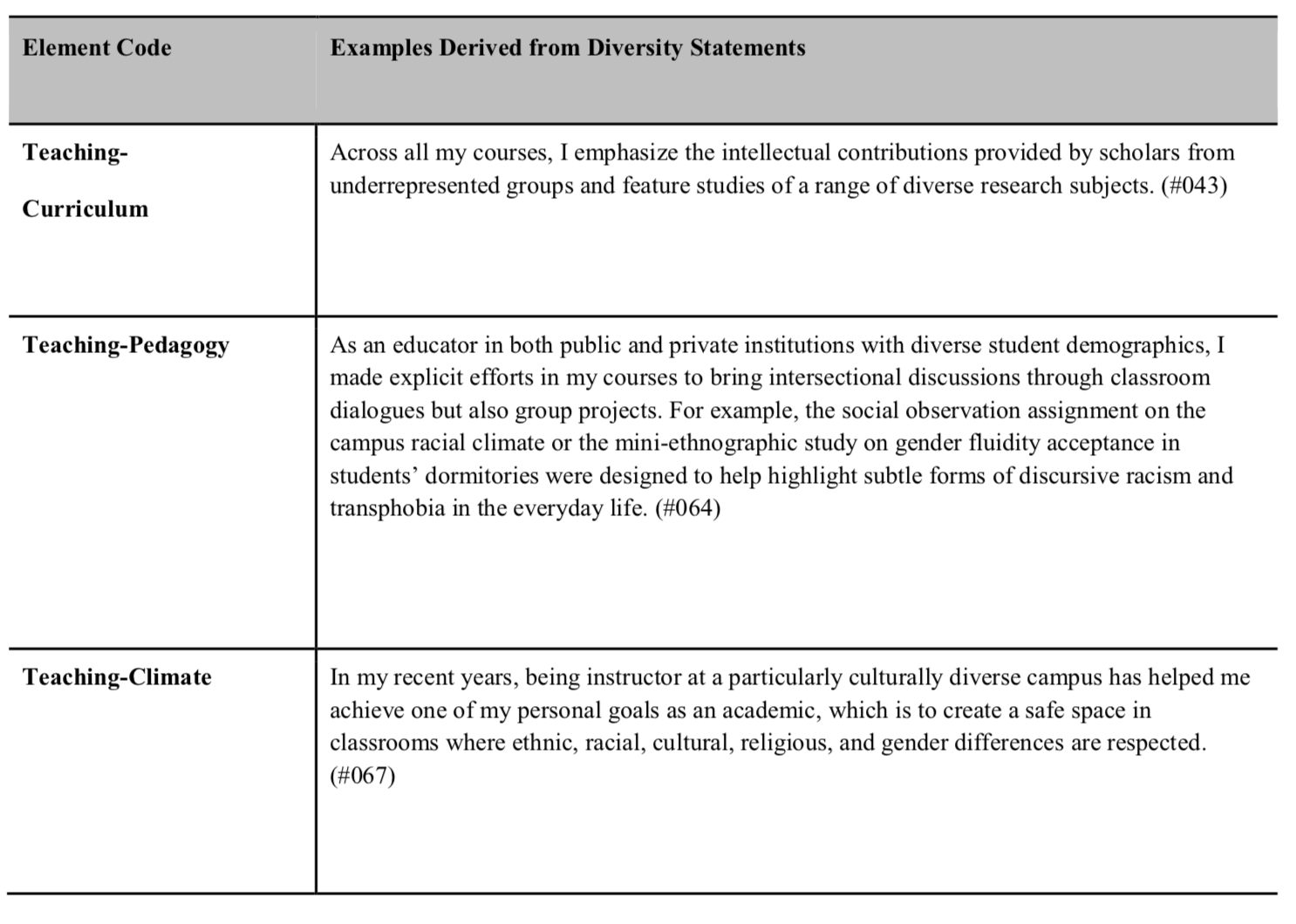

Regarding teaching, applicants often talked about advancing diversity, equity and inclusion through course curricula, such as accommodations for students within syllabi or course readings from underrepresented scholars. Statements also included discussions of pedagogical practice (discussing diversity with students or making space for all students to participate, for example), or the promotion of inclusive classroom climates.

Source: National Center for Institutional Diversity

Teaching and the classroom space were mentioned 80 times across 39 statements analyzed in one phase of the work, with pedagogy being discussed most often. Many applicants referenced the growing body of literature on fostering equity and inclusion.

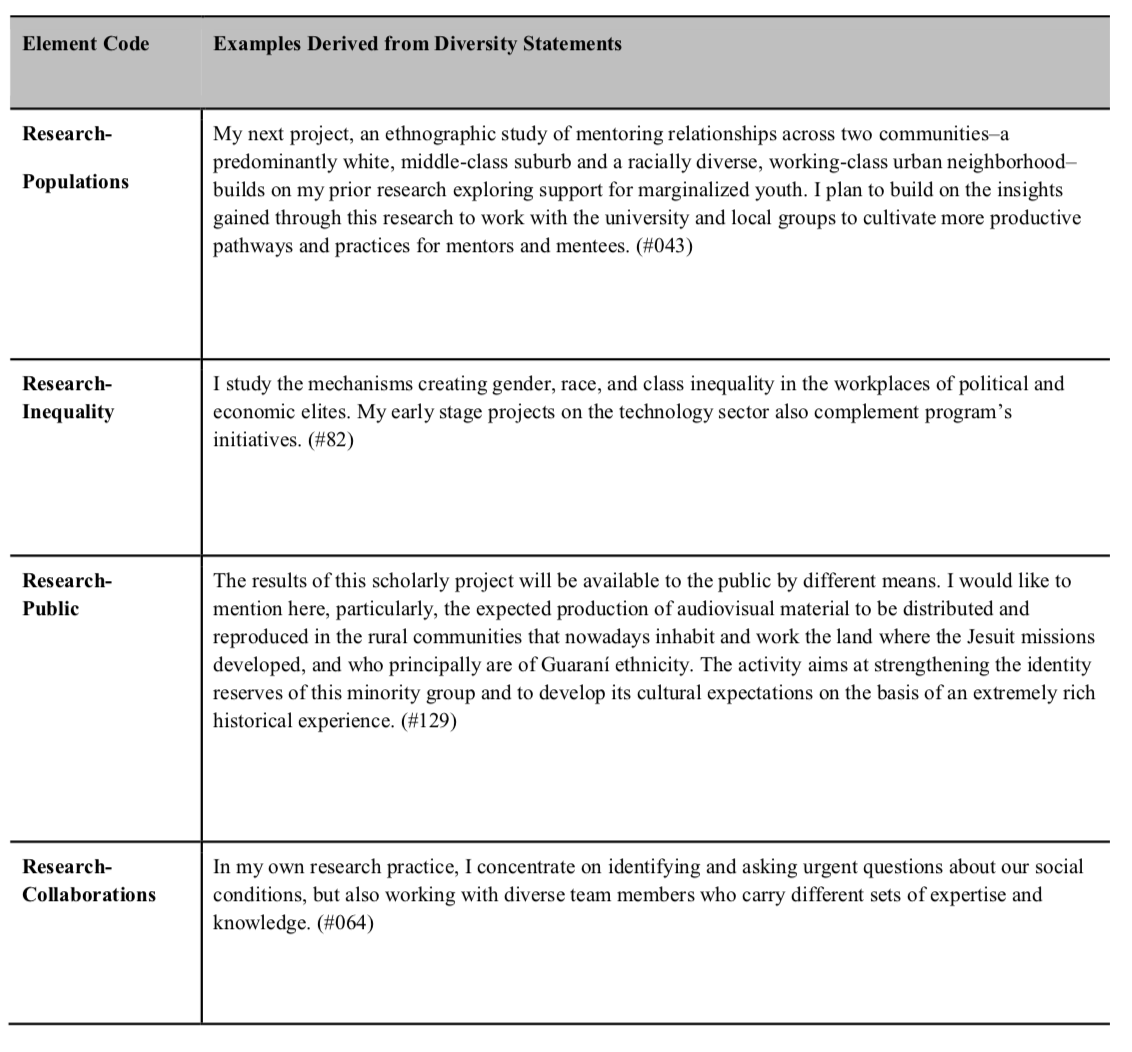

Scholars referenced their research and scholarship 70 times over the 39 statements, but their foci varied. And sometimes those who did research on underserved groups or inequality didn’t recognize that work as related to diversity, equity and inclusion, Chavous said. That underscores the authors’ assertion that diversity, equity and inclusion work happens all the time -- often by underrepresented scholars -- but that academics aren’t used to talking about it: it’s what the literature calls “invisible labor.”

Chavous said that the postdoc-to-faculty program in question sought to conceptualize the work of diversity, equity and inclusion as “involving skills and competencies that enhance the capacity of institutions to provide … environments that are intellectually rich and inclusive.” And that is a “needed departure” from views of diversity work as “service add-ons,” or as political to ideological, “toward a conceptualization of diversity as interconnected with excellence.”

Diversity statements also included efforts at public scholarship, promoting diversity work in nonacademic channels. Applicants also mentioned efforts to promote diverse research teams.

Service contributions included efforts to develop institutional policies or practices. This most often manifested as participation and involvement in organizations, programs, projects or professional organizations.

References to applicants’ engagement and service were identified 80 times across the sample, with most describing engagement in organizations or programs, as opposed to explicit policies.

Mentorship, which has remained underrecognized across academe, included the mentoring of individual students from underrepresented populations and serving as a mentor within a mentoring or pipeline program. Skill building and personal growth was the least common type of contribution. But applications did mention attempts to increasing their diversity-related competencies, both through formal and informal processes.

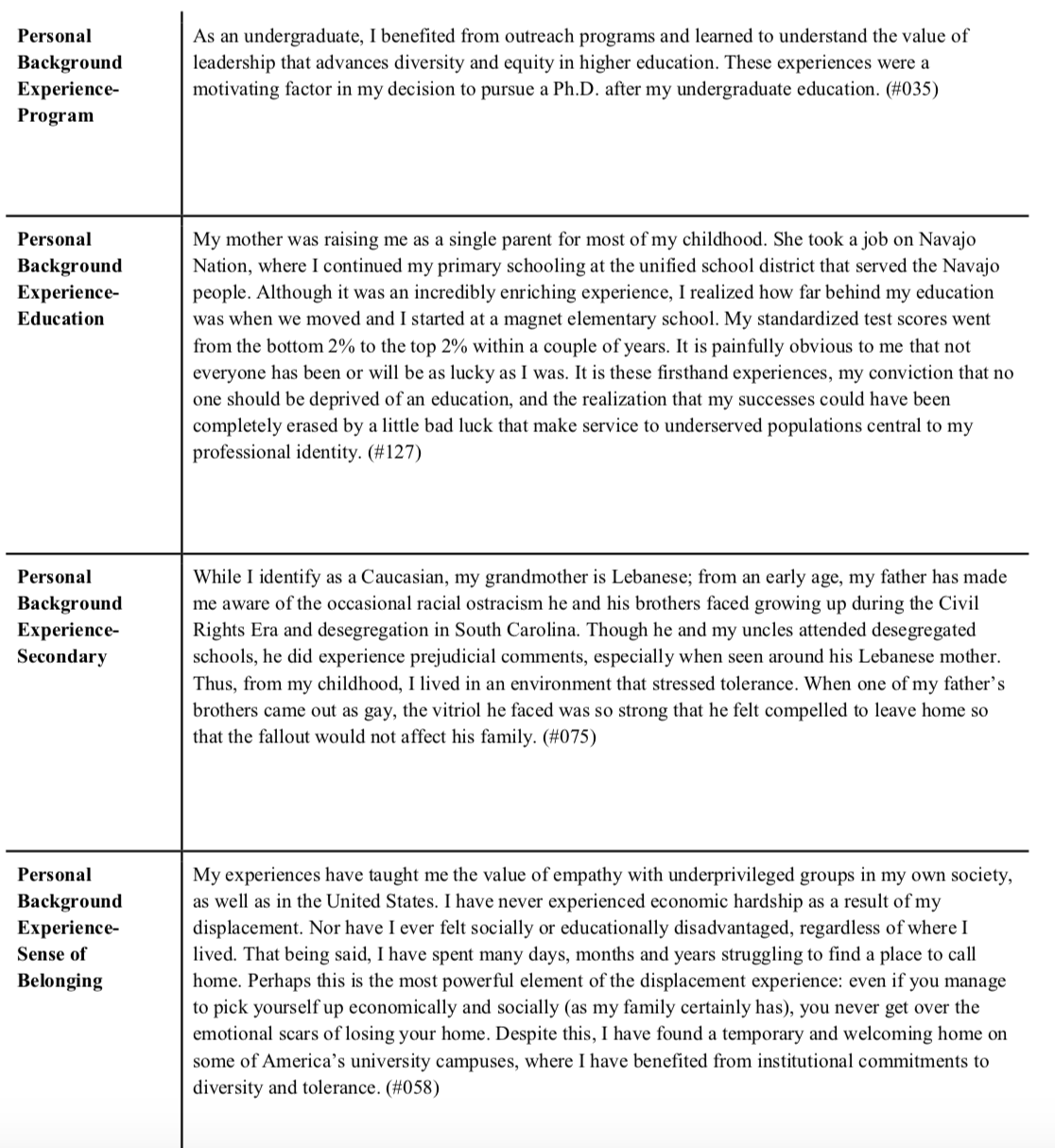

Personal background experiences centered on personally held identities, backgrounds and experiences of applicants and how they shaped their perspectives, behaviors or actions. Chavous said she doesn’t necessarily recommend that her own mentees disclose their underrepresented identities in their application portfolios, and that it’s a personal choice. But applicants in the sample disclosed a range of identities, or multiple identities, from ethnicity to gender to socioeconomic status to nationality.

Here are some examples included in the study:

When applicants mentioned frequency of engagement, they were typically “one-time” or “sustained” experiences. When articulating the different ways that they fomented change, applicants often did so through passive proposals, concrete proposals or adopted actions. And when describing the role that they played in these events, the applicants tended to describe themselves as what the study calls “active participants” or “leaders.” Interactions were either one on one, affecting policy, or with an audience.

Over all, Chavous said that scholars across disciplines “were able to describe many ways that their work in scholarship, teaching and mentoring, and service and engagement represented their demonstrated commitments to diversity, equity and inclusion.”

Their statements also reflected “many different ways of defining and thinking about diversity,” Chavous said. In other words, there was “no one type of diversity statement or single way of engaging diversity seriously and effectively.” That’s important to note “in the context of criticisms that institutions asking for diversity statements are looking for particular profiles, ideologies or expressions of values.”

Indeed, some critics continue to question whether these diversity statements threaten academic freedom, or push one’s research and teaching in a certain direction for fear of not otherwise being hired. Chavous said she and her team have just begun looking into how these statements are actually being used in hiring decisions (that was not part of the recent paper). But, in the interim, she described asking faculty candidates to submit statements about how equity, diversity and inclusion factor into their teaching, research and service as exercising truth in advertising. It doesn’t quite make sense to affirm diversity as underpinning the institutional mission, while not giving candidates the opportunity to talk about and be credited for their efforts, she said. To that end, diversity statement guidelines for these candidates should be as transparent and direct as possible.

“Too often in higher education and other organizations, diversity is understood as only a proxy, or code, for race or demographic identity, and it is often not tied to equity and inclusion,” Chavous said. “For the faculty program from which we drew our data, applicants were provided explicit guidance about the goal of the diversity statements -- that the university was looking for indicators of demonstrated commitments to diversity, equity and inclusion and valued the different ways this might be demonstrated,” such as scholarship, teaching, mentoring, service and engagement.

“We have more work to do in this area,” Chavous added. “But I’m pushing back on the idea, ‘We shouldn’t be asking about this, because it’s ideological and we should be looking at objective information.’ But there is so much research indicating that how we assess faculty work in general relies on a series of assumptions of objectivity -- from reputations about networks and who trains scholars and what journals they publish in. These things are all based on consensus.”