You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

Students benefit from increased faculty engagement. Yet many professors still resist more student-centered teaching.

Part of the problem is that graduate schools are slow to adopt pedagogical training, meaning that some professors may want to up their interaction with students but don’t know how. Another part of the problem is that becoming a better teacher takes time, an increasingly scarce faculty resource.

What if engagement wasn’t complicated and didn’t take that much time? Preliminary research called "My Professor Cares: Experimental Evidence on the Role of Faculty Engagement," presented last week at the annual meeting of the American Economics Association, suggests that even “light touch” interventions can make a difference to students.

“Everything we know from K-12 education is that teaching matters,” said co-author Michal Kurlaender, professor and chancellor’s fellow in education at the University of California, Davis. “Yet somehow we’ve left the college classroom alone. We have wraparound services for students, but the classroom space is considered sacrosanct and faculty can do whatever they want. We wanted to interrogate that by having faculty members provide some simple, individualized feedback to students as an intervention.”

Kurlaender and her co-author on the project, Scott Carrell, professor of economics and co-faculty director of the California Education Laboratory at Davis, wanted to see what would happen if professors reached out to students individually via email just a few times a term, with the goal of promoting their sense of self-efficacy and help-seeking behavior. Would their performance improve? Would they get a better impression of the course and the professor? A small 2014 pilot study involving economics students at Davis suggested yes, to both.

After the first email “nudge” about homework, students in the Davis study increased the time they spent on homework. After a second nudge about performance on their first course exam, students scored significantly higher on a second exam, compared to students in a control group who did not receive the emails.

There was no significant positive effect on overall course performance or on course withdrawals. But students reported that they appreciated the intervention.

“[I’d] like to thank you for offering your help in such a kind manner, I've rarely seen teachers at this school respond to missed assignments the way you have,” one student responded to a professor, for example. "I’ll be sure to complete future assignments in a timely manner, the first practice homework was indeed pretty helpful.”

Another Setting

Would the intervention work across a more access-oriented institution, however, where persistence rates are lower and students are arguably in greater need of faculty engagement? Kurlaender and Carrell designed a bigger study involving dozens of disciplines, from art to math, at one unnamed campus in the less selective California State University System.

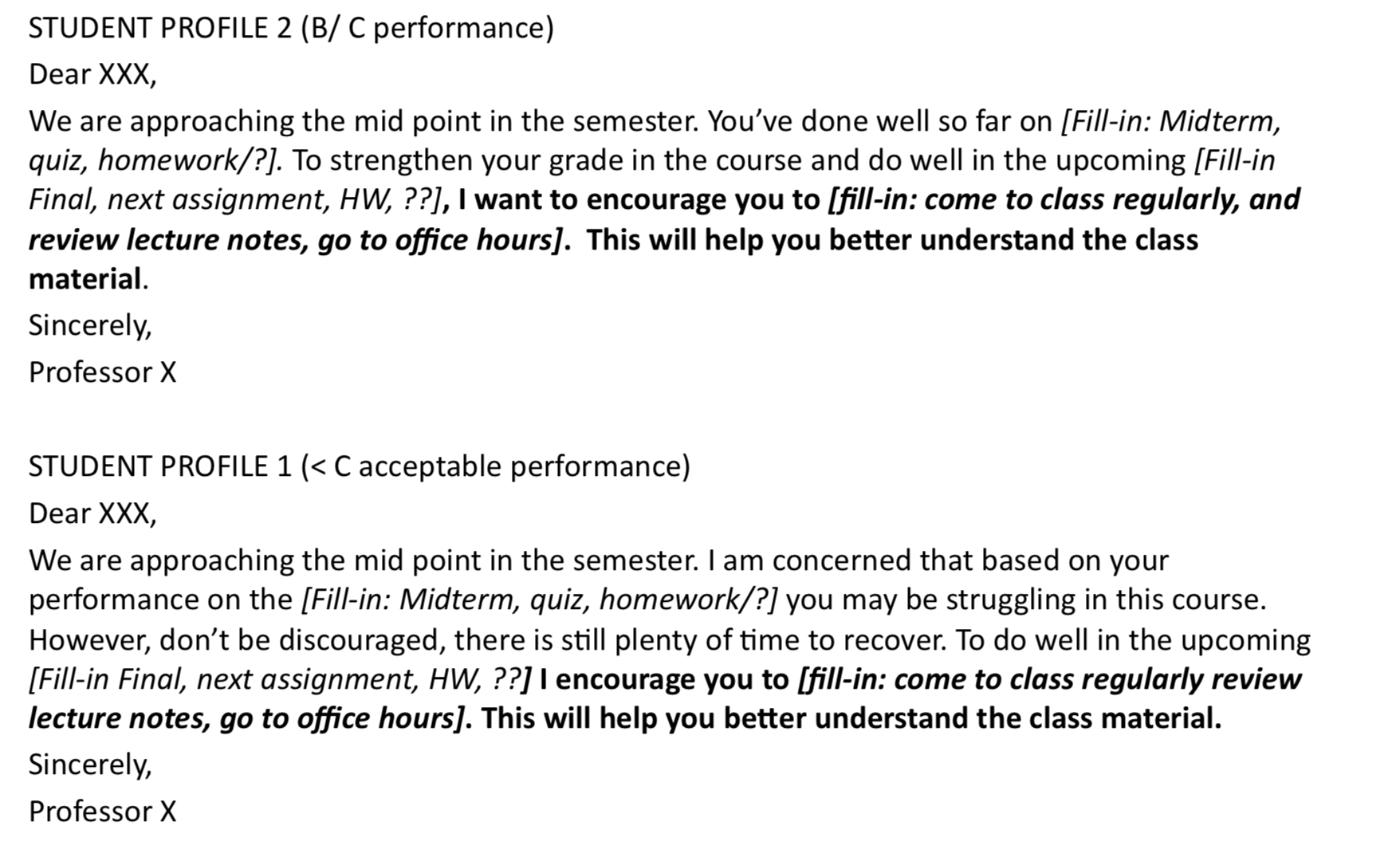

Compensating participating professors for their time with $500 each, the researchers directed these instructors to send three different kinds of emails to students in their courses over a semester. The first was a welcome-style email, sent two to three weeks into the term. The second offered feedback on performance halfway through the semester. The third was sent about a week before the end of the term and final exam.

In all three emails, the idea was to offer feedback and information about course performance and success, focusing on the underlying processes involved in completing course tasks and offering strategies to improve performance.

Crucially, Kurlaender and Carrell wanted professors to focus on positive steps their students could take to improve their performance, rather than on shortcomings. Professors received templates for each kind of email, which varied by student performance. Below are some examples.

Source: Kurlaender and Carrell

In spring 2016, half of the students in 24 courses at California State were randomly assigned to the intervention group -- some 1,134 in all. The rest, some 1,218, made up the control group and did not receive professors' personalized emails.

A modified study design, involving about 1,600 additional students, was adopted in fall 2017.

In response to professors’ emails, some students expressed alarm at being contacted directly by a professor. “I was wondering why I was sent this message,” one student wrote to a participating art instructor. “I believe that I have been coming to class regularly as well as taking notes actively. Thank you for your time.”

But many others were more welcoming, or expressed appreciation. “I attend every class, go to the review sessions, and have turned in the extra credit so I am defiantly [sic] trying to do well but I am still struggling,” one student replied to a history professor. “I will come to office hours and try to meet up with our TA as well. Let me know if there is anything else I can do. Thank you!”

Participating professors also were asked to complete a survey after the term about the intervention, for which they received a $100 Amazon gift card.

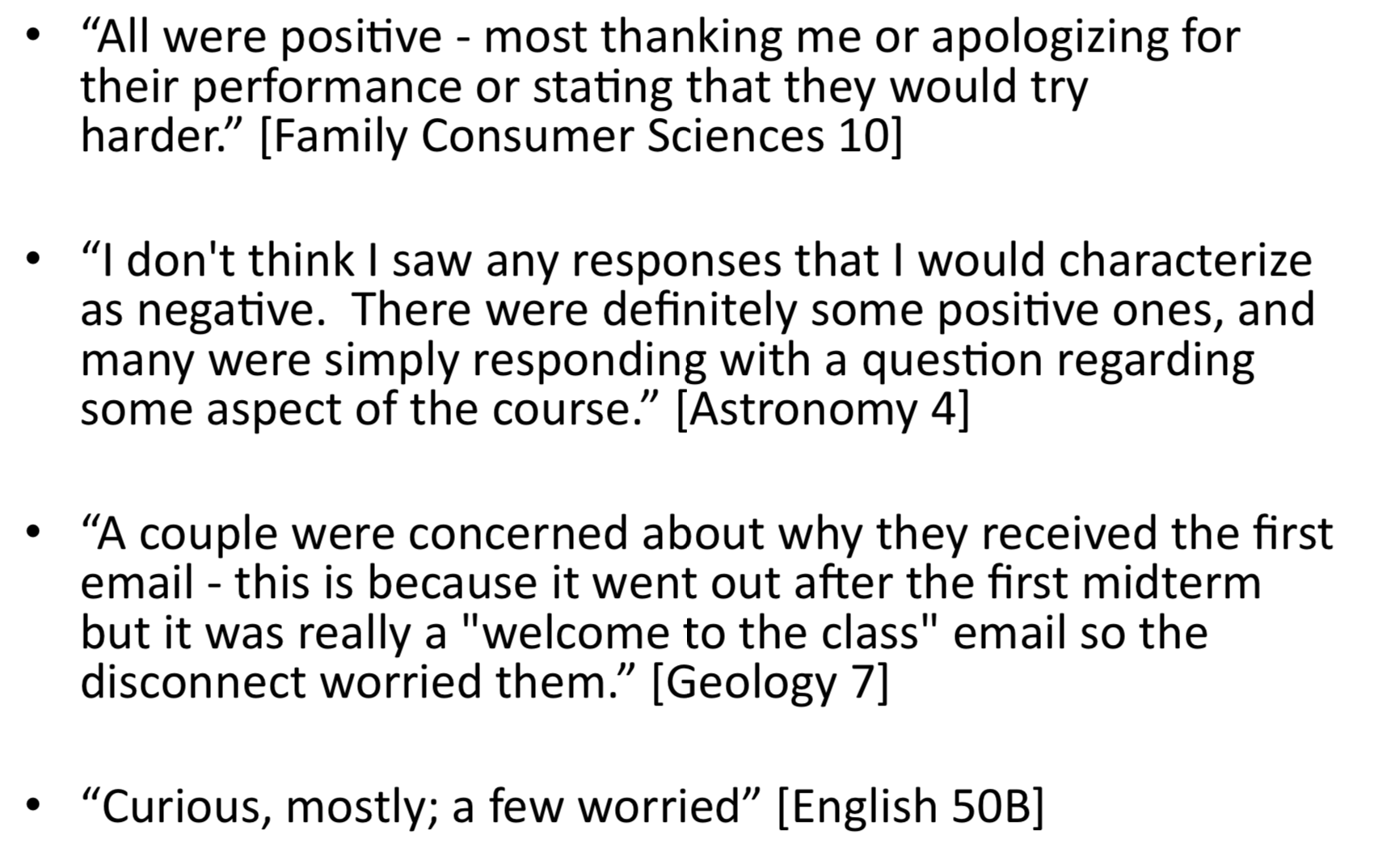

Here is how some professors described the nature of the student responses they received:

A number of professors said they were surprised by their students' gratitude at their gestures. Other professors said they found interacting with their students outside class to be important. But some said the intervention probably did more to highlight students who already were engaged, rather than hook those who weren’t.

Findings and Future Research

Over all, Kurlaender and Carroll found strong evidence that this "light-touch, targeted feedback" can positively affect student perceptions about a course and instructor. But in the California State study, unlike the University of California study, they found no evidence of the intervention's effects on course performance -- with one exception: students with fewer than 30 previous college credits seemed to have improved course performance after getting the emails.

Positive results on student perceptions of the course and instructor -- gauged by a student survey that asked questions about professors' availability and degree of caring -- were largely driven by Latinx, female, first-year students and more prepared students, based on high school transcripts.

Kurlaender and Carrell are still trying to figure out why their intervention positively affected student course performance on their campus and not another. They’re soon running a second, bigger Davis study to re-examine their initial results. But Kurlaender said the California State finding is not a reason to give up on student engagement at more access-oriented institutions. If anything, she said, the findings may mean that students need not just three emails per semester, but more -- or maybe even a required face-to-face meeting.

“Maybe this was too light-touch, but we wanted something scalable but that wouldn’t take too much time,” said Kurlaender, noting that professors said each email took just about one minute to send.

Either way, she said of faculty engagement, “This is an untapped space where we should think about moving the graduation rate.”