You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

Faculty buy-in is a common challenge to curricular innovation. But what about students? What hurdles, if any, do they represent when it comes to adopting a more student-centered pedagogy? After all, taking notes during a lecture is arguably less demanding than engaging in more active learning.

That question is at the heart of a new study published in PLOS ONE, called “Knowing Is Half the Battle: Assessments of Both Student Perception and Performance Are Necessary to Successfully Evaluate Curricular Transformation.”

Hypothesizing that student buy-in would increase as the share of students who completed a revised course grew within a given student population -- due to a new sense of “community,” and not just teacher efficacy -- the authors of the study measured learning gains and attitudes during a course transformation at a small liberal arts college.

Using an original curriculum called Integrating Biology and Inquiry Skills, or IBIS, the authors found that students reported and demonstrated substantial learning gains. And, confirming their original hunch, the authors determined that buy-in did increase with each successive cohort -- in part because students increasingly linked certain aspects of the course to their learning gains in surveys.

Suann Yang, an assistant professor of biology at the State University of New York at Geneseo, co-wrote the study with several colleagues. They helped develop the IBIS curriculum, which covers introductory biology in nine modules or scenarios that touch on real-world problems, such as diseases. Then the authors and other faculty members at the small college, which Yang has since left -- some 13 in all -- taught the courses to 724 students for four years.

Student resistance was highest the first year, based on pre- and post-course surveys. But by the end of the fourth year, it was significantly reduced. While students' overall course grades did not increase, substantial learning gains were observed across all years.

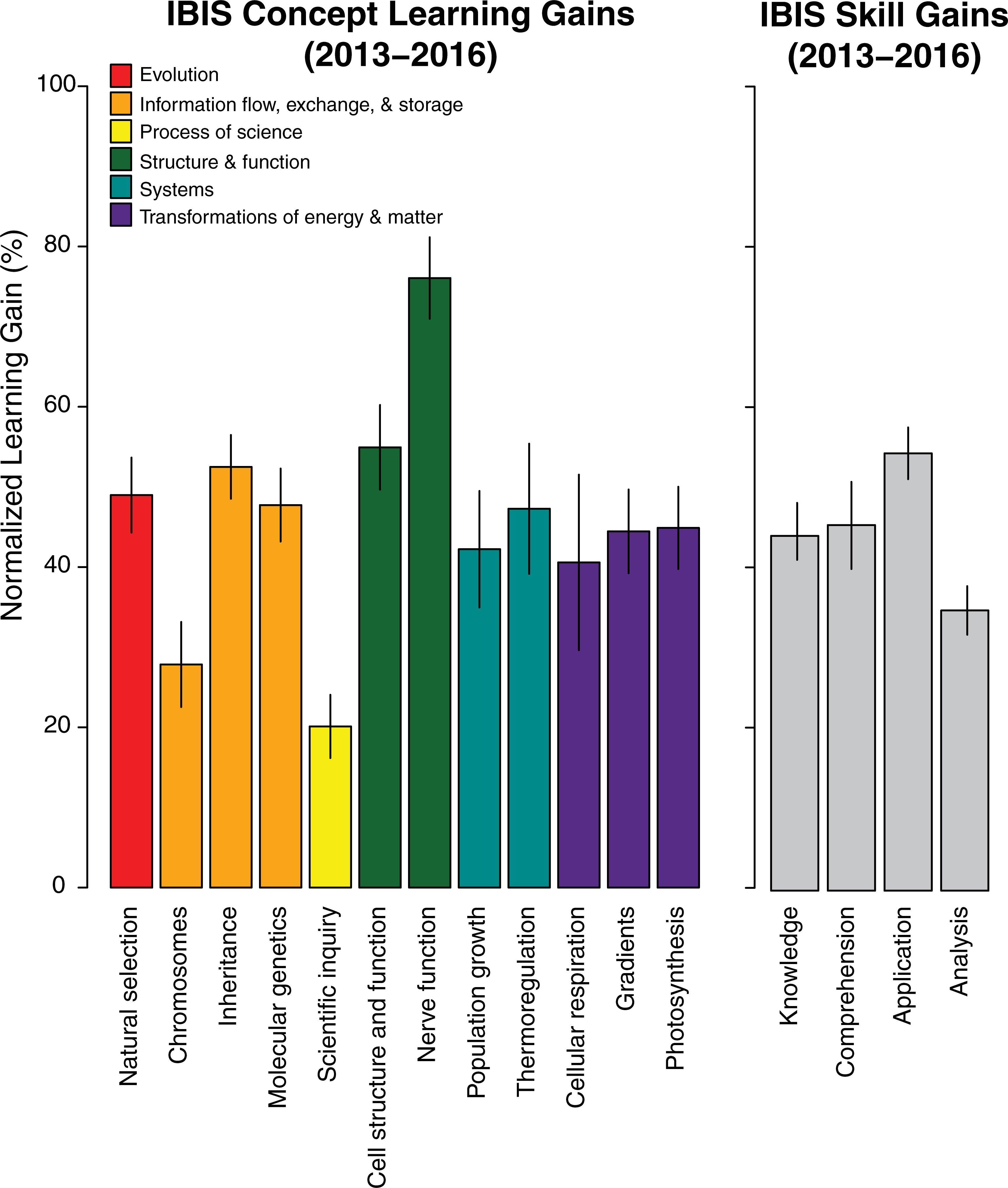

Students participating in the IBIS curriculum demonstrated learning gains of between 19 and 75 percent in terms of content knowledge and between 30 and 50 percent in terms of skills, based on several different instruments. That’s comparable to or exceeding reported learning gains from other student-centered environments, according to the study, "and help[s] to explain the extensively documented increase in student performance under active learning environments compared to traditional lecturing."

Source: Shaw et al. Note: Normalized learning gains across concepts (a) and skills (b) were above 19 percent across all years of the study.

Data collected at the same time on student attitudes show that the “increased frequency of students who have successfully completed the course in the student population promotes buy-in among current students,” the authors add. They also guess that their “thorough use of formative assessments and a well-structured peer mentor program -- major components of the IBIS curriculum -- may help students identify and correct deficits in their understanding of course material, which are key components of student metacognition.” Students most frequently identified "clicker questions," which help instructors gauge student recall and understanding in real time, as helpful. There was no observed difference in attitudes among science, technology, math and engineering majors and non-STEM majors.

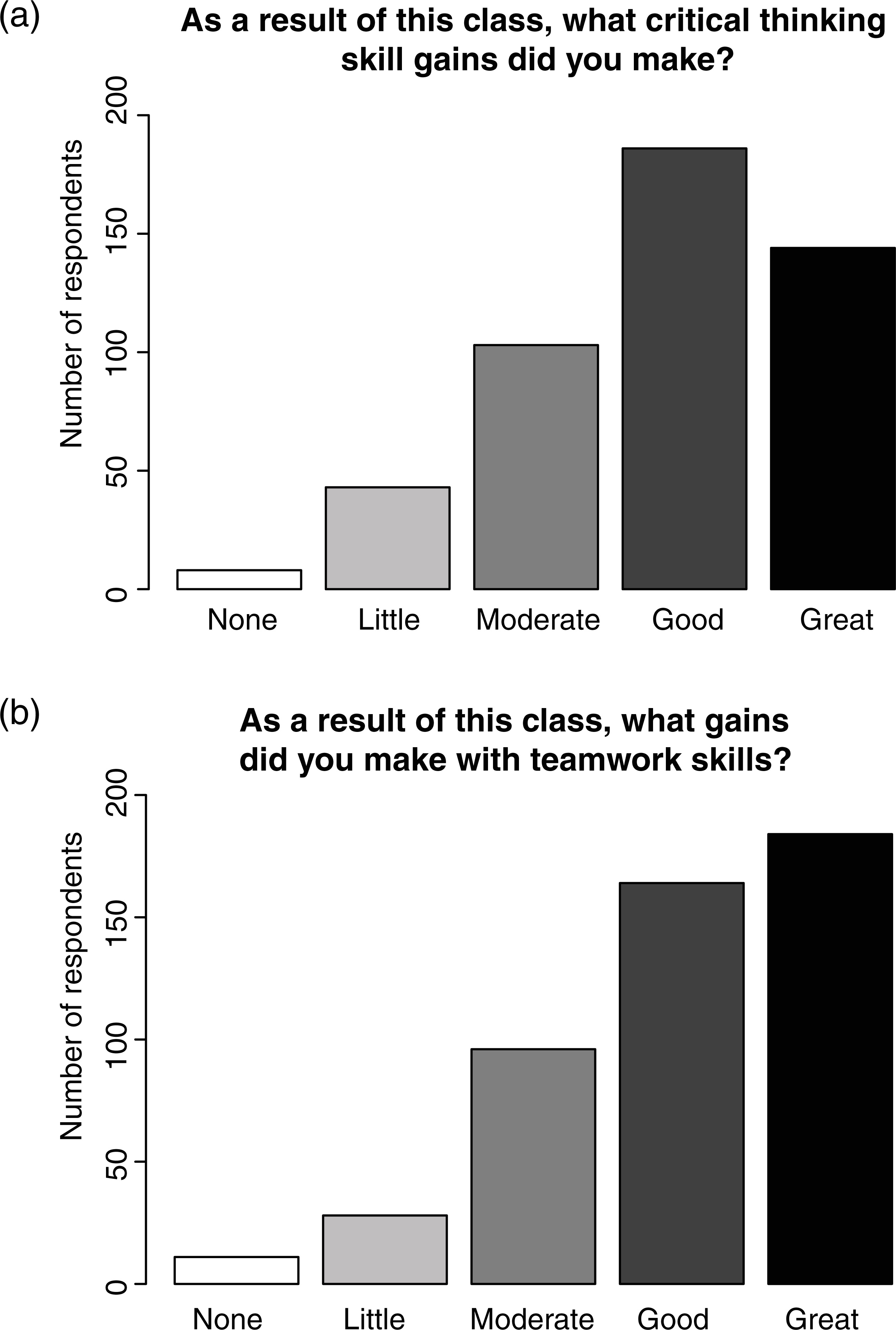

Note: An overwhelming majority of students, compiled across all years of the study (2013-2016), ranked their gains as moderate or higher in teamwork (a) and critical thinking skills (b) as a result of the course.

Interestingly, more students reported wanting to know more about biology before the course than after. But the study attributes this to possible factors other than the new curriculum, such as the fact that negative responses were largely driven by students who were not planning to major in STEM. Students also had increasingly positive responses over the years of the study to questions about how the class impacted their perceptions of biology.

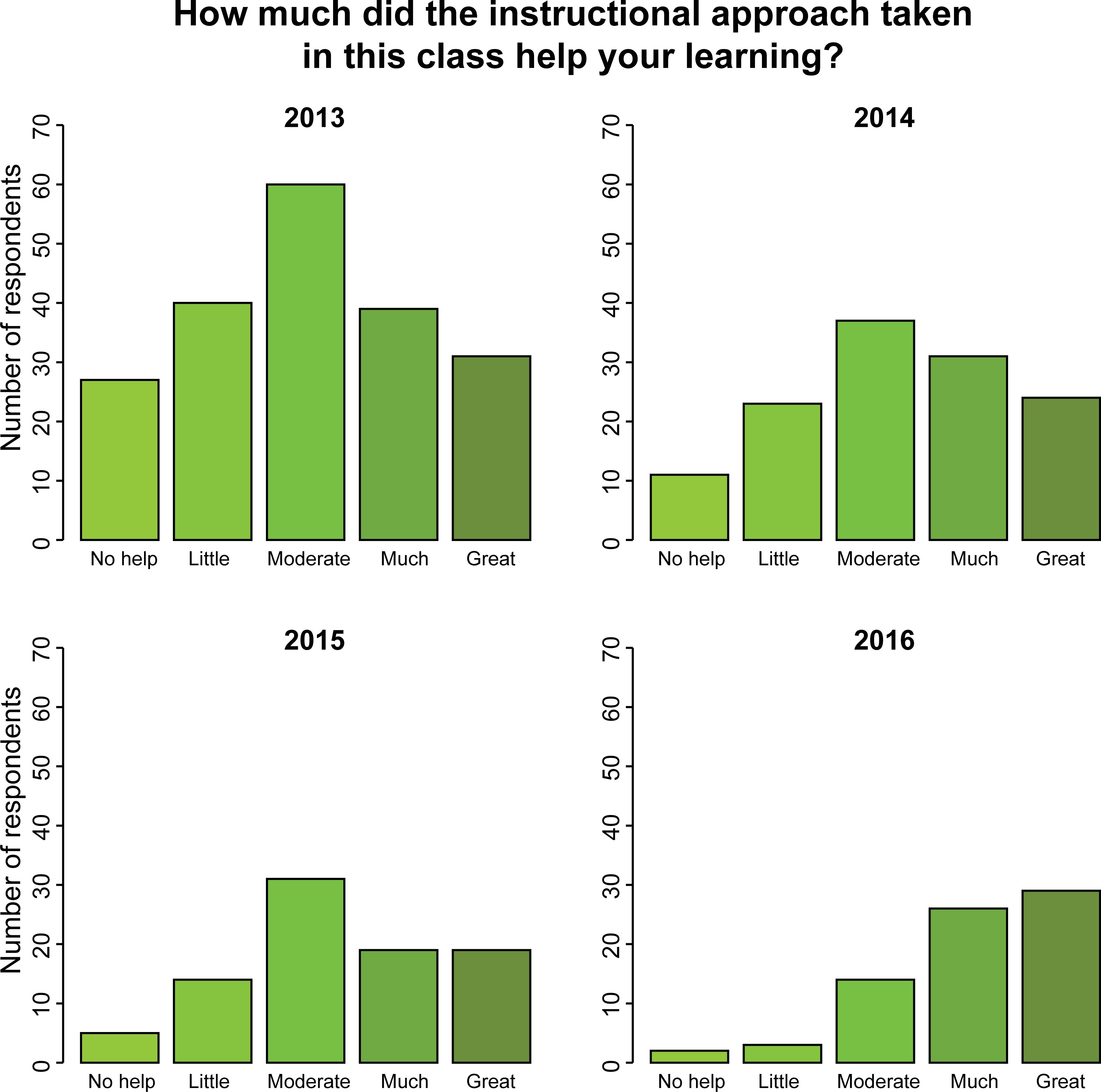

Note: Student responses shift over time, reducing the frequency of low rankings (No help, Little) relative to high rankings (Much, Great). Over four years, students increasingly report the instructional methods as responsible for large gains in their learning (p<0.0001).

Co-author Tarren J. Shaw, a lecturer in biology at the University of Oklahoma, said via email that while the main purpose of the project was to update a biology curriculum, “we were interested to measure the amount of student resistance to our changes, and figure out if there were any patterns in student resistance.”

As faculty members, he said, “we can be reluctant to make changes in the way we teach, especially if changes result in negative feedback from students on teaching evaluations.” And because institutions’ end-of-semester teaching evaluations aren’t typically designed for measuring resistance, he and his team used the pre- and post-course instruments to specifically gauge student perception of learning gains and which aspects of the course contributed to them.

“We found that there was surprisingly very little resistance from students, and that this resistance lessened every time we taught the course,” Shaw said. “This underscores the need for faculty and administrators to understand the time frame over which student buy-in to change occurs. Both patience and persistence are needed.”

As for faculty buy-in, Yang said that was a concern “because we needed cooperation among the many instructors of this team-taught course.” And while teaching the new curriculum was difficult at first, she said, having a cohort of faculty who supported one another during the transition was helpful.

“In fact, the curriculum’s success is probably due in part to the collaborative and collegial working group of instructors that developed during the project,” she said.

Still, Yang said, “it’s also important to recognize that student perspective can play a hidden role in the success of a course.” That’s especially relevant where active learning is concerned, she said, since “we need students to be on board and engaged for this type of instruction to be effective.”

Over all, Yang said she and her team recommend “spending some time at the start of the semester, and throughout the term, to [justify] the curricular change taking place.”

Kelly Hogan, associate dean of instructional innovation for the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, worked for years with students and faculty members on the campus’s Association of American Universities STEM initiative. The project involved adopting more highly structured active learning in introductory-level courses in four departments. And in her experience, student resistance is a factor in curricular innovation -- particularly among students who haven’t been exposed to active learning before, or when it’s been introduced and adopted poorly.

“If a professor tells students something like, ‘I’m trying a flipped classroom for the first time,’ and then it doesn’t go smoothly,” Hogan said, “students will resist that kind of pedagogy with the next instructor that uses it.” She and a colleague like to jokingly tell other professors, “Never say the F-word to students!”

More generally, Hogan said that when Chapel Hill began moving toward more student-centered learning, first-year students tended to accept it, while professors who tried it with their juniors and seniors found “it was much harder to get past their resistance.” Still, she said, students became more comfortable with the style over time.

“I knew we were making progress on the student perception side when I overheard a student walking along a campus path say to her peer, ‘Oh, don’t take that class, it is just a lecture,’” Hogan recalled.

She noted that the Chapel Hill AAU project also involved a lot of sampling of student perceptions in mid-semester surveys. Over time, instructors saw increases in how students valued active learning and actual learning gains on concept tests, along with perceptions of classroom atmosphere.

As for the new study, Hogan said it’s “an important read to professors and departments looking to make change in their pedagogy.” In particular, Hogan said it highlights how a variety of tools can be used to assess students longitudinally, including student perceptions.

“Because many faculty don't often have the flexibility to change the question in campuswide, end-of-course evaluation tools, the study serves as a nice road map for how individual faculty or departments could think about students holistically,” beyond just learning gains when assessing changes in pedagogy, she said.