You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Discrimination is a source of stress for many faculty members, especially women and ethnic minorities. And most professors say they’re not prepared to deal with diversity-related conflict in their own classrooms. So finds a new report from the Higher Education Research Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The institute publishes its survey of undergraduate teaching every three years, with this report covering 2016-17. The publication is a data trove on the faculty experience and includes additional information on professors' satisfaction with salary and benefits and mentoring students and other professors.

Teaching issues ground the survey. In response to a new set of questions this year, for example, most professors across disciplines said it is their responsibility to promote students’ ability to write effectively and to prepare them for future jobs and advanced education. But just about one-quarter of respondents said they strongly believe they should provide for students’ emotional development.

There’s additional information on faculty politics. And contrary to how they’re often portrayed in popular culture, professors aren’t all liberal. In fact, relatively fewer professors self-identified that way in this survey than in years past.

The institute weights professors' responses to most questions to get a nationally representative sample. Most results are based on responses from 20,771 full-time faculty members who teach undergraduates at 143 four-year colleges and universities. This includes tenured, tenure-track and non-tenure-track faculty members.

Discrimination Concerns

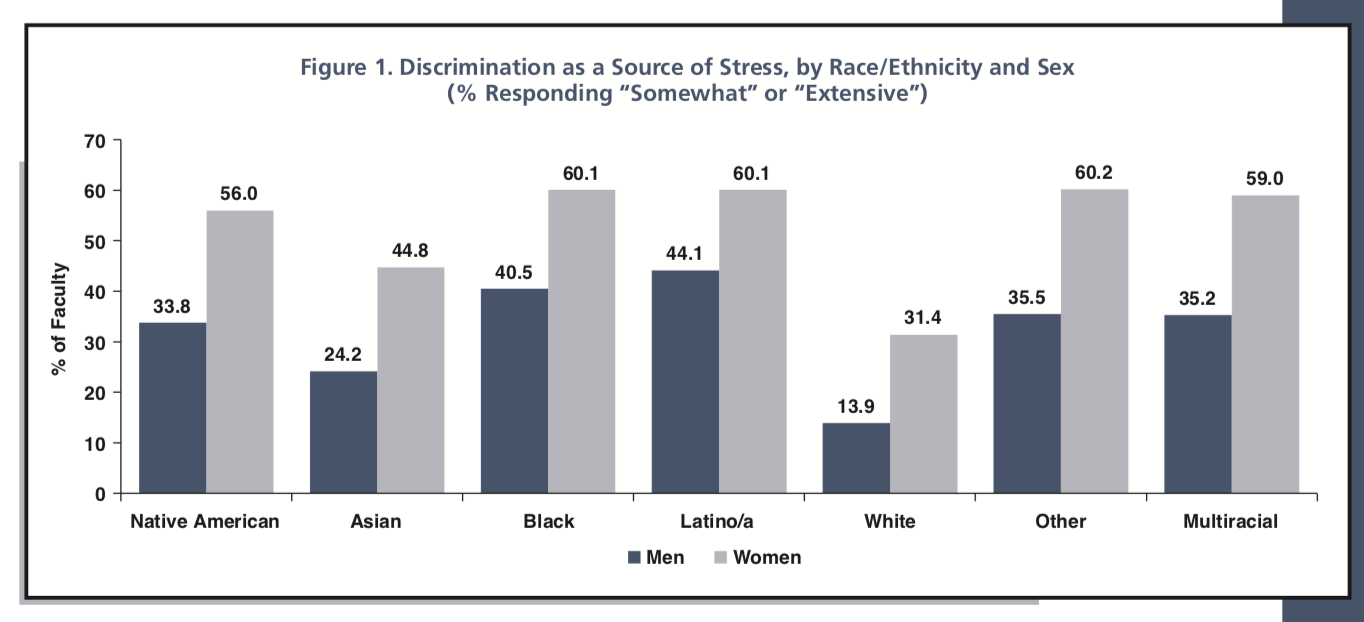

Women were more likely than men to feel that workplace discrimination is at least somewhat a source of stress (36 percent versus 18 percent), with the largest gender gaps seen at public universities. At those institutions, 19 percent of men and 43 percent of women said they’re stressed about bias.

Also unsurprisingly, white faculty members were less likely to report this kind of stress -- some 22 percent of these respondents versus about half of black and Latino professors and 31 percent of Asians. Non-Asian and nonwhite men reported higher rates of bias-related stress than do white women. More than half of female professors of color considered discrimination a somewhat or extensive source of stress.

Source: Higher Education Research Institute

By field and institution type, women in the sciences, technology, engineering and math were most stressed over discrimination.

Asked about their perception of institutional priorities, including commitments to fostering positive climates, 65 percent of professors said their institutions valued development of community. Those at private institutions were most likely to believe that their campuses valued community engagement between students and faculty members.

Regarding recruitment and treatment of women and professors of color, half of respondents said that their institutions placed a high value on promoting gender diversity in the faculty and administration. Some 56 percent of respondents said their institutions prioritized promoting racial and ethnic diversity within the faculty and administration. Whites and Asians were more likely than their colleagues of different ethnicities to say this, however. Just 35 percent of Native Americans and 43 percent of black professors said this, for example.

Over all, some 77 percent of respondents said that women were treated fairly at their institutions. Men (84 percent) were much more likely than women (69 percent) to hold that view.

While 79 percent of respondents believed that faculty members of color were treated fairly at their institutions, just 59 percent of Latino and 61 percent of black professors thought so.

What about the playing field for scholarship? “The peer-review culture and pressure to achieve excellence in the areas of teaching, research and service can foster feelings of uncertainty and doubt among some faculty regarding the adequacy of their productivity,” reads the report. Those “who feel such uneasiness may feel as though they need to work even harder to keep up with their seemingly highly productive colleagues.”

And these feelings “are often exacerbated among faculty from historically marginalized or vulnerable groups, including faculty of color, women and those without the protections of tenure,” according to the institute.

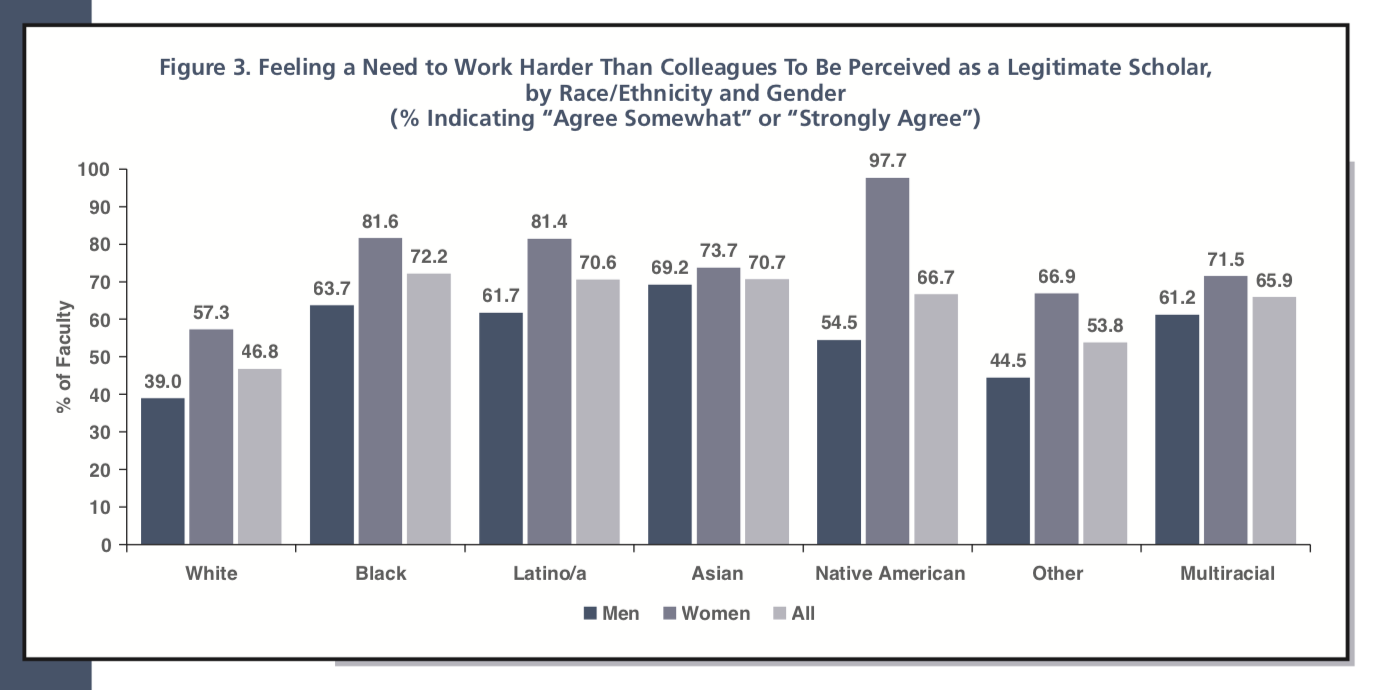

While some 51 percent of respondents said they needed to work harder than their colleagues to be perceived as a “legitimate” scholar, this varied considerably by demographic.

Among women, 61 percent believed they needed to work harder than their colleagues, compared to 44 percent of men. By ethnicity, some 72 percent of black, 71 percent of Asian and Latino, and 67 percent of Native American professors said they needed to work harder than their peers to gain this legitimacy. Just 47 percent of white professors said this.

“Almost without exception, rates of agreement among faculty of color, regardless of race, exceed the proportion of white male and female faculty who felt they needed to work harder than their colleagues to gain legitimacy,” the study says, addressing the importance of intersectional analysis.

Job security also played a role here, as did lack of clarity regarding the tenure and promotion process. Faculty members who experienced uncertainty at work were much more likely than the overall sample to think they need to work harder than their colleagues to be perceived as a legitimate scholar: three out of four faculty members reporting “extensive” stress associated with job security also indicated having a sense they needed to work harder than their colleagues. Compared to peers who reported having a clear understanding of the criteria used in promotion and tenure decisions, faculty members who lacked clarity there were 1.5 times as likely to feel compelled to work harder than their colleagues.

“The discrepancies suggest that clearly communicated signals from the campus concerning expectations about faculty productivity could go a long way in alleviating anxiety and helping faculty better calibrate self-assessments of their contributions to the department, discipline and institution,” reads the report.

This matters, in part, because believing it is necessary to work harder than peers can also contribute to higher stress levels, according to the institute. Professors who agreed either “somewhat” or “strongly” that they needed to work harder than their colleagues to be perceived as a legitimate scholar also reported experiencing “extensive” stress at higher rates than their colleagues who did not feel this pressure.

Over all, about one-quarter of respondents reported “extensive” stress due to increased responsibilities at work. One-third of professors who believed they needed to work harder than their colleagues reported having fewer than five hours on average each week of “personal time,” compared to 23 percent of respondents who didn’t.

“Although colleges and universities have made progress toward greater gender and racial diversity among their faculty, these findings make clear that the academy has significant work to do regarding equity and inclusion,” Kevin Eagan, director of the institute and assistant professor in the university's Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, said in a statement. “Any progress institutions have made with respect to enhancing the diversity of their faculty through hiring will be short-lived if women and faculty of color endure discriminatory departmental and institutional climates that serve as a major source of stress and potentially erode their ability to achieve work-life balance.”

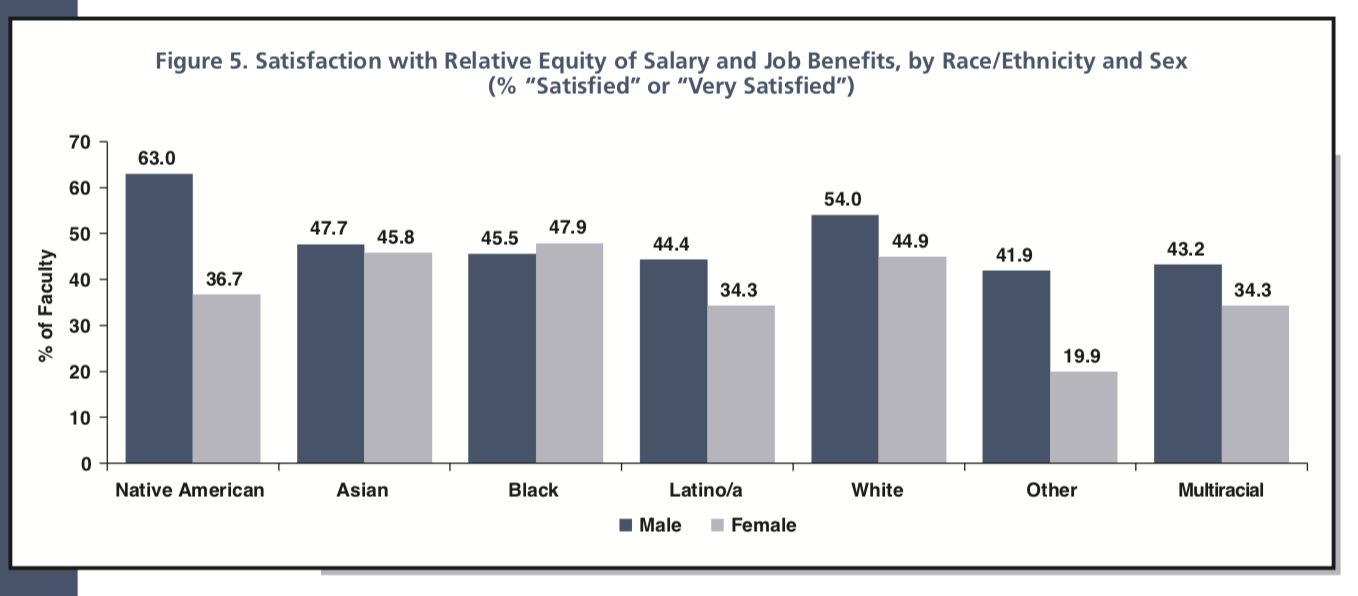

As for pay, just 48 percent of faculty members in the survey were satisfied or very satisfied with the relative equity of their salary and job benefits. One-quarter were not satisfied. Professors at private institutions were most likely to be satisfied (60 percent). And faculty members whose principal activity is teaching were less likely to be satisfied than those whose principal activity is service to clients or patients, administration or research.

Satisfaction with relative equity of pay varied by demographics, as well. Some 44 percent of female professors were satisfied, compared to 52 percent of men. Multiracial (39 percent), Latino (40 percent), black and Asian (both 47 percent) professors were all less satisfied than their white peers (50 percent).

Looking at satisfaction by STEM affiliation, STEM faculty were more satisfied (53 percent) than their non-STEM peers (47 percent).

The survey includes questions about hours spent per week on different activities. Linking this to relative satisfaction with pay and benefits, researchers found that the level of satisfaction increased as the mean hours per week spent on teaching and preparing for teaching decreased. By contrast, as time spent on scholarly writing increased, so did the level of satisfaction with equity of pay and benefits.

Teaching, Mentoring and Conflicts in the Classroom

If discrimination and bias are major points of concern for many faculty members, most professors say they’re not prepared to deal with these kinds of conflicts in their classrooms.

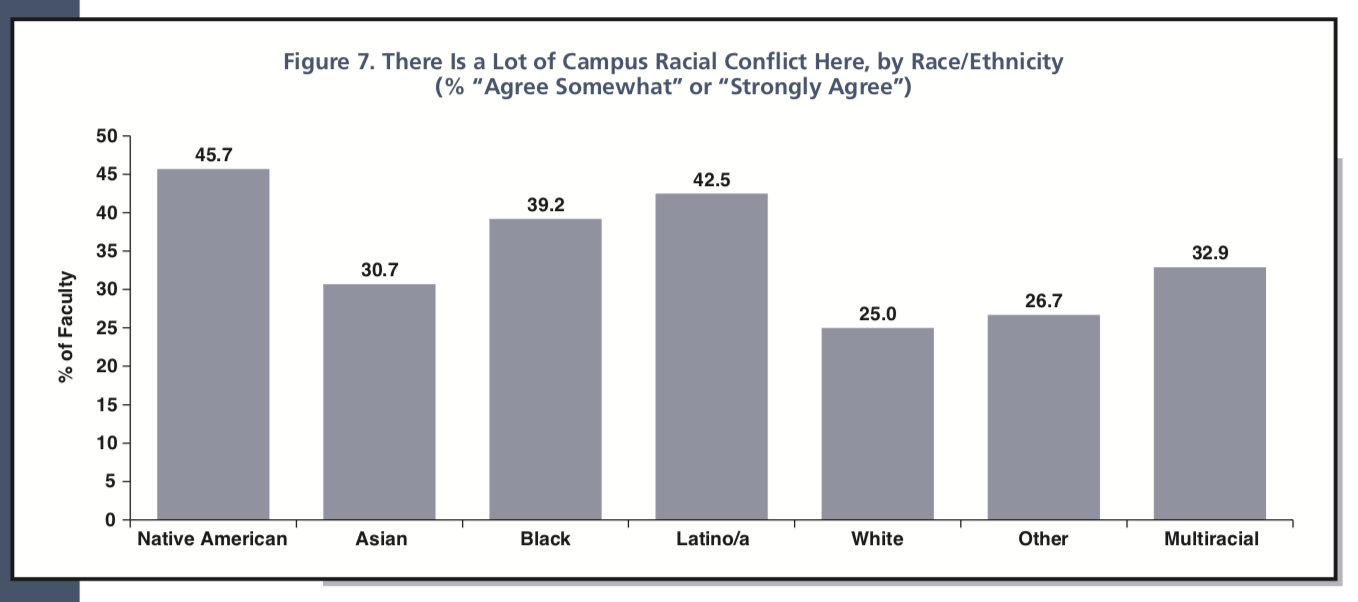

In general, 27 percent of professors felt there was racial conflict at their institution, with women being more likely than men to agree. Some 43 percent of Latino and 39 percent of black professors agreed there was a lot of racial conflict on their campuses, however.

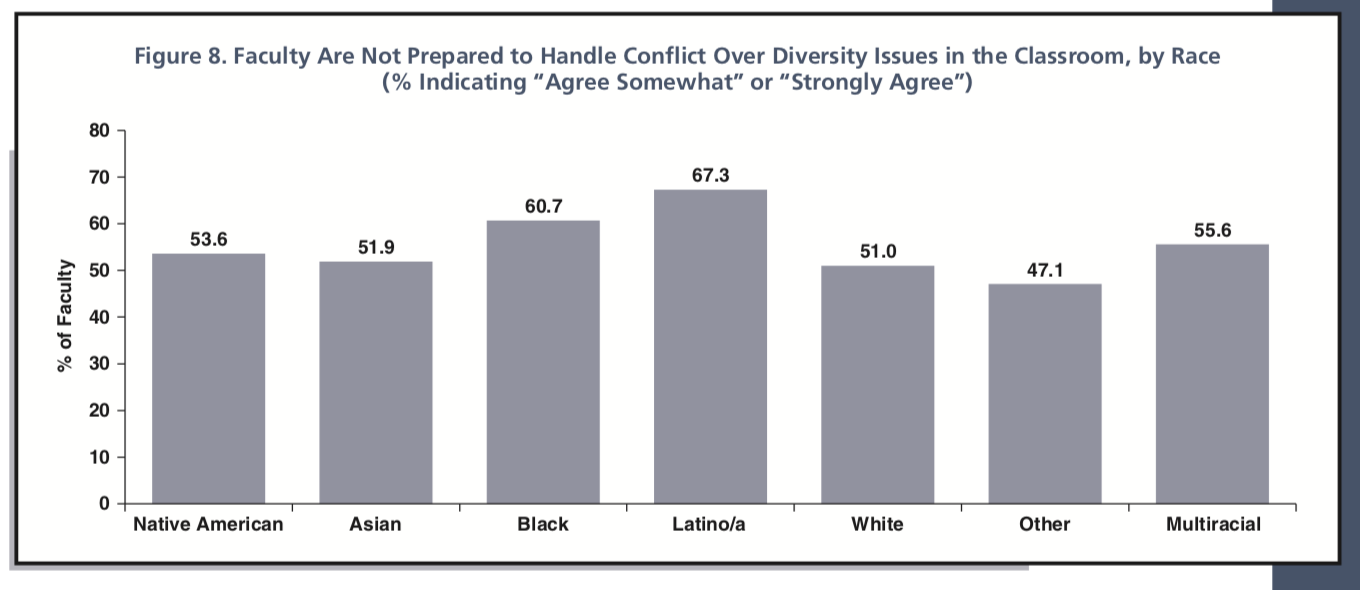

While 84 percent of professors said it was their role to enhance students’ knowledge of and appreciation for other racial and ethnic groups, less than half of professors felt they were prepared to deal with conflict over diversity issues in the classroom. More than two-thirds of Latino and 61 percent of black professors said that faculty members are unprepared for this kind of work.

Even so, 22 percent of professors reported using resources to integrate culturally competent practices in their teaching. Faculty members in engineering, math and agriculture were the least likely to consult these resources.

A survey module on mentoring was completed by 7,255 full-time professors at 56 institutions. In general, slightly more women and non-STEM professors scored higher on self-efficacy in mentoring, a composite measure of skills. Skills include providing mentees with constructive feedback, taking into account the biases and prejudices they bring to the mentor-mentee relationship, working effectively with mentees whose personal backgrounds differ from their own, and being an advocate for their mentees.

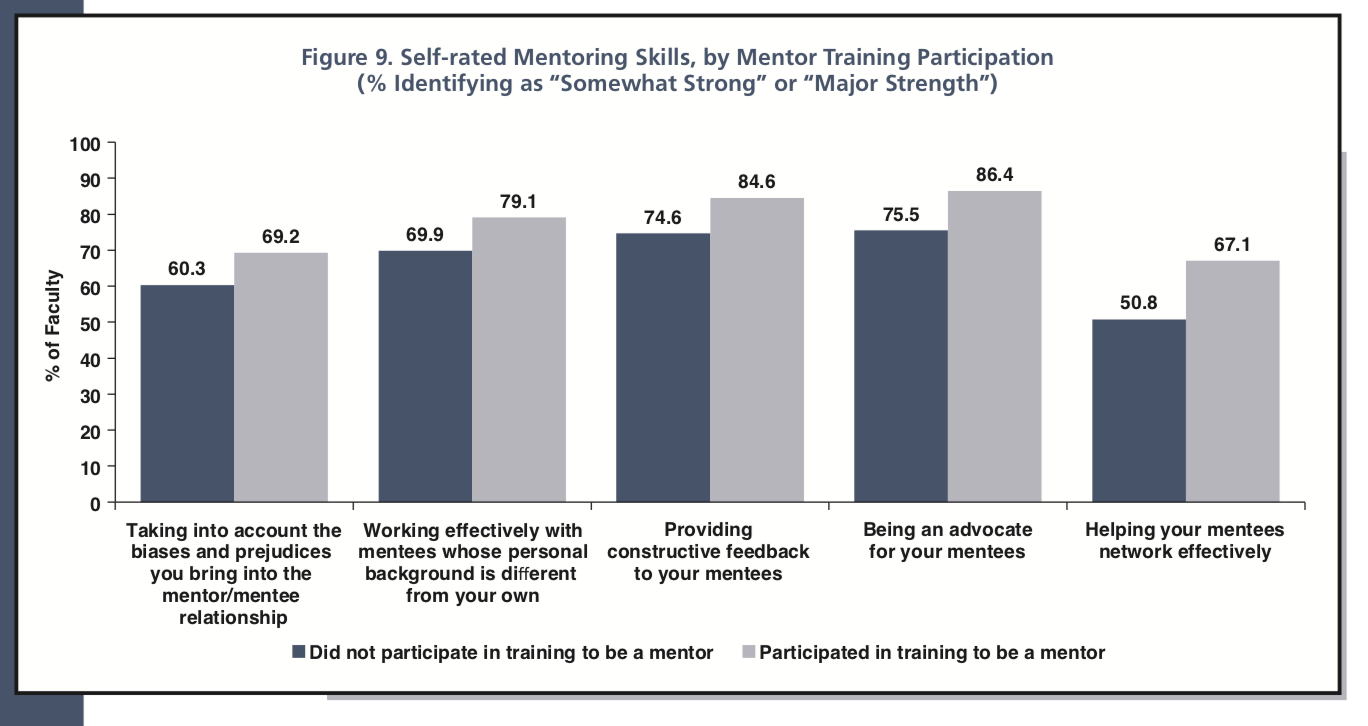

More than half of respondents said they’d participated in some type of training to be mentor, with STEM faculty (64 percent) being more likely to be trained than peers in other fields (55 percent). And training appeared to be effective, in that skills scores for those with training were significantly higher than for those without it.

Of the faculty who were currently mentoring undergraduate students, about one-fifth each mentor one or two students, three or four students, five to eight students, nine to 15 students, or 16 or more students. Professors in non-STEM fields reported mentoring more undergraduates, with 44 percent mentoring nine or more students, compared to 40 percent of STEM instructors.

Male and female faculty members reported mentoring about the same number of students. But women were more likely to rate the overall quality of their mentoring relationship with undergraduates as excellent (55 percent) compared to 50 percent of their male peers. At the same time, men were more likely to report that they engaged with their mentees weekly than were women. Beyond communication frequency, women were more likely than men to work on educational choices and strategies, explore career options, serve as role models, and convey empathy to their mentees.

Among graduate mentors, professors in non-STEM fields reported having more graduate student mentees than STEM professors did. Female faculty members in both STEM and non-STEM fields were slightly more likely to have more students than their male peers.

Some 33 percent of STEM women had at least five graduate student mentees, compared to 30 percent of STEM men. Some 44 percent of non-STEM women had at least five graduate mentees, compared to 38 percent of men.

In non-STEM fields, about 11 percent of men and 9 percent of women communicated with their graduate mentees daily. In STEM fields, about 20 of female professors and one-third of men communicated daily with their graduate mentees.

Male professors in STEM fields (67 percent) worked with their graduate mentees on their research projects and interests at higher rates than do female professors in STEM fields (50 percent).

Of the professors who completed the mentoring module, about one-third reported currently mentoring other faculty members. Some 46 percent reported having one faculty mentee, while 30 percent had two faculty mentees, 18 percent had three or four, and 6 percent had five or more.

Female professors were more likely than male faculty to have more than one faculty mentee (56 percent compared to 52 percent, respectively).

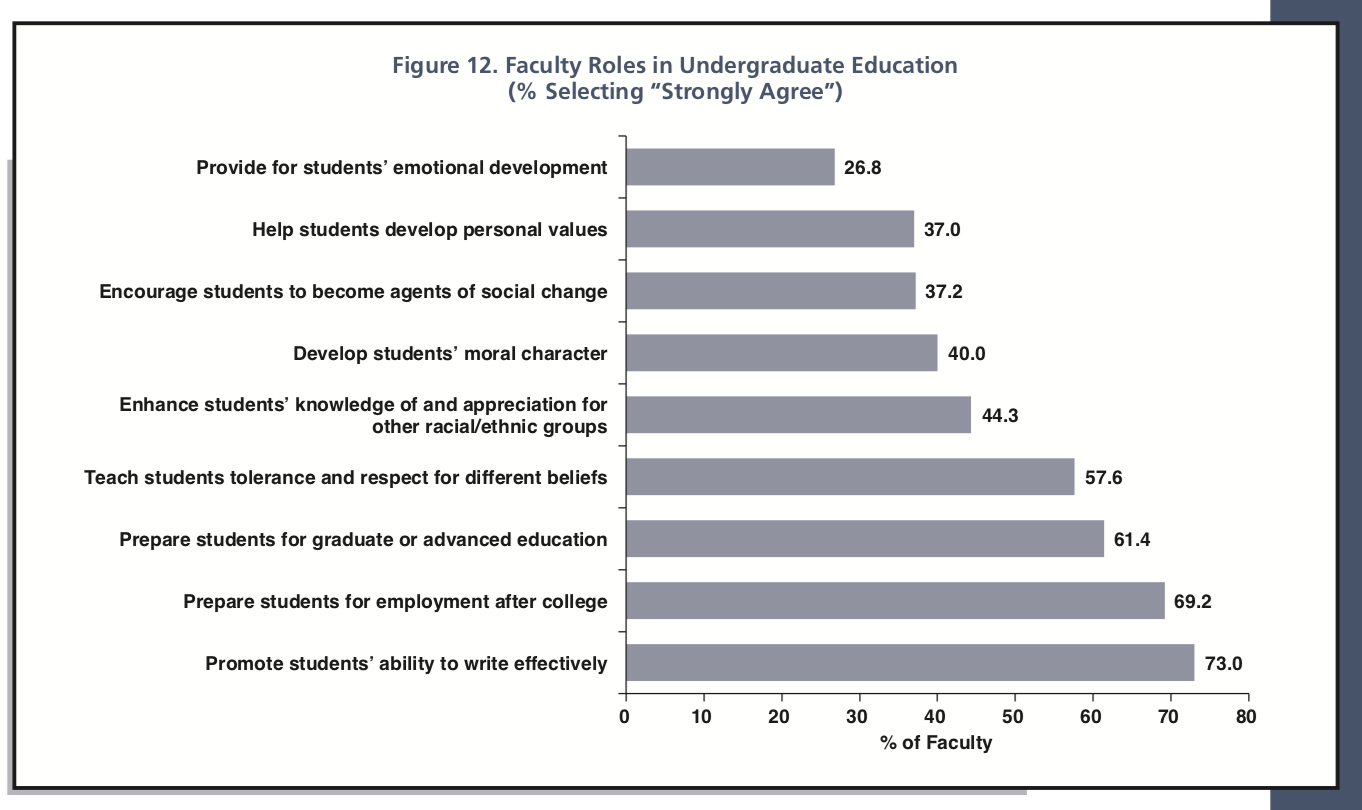

This year’s general survey asked some more specific questions than years past about faculty members’ ideas about their role in undergraduate learning. Some 73 percent of faculty strongly agreed that it is their responsibility to promote students’ ability to write effectively, but only about a quarter (27 percent) strongly believed they should provide for students’ emotional development.

Faculty members were also more likely to strongly agree that they should prepare students for employment after college (70 percent) and for graduate or advanced education (61 percent) than to encourage students to become agents of social change (37 percent) or develop students’ personal values (also 37 percent) and moral character (40 percent).

On diversity, 58 percent of faculty members strongly agree that it is their role to teach students tolerance and respect for different beliefs. Some 44 percent strongly agree that they should enhance students’ knowledge of and appreciation for other racial or ethnic groups.

Assistant professors tended to agree more with these diversity- and character-related goals than their tenured colleagues. Non-STEM faculty members were more likely to agree than their STEM peers that that they play a role in all these goals, except for preparing students for employment and advanced education.

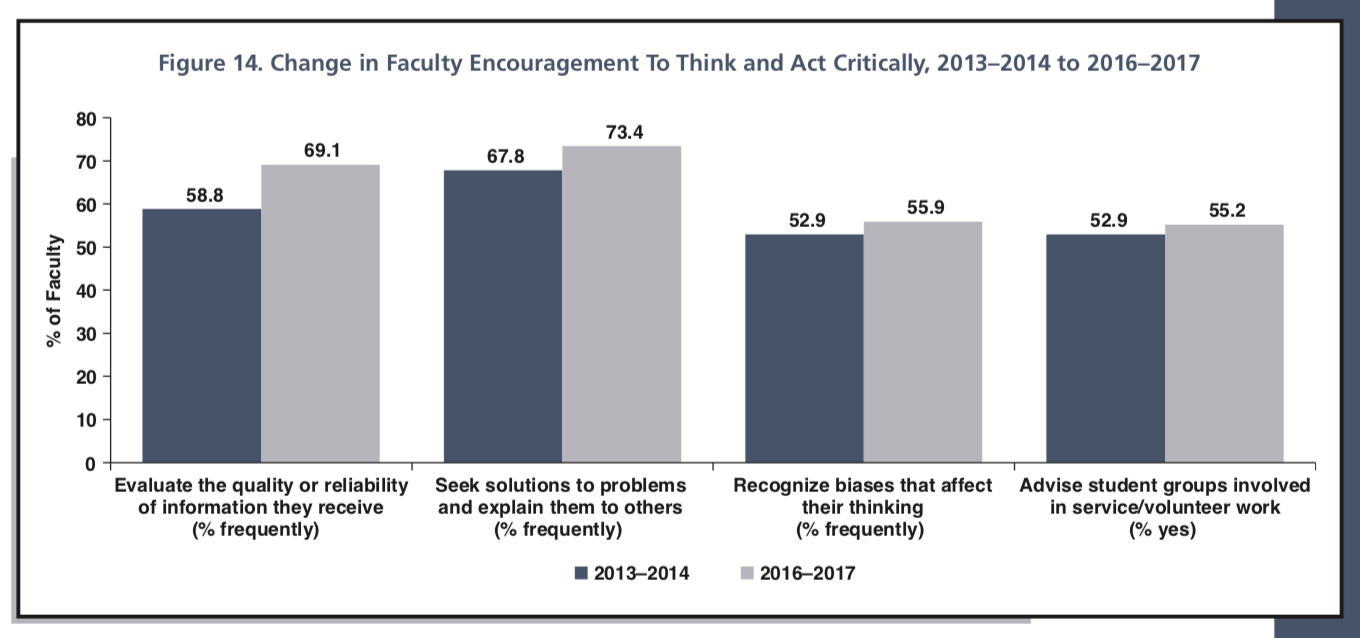

Interestingly, and perhaps significant in an era of “fake news,” larger proportions of faculty reported increases in frequency on three items relating to habits of mind than in past iterations of the institute’s survey.

Seventy percent of faculty over all reported frequently encouraging students to evaluate the quality or reliability of information that they receive. Three years earlier, this was 59 percent.

About 73 percent of professors now frequently encourage students to seek solutions to problems and explain them to others, up five percentage points from the previous survey. And 56 percent of professors reported frequently encouraging students to recognize biases that affect their thinking, an increase of three percentage points from 2013-14.

What about underprepared students? Seventy-one percent of faculty members over all agreed somewhat or strongly that their institution takes responsibility for educating underprepared students. But faculty members at private universities and nonsectarian four-year colleges were slightly less likely to agree with this idea. Faculty members at public four-year colleges and Roman Catholic and other religious institutions were the most likely to agree.

Faculty members who were teaching remedial or developmental courses at survey time were more likely to agree that their institution takes responsibility for educating underprepared students. About 5 percent of professors over all were teaching remedial work, and they were more likely to say that students in theses classes lacked the basic skills for college-level work. Lecturers or instructors, not tenure-track respondents, were mostly likely to teach these classes. Math and other “technical” professors were more likely than their peers in other fields to be teaching these courses.

Outside the Classroom

On professional development, 69 percent of respondents said that there was adequate professional development for them. And, surprisingly, instructors were most likely to say this -- not their tenure-line peers. But just about half of professors participated in professional development within the previous year. Of those, 50 percent participated in teaching development. And one-quarter of those said they received incentives to develop new courses. Others received incentives for integrating technology into the classroom.

Other faculty members participated in professional development for research funding, including research skills development, grant-writing activities and writing internal grants.

Regarding their political views, less than 1 percent of faculty members identified as far right, 12 percent as conservative, 28 percent as “middle of the road” and 12 percent as far left. The biggest share -- 48 percent -- identified as liberal. That’s just about the share (49 percent) of faculty members who said this in 2013-14. And it’s actually less than the peak share -- 50 percent -- of faculty members who said they were liberal, in the 2010-11 administration of the survey.

Kiernan Mathews, executive director of the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education, said the institute’s triennial monograph is always a “welcome arrival,” since its one of the few large-scale data sets about faculty available to researchers. The collaborative surveys faculty members, too, but the National Survey of Postsecondary Faculty hasn’t been funded by Congress since 2004, he noted.

To that point, Mathews said that survey research projects like the institute’s collect “so much data, it becomes an important editorial choice to decide what to highlight.” The choices this time have several effects, he added. Some bring “long-hidden issues into the sunlight, like the potential effects of training mentors, and some raise critical questions about faculty blind spots, like the low proportions of white faculty who are aware of racial conflict on campus.”

"I hope that white faculty, in particular, take a hard look at these results and ask why their perceptions and experiences as faculty differ so much from those of their racially minoritized peers," Mathews said.