You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Student evaluations of teaching -- which have been shown again and again to be subject to student biases, especially gender bias -- remain as controversial as ever. And two new studies of these evaluations, or SETs, are more fuel for the fire.

The first paper suggests that relatively simple changes to the language used in SETs can make a positive impact in assessments of female professors. Yet the authors warn that if these changes were widely adopted, students (and their biases) might adjust to the new system -- and the positive effect for female professors might wear off.

A second study finds that professors are seen by students as better teachers before they earn tenure. The authors say that this is not a reason to do away tenure entirely, just that increased job security inside or outside academe may come with decreased "quality of output."

Mitigating Gender Bias

The bias paper, published in PLOS ONE, cites experimental research showing that gender bias accounts for up to a 0.5-point negative effect for women on a five-point scale. And yet, it says, “there are few effective evidence-based tools for mitigating these biases.”

What if students were made aware of their potential biases, the authors wondered? While long-term reductions in student biases are beyond a simple intervention, they wrote, it may be possible to limit the immediate problem of biases in SET by “cuing students to be aware of their biases, providing motivation to not rely on them, and suggesting alternatives to their stereotypes.”

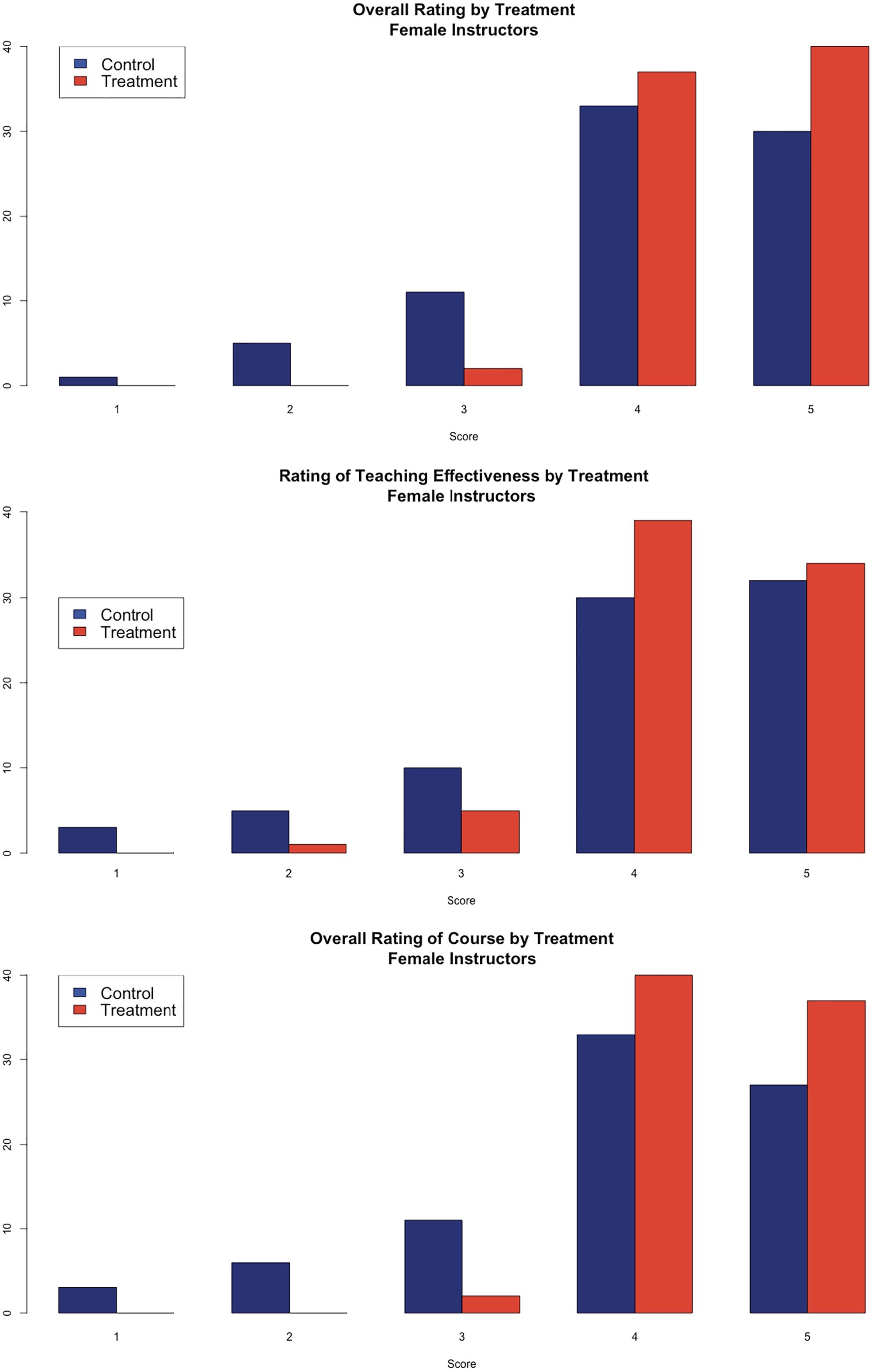

To test their idea, the authors conducted an experiment in pairs of large introductory courses in biology and American politics at Iowa State University last spring. All four sections were taught by white professors, allowing the researchers to eliminate effects from confounding racial biases. One section in each field was taught by a man and the other by a woman.

SETs at Iowa State are conducted online, from a link in students’ email. For each course in the study, students received one of two evaluation formats: the standard department format or the “treatment” evaluation. Students were randomized within courses, not across courses, to receive different evaluation formats so that professors could be compared to themselves, not other professors who may actually be better teachers.

Unlike the standard evaluation, the treatment evaluation included the following language, which the researchers expected would mitigate gender biases:

Student evaluations of teaching play an important role in the review of faculty. Your opinions influence the review of instructors that takes place every year. Iowa State University recognizes that student evaluations of teaching are often influenced by students’ unconscious and unintentional biases about the race and gender of the instructor. Women and instructors of color are systematically rated lower in their teaching evaluations than white men, even when there are no actual differences in the instruction or in what students have learned.

As you fill out the course evaluation please keep this in mind and make an effort to resist stereotypes about professors. Focus on your opinions about the content of the course (the assignments, the textbook, the in-class material) and not unrelated matters (the instructor’s appearance).

Among other questions, every student involved in the study was asked the following about their instructor, on a five-point scale:

- Your overall rating of this instructor is?

- What is your overall rating of the instructor’s teaching effectiveness?

- And your overall rating of this course is?

Students were also asked about their gender, as is standard for Iowa State evaluations, allowing the researchers to examine that, as well. The authors guessed, based on existing literature, that male students would be more biased against female instructors than female students would be. The authors controlled for students' expected grades in a course.

What happened? The language seemed to have a small but significant, positive effect for female faculty members on all three questions -- and no effect for men. The answers to the overall evaluation of teaching were 0.41 points higher in the treatment condition. The difference in the means for the teaching effectiveness question were 0.30 points. For the overall evaluation of the course, the treatment condition was 0.51 points higher than the control.

Regarding the student gender hypothesis, the researchers found that the intervention had no effect on women’s evaluations of female professors. There was some evidence of an effect for male students rating female professors on overall rating of the course and the instructor, but not teaching effectiveness. A more advanced analysis reduced this effect, however.

Across courses, the effects of the evaluation language were “substantial in magnitude; as much as half a point on a five-point scale,” the paper says. “This effect is comparable with the effect size due to gender bias found in the literature. There is no evidence of a similar effect on the evaluation of male instructors. Given the outsized role SET play in the evaluation, hiring and promotion of faculty, the possibility of mitigating this amount of possible bias in evaluations is striking.”

Source: Peterson, PLOS ONE

A note of caution, however. “The implication of these results is that universities should adopt some form of this language to mitigate the gender biases in SET,” the study says, yet “we are somewhat uncertain about the broad applicability of these results.” Why? The effects observed “may be magnified by the unusual nature of the situation for the students,” meaning it’s possible that if an institution saw “widespread adoption of bias language students would be less likely to notice the language and its effects would lessen.”

Further research is needed, therefore, “to determine the most effective way to mitigate gender bias in SET on a large scale.”

Teaching and Tenure

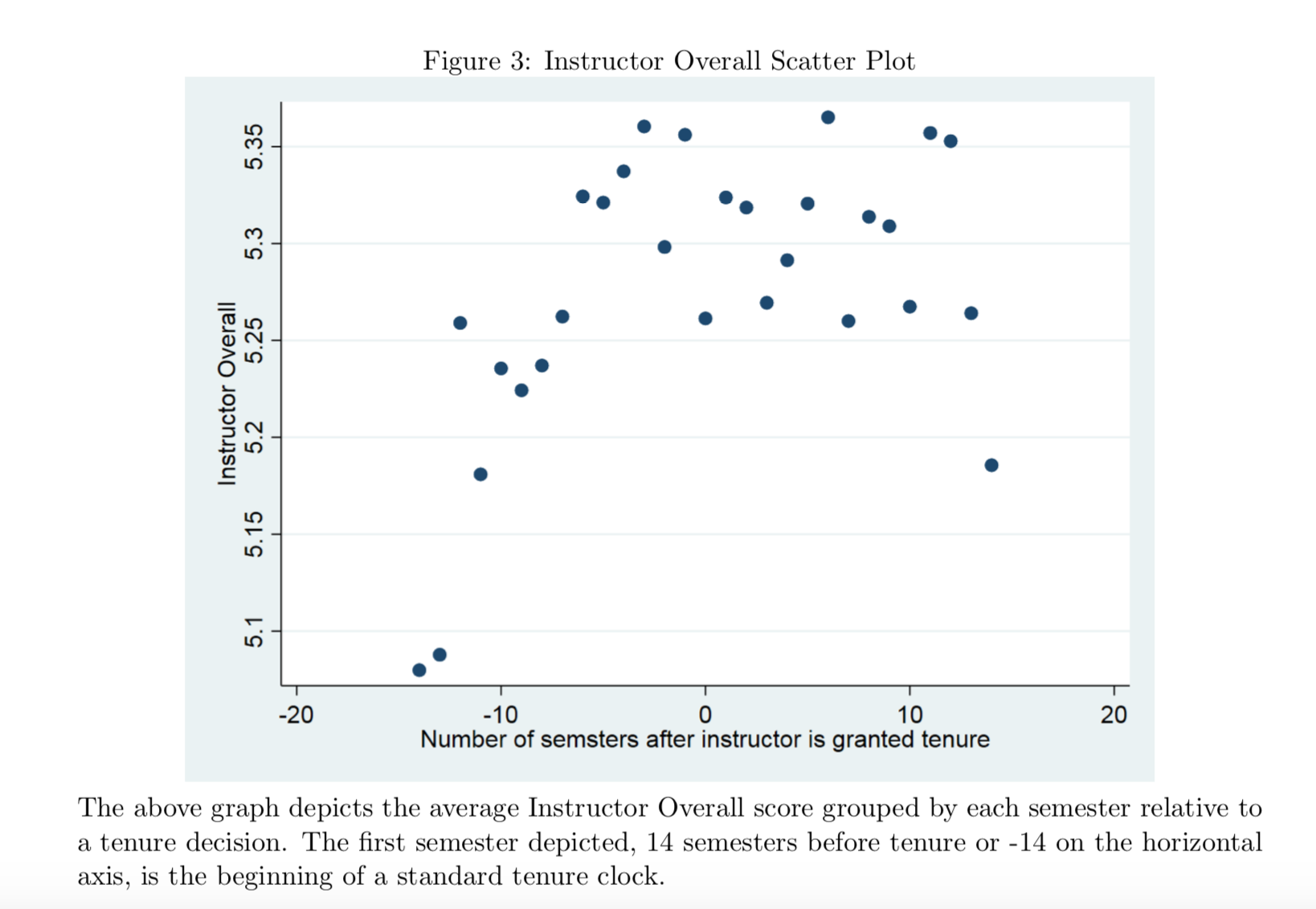

And what about tenure’s effect on teaching -- at least students’ perceptions of it? The working paper on that topic involves 250 professors granted tenure over 11 years at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Together, the professors taught more than 6,000 courses to undergraduates and graduate students, and their many SETs of course included proxies for teaching effectiveness -- namely overall ratings for course and instructor.

All such questions are subjective and self-reported by students, the paper notes. But the authors say they looked “within instructors,” pre- and posttenure, “not across instructors,” for consistency.

Results of the instructors’ pre- and posttenure ratings show what the authors call “a small but persistent decrease” in the instructor over all and course over all score, equivalent to up to a sixth of a standard deviation.

Source: Gourley

While the results seems to show an “in-class behavioral change” in instructors after tenure, the paper says, there exist alternative explanations.

The authors were most concerned with the possibility that professors teach different courses after tenure. Yet the study’s most restrictive specification or step compared the same instructor pretenure and posttenure in the “exact same course, leaving few possible alternative explanations to a tenure mechanism.” The results are there are “qualitatively similar to the main set of results: instructors receive worse evaluations after tenure than they did prior.”

The researchers also found a statistically significant decrease in an instructor’s student-reported availability, instructor effectiveness and how much the student reported to have learned posttenure.

What Now?

David A. M. Peterson, professor of political science at Iowa State and lead author on the gender bias paper, said the biggest takeaway for higher ed is that a small, relatively easy-to-adopt intervention can produce “sizable changes” in evaluations of female faculty members.

At the same time, he said, “The concern we have is that the effects will be much smaller if the change is universally adopted.” More generally, “universities absolutely should not make this type of change and then assume that they have fixed the problem,” Peterson added.

Like many critics of student evaluations of teaching, Peterson also said SETs probably shouldn’t be used in high-stakes personnel decisions. They can be useful for “individual faculty members to get an assessment of their courses,” but are “quite problematic for comparing faculty to one another or to some abstract standard.”

Asked about possible other factors behind his findings, Patrick Gourley, assistant professor of economics at the University of New Haven and co-author of the posttenure paper, reiterated that the strength of his research design is that it’s not comparing scores across professors.

“We even take into account the possibility that professors may teach different courses after gaining tenure. Still, the negative impact exists,” he said, adding, “Why else would professors suddenly change their teaching six to eight years after starting a faculty position?”

Gourley said that it’s possible that professors have a first child or more children as soon as they get tenure and “have less time to devote to teaching.” But even that would be an indirect effect of tenure.

Tenure critics will certainly seize on this research as evidence that tenured professors are “deadwood” -- even if other research on other dimensions of faculty work contradict that.

Asked about how his findings should be interpreted, Gourley said he’s currently working toward tenure himself and that the tenure debate is “complex with many good arguments on both sides.” So his own findings should “should first be kept in context,” in that the “magnitude of our effect is small,” he said.

Gourley also noted that the finding is based on “observation of student-perceived teacher quality,” and not an “objective measure of how much a student is learning.” And while it seems likely that professors work harder on teaching while on the tenure track, given the “large benefit” of getting tenure, he said, “the effect we find represents a reversion to what would have happened had no tenure system existed in the first place.”

In other words, he explained, “perhaps the tenure system makes teachers better at the beginning of their career than they would have been otherwise.” Gourley also noted that service requirements typically increase significantly posttenure, partially counterbalancing the negative effect on teaching.

“Those caveats aside, this does need to be included as a possible cost of the tenure system, and should be viewed as one of many in the list of costs and benefits.”

Gourley found no evidence of gender bias in his study. But he said it wasn’t surprising with respect to this particular paper, in that it would imply that students “view the tenure-induced teaching change in professors to be larger in one gender than in the other.”

To the contrary, he said, most students aren’t aware of who’s tenured and who isn’t.