You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

The term “invisible labor” has been used to describe the unrecognized work underrepresented faculty members are called on to do by virtue of that status: mentoring students who see aspects of themselves in their professors, for example, or otherwise engaging in inclusion and diversity work.

A new study in Nature: Ecology and Evolution seeks to make that labor more visible, at least within the fields of ecology and evolutionary biology. The findings have implications for how universities allocate resources for diversity and inclusion and how professors who engage in that work -- particularly those who do the heavy lifting -- are evaluated and valued.

Based on survey responses from 469 faculty members in ecology and evolutionary biology across the U.S., the researchers found that most respondents engaged in diversity and inclusion work. But those who did the most work were significantly more likely to self-identity as nonwhite, nonmale or first-generation college attendee.

“Our survey findings indicate that traditionally marginalized groups are bearing the primary responsibility for creating a more diverse and inclusive culture within ecology and evolutionary biology programs in the U.S.,” the study says. “Non-white, non-male and first-generation faculty disproportionally reported engaging in and contributing to diversity and inclusion. Our results complement other studies that find underrepresented faculty are more likely to incorporate diversity-related content into course materials and contribute more to service than their peers.”

Ninety-two percent of respondents reported engaging in diversity and inclusion activities and felt that their institutions valued those efforts. But the majority (72 percent) also felt that diversity and inclusion work didn’t really matter in tenure decisions. About half of respondents felt they valued diversity work more than their peers did.

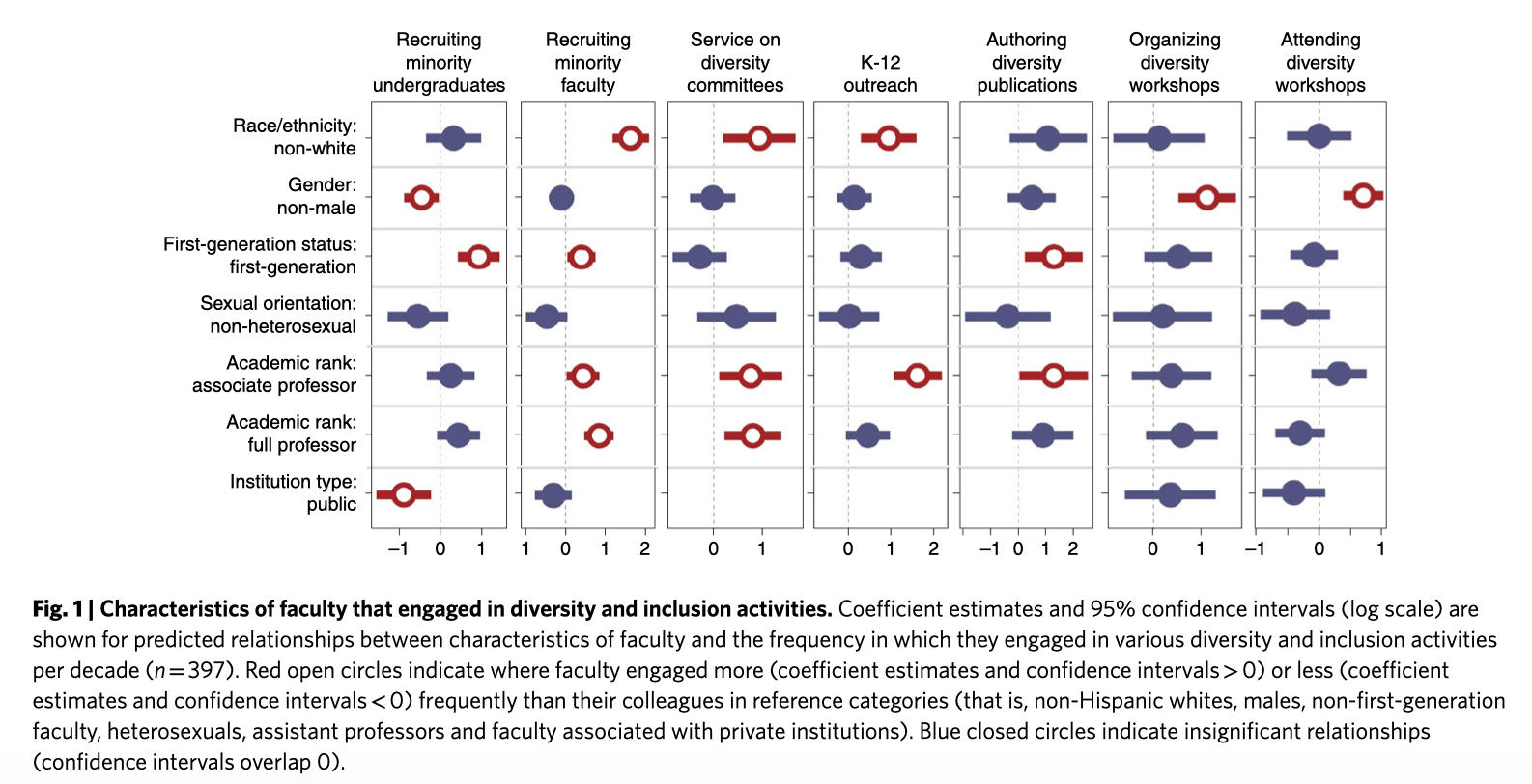

Non-white, non-male and first-generation faculty members, as well as those in associate or full professor positions, were consistently more likely to engage in diversity and inclusion activities, the study says. Non-white professors recruited minority faculty members, engaged in outreach to diverse K-12 schools and served on diversity committees more frequently than non-Hispanic white faculty members. First-generation faculty members engaged more frequently in recruitment of minority professors and undergraduate students and were more likely to publish diversity-focused, peer-reviewed work.

Non-male faculty members organized and attended diversity workshops more frequently than male professors. The single exception to the overall trend is that non-male faculty members were less likely to recruit minority undergraduate students than their male colleagues.

Source: Jimenez and Laverty

Most survey respondents were white (88 percent) and about half were male (52 percent). Twenty-two percent were first-generation college attendees. About half were full professors and the rest were assistant or associate professors.

Of respondents who actively engaged in diversity work, more than half strongly agreed that they were motivated by the desire to train diverse leaders as role models, increase scientific literacy among diverse groups, improve research and teaching in their fields and because they felt morally obligated were motivated by the perception that engagement in diversity and inclusion would enhance success with grants or tenure decisions.

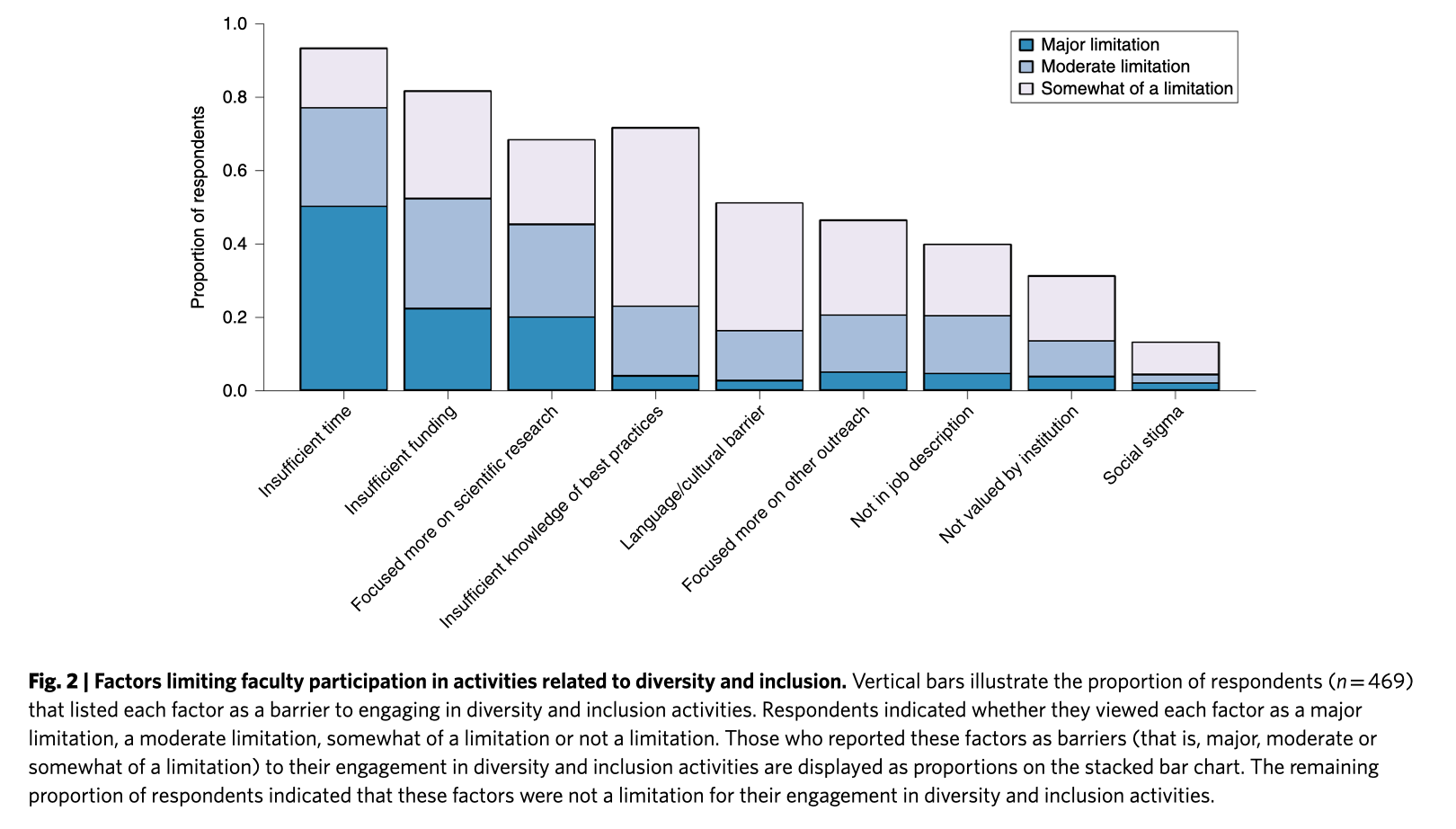

The biggest factors limiting faculty engagement were insufficient time and funding, rather than training or knowledge.

Beyond providing evidence of invisible labor, the authors offer suggestions for institutions working to make faculty work more equitable. Co-author Liba Pejchar, an associate professor in the department of fish, wildlife and conservation biology at Colorado State University, said it’s already a best practice to ask candidates for faculty positions to demonstrate commitment to diversity and inclusion in their applications -- often called diversity statements.

Yet once these faculty members are hired, she said, “we never again ask them to affirm how they have met this commitment.” Pejchar and her team recommend incorporating evidence of this “shared responsibility” into annual evaluations, “and possibly even tenure and promotion decisions makes sense if we are truly to transform our field.”

Everyone should be practicing “inclusive pedagogy and taking time to mentor students from diverse backgrounds,” for example, she said.

As for resources, Pejchar said that colleges and universities should allocate sufficient funding to recruit and retain diverse undergraduate and graduate students and train all faculty members in inclusive pedagogy and mentoring. They should also ensure that opportunities, such as conferences and workshops and summer research experiences for students, are “financially available to all, regardless of socioeconomic background.”

Lead authors Miguel Jimenez and Theresa Laverty, who both work in Pejchar’s lab, as a graduate student and postdoctoral researcher, respectively, wrote in a joint email that one of their most encouraging findings was that the “vast majority of our respondents highly valued and engaged in diversity and inclusion activities.” So they’re optimistic that the same is true across the natural sciences and beyond.

“Previous research and commentary have suspected that underrepresented faculty in STEM fields disproportionately engage in diversity and inclusion activities,” they said. “As far as we are aware, our study is the first to quantify this disparity.”

Tricia Matthew, an associate professor of English at Montclair State University who has written about invisible labor in academe, said the study “definitely holds true across the academy,” not just in ecology and evolutionary biology. She said she’s heard as much from faculty members at institutions she’s visited since she published her 2016 book, Written/Unwritten: Diversity and the Hidden Truths of Tenure.

“I note who attends the talks, who invites me and what people of color tell me about their colleagues,” she said. One observation that causes her some alarm, given the demands of the tenure track and enduring invisibility of this labor: more and more faculty members of color are taking on diversity and inclusion work during their first few years as assistant professors.

Still, Matthew understands the impulse. “They can see the problem more clearly and often their instinct is to dive in” and try to “fix it,” Matthew said. They’re “seeking a community that reflects their experiences, and they are more aware of the institutional stumbling blocks to meaningful inclusion and equity.”

Matthew pointed out that the new study’s own statistical analysis notes low numbers of responses for nonwhite participants, and the researchers’ consequent need to collapse data on race and ethnicity into either non-Hispanic white or nonwhite. (Gender data were also collapsed into male and nonmale, and sexual identity data were collapsed into heterosexual or nonheterosexual.) The authors note that their study might suffer from selection bias, meaning that people who are more interested in diversity work may have been more likely to respond to their survey. But if that's the case, they said, then the uneven work trend they observed might even be more extreme.