You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

A major 2012 study revealed significant gender bias in hiring in the natural sciences: male and female scientists alike discriminated against hypothetical undergraduate female candidates for a lab manager position whose CVs were identical to those of male candidates. The scientists rated women as less competent and even recommended paying them much less than men.

The lead author of that study piloted a similar experiment based on racial bias in the sciences thereafter. But she found that participants, many of whom were familiar with her earlier work, guessed what she was up to. She had to abandon the project to avoid compromising the data -- you can’t test people’s unconscious biases when they’re made conscious of them. More cynically, people are less prone to acting on their biases when they know someone’s watching.

Years later, another group of scientists has managed to carry out a study on racial bias in hiring in the sciences, concerning postdoctoral researchers in physics and biology. The experiment also included gender, to see how racial and gender biases intersect.

The results, published this week in Sex Roles, are startling in their magnitude. They also have major institutional policy implications, and not just for hiring.

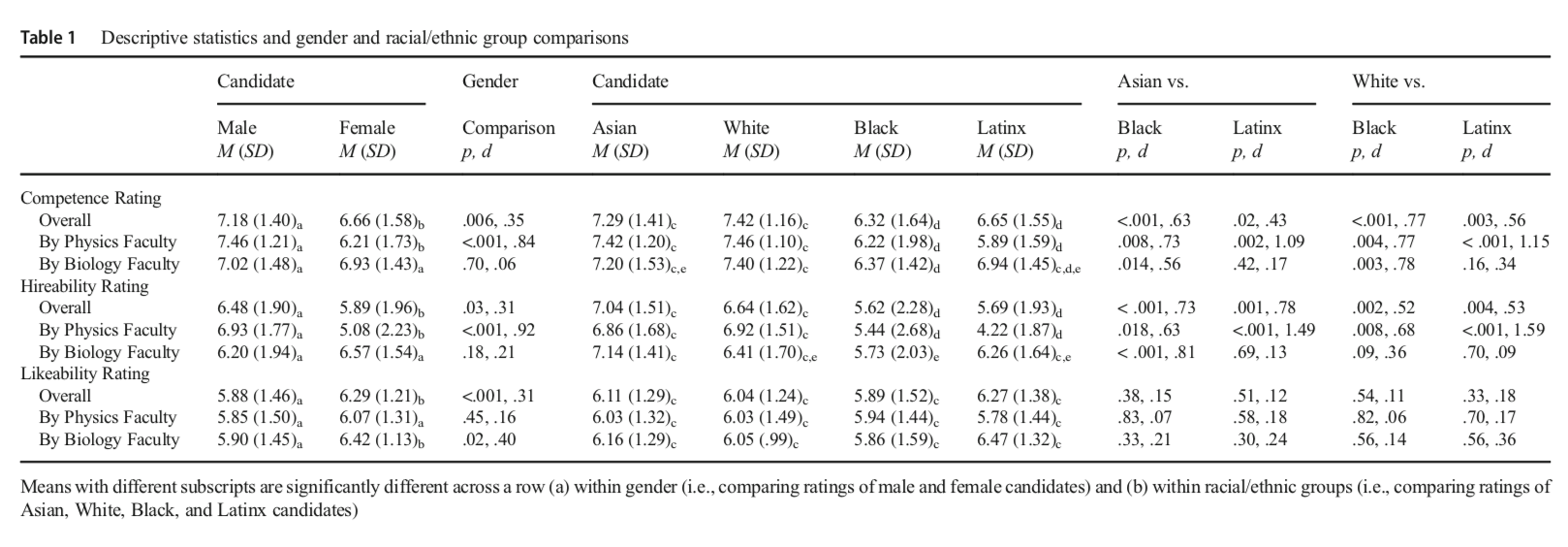

Consistent with their hypotheses, the researchers found that scientists operated on a slew of stereotypes when asked to consider hypothetical postdoc candidates with identical qualifications but different names: apparently female or male, and white, black, Asian or Latinx.

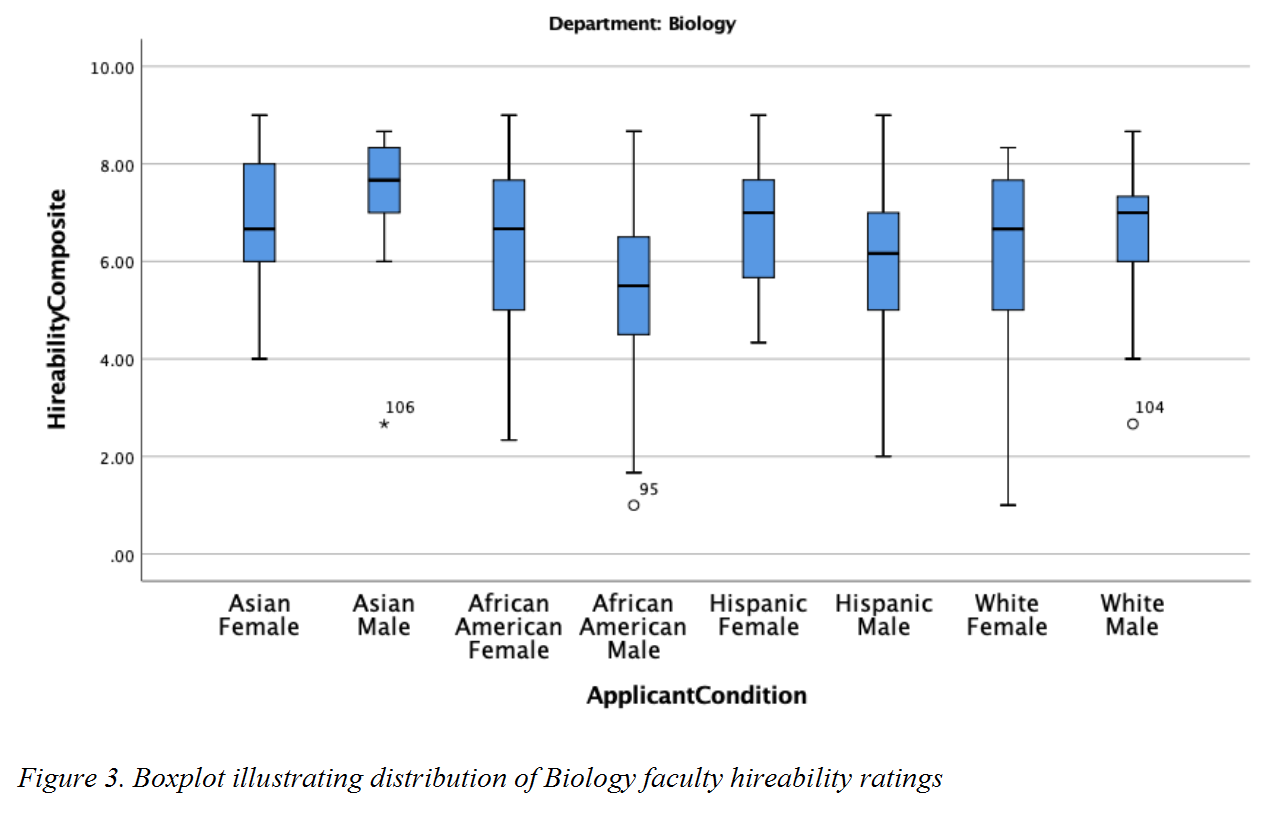

Still, there were some differences observed between biologists and physicists. Namely, biologists did not discriminate against women in terms of who they would hire or find competent on a scale of one to nine.

Source: Jessica Saunders

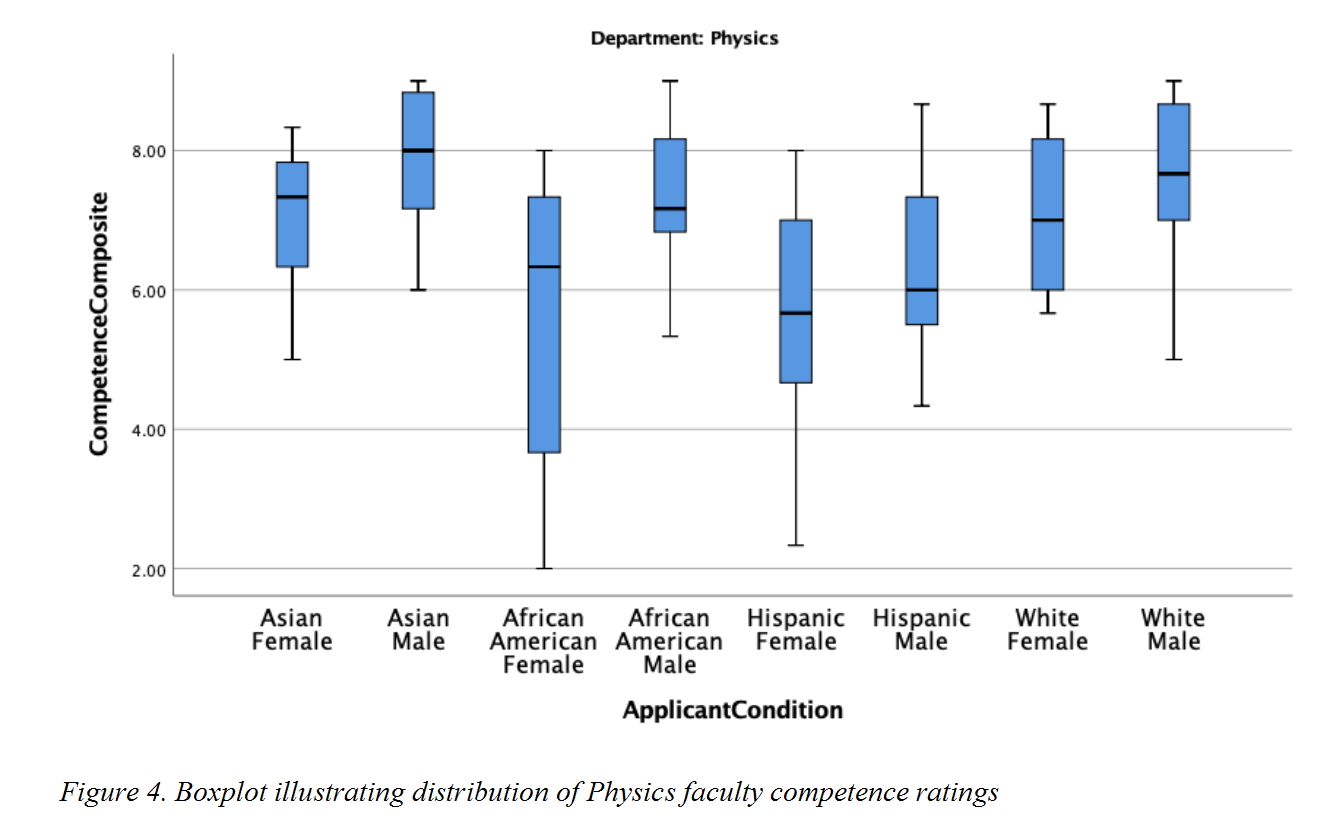

Candidates with women’s names were rated as more likable than men by both physicists and biologists. Physicists rated male candidates as more competent and worth hiring than female candidates, and Asian and white candidates as more competent and hireable than black and Latinx candidates. Black women and Latinx women and men candidates were rated significantly lower than all other candidates in physics, as well.

In biology, faculty raters saw Asian candidates as more competent and worthy of hiring than black candidates and as more hireable than Latinx candidates.

Again, the gender effect was absent in biology. Still, women of color took a double hit.

“Taken together, our findings lend experimental support to the double bind and unique challenges faced by women of color in science,” the paper says, citing research by Joan C. Williams and her daughter, Rachel Dempsey, on workplace bias against women. “Prior research has found that women of color not only experience the bias patterns encountered by white women, but also report biased experiences that differ from those of white women.”

Black women are more likely to experience isolation in the academy than white women, for example, the study says. Latinas, meanwhile, “report levels of disrespect and accent discrimination not reported by other women.”

Design and Implications

Like the 2012 study on gender alone, the new study was relatively simple in its design. Researchers asked professors of physics and biology at eight public research universities to read and evaluate the CV of a hypothetical recent Ph.D. in their respective fields who was looking for a postdoctoral position. The CVs varied only in candidates' gender and race, as indicated by their first and last names. The names and presumed identities were as follows: Bradley Miller (white man), Claire Miller (white woman), Zhang Wei [David] (Asian man), Wang Li [Lily] (Asian woman), Jamal Banks (black man), Shanice Banks (black woman), José Rodriguez (Latino man) and Maria Rodriguez (Latina woman).

Of the 635 tenured and tenure-track professors in the participant pool who were mailed surveys and study materials, some 251 faculty members responded (about a 40 percent response rate). Ninety percent of physicist respondents were male, compared to 65 percent of biologists.

Participants were told that the study was about how CV formatting and design styles influence science professors' perceptions of postdoc candidates. To maintain the cover story, the researchers included questions about that purported topic, which they later tossed. They were, of course, much more interested in the next set of questions, which asked participants to assess the hireability, competence, likability and competitiveness of a given postdoctoral candidate. More specifically, the scientists were asked survey questions about the postdoc’s overall competitiveness, the likelihood he or she would be hired at their institution, and his or her competence and likability.

Study co-author and psychologist Jessica Saunders, a postdoc research associate at the Women’s Institute of Nevada at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas, said her team’s work was inspired by the 2012 paper on gender bias in hiring in the sciences. While that paper focused on undergraduates, Saunders and her co-authors decided to frame their work around postdocs. Why? These positions are a “critical step in the academic pipeline, potentially even more important than lab manager positions,” she said. Saunders also noted that her team mailed CVs directly to faculty members, who make hiring decisions such as these on a regular basis.

Asked whether her results would hold across the sciences or beyond, Saunders hesitated and cited the difference even between biology and physics. She expressed hope that potential hiring biases across academe would be addressed by the paper's recommendations (more on that later).

Corinne Moss-Racusin, associate professor of psychology at Skidmore College and lead author of the 2012 paper on gender bias in hiring, said the new study matters because it documents that this kind of discrimination exists years later -- and because it extends the research to include race and how it intersects with gender.

The fact that the new study’s authors were able to pull off what they did, undetected, is no small feat, she added. Still, Moss-Racusin said she was sadly unsurprised by the magnitude of the effect observed.

“We’ve had anecdotal evidence of this effect for quite some time,” Moss-Racusin said, “so the fact that we have such clear demonstration of it from sound experimental research is really powerful, and it should catch the attention of the scientific community.”

Like others who have discussed and shared the research online and elsewhere, Moss-Racusin highlighted the lack of a gender bias effect in biology as compared to physics. She said that might be because there are more women in biology than in physics, but there’s no way to know for sure. Her study, involving scientists in several fields, didn’t find evidence of interfield differences.

As for what Moss-Racusin called the “million-dollar question" -- how to move the dial on gender and racial bias in hiring in science -- she said blind hiring would make a difference, in theory.

In reality, she said, at least in academe, it’s impossible to truly blind a hiring committee to a candidate’s race or gender throughout the process. Academic CVs include publications, for example -- a quick google of which reveals authors. There are ways to avoid that, too, such as quantifying research impact without naming a specific article. But then there are interviews.

“The short or final list of candidates still comes down to human beings making decisions about other human beings,” she said.

Moss-Racusin said it’s also somewhat dangerous to use shortcuts, such as blind hiring, to overcome biases, in that it may make people feel “morally credentialed.” Real progress requires more than that from both faculty members and the institution. Ideas include rethinking paid parental leave and other policies that might feed some of the biases in the first place.

“This is about shifting attitudes and shifting the systems that those attitudes exist in.”

Saunders agreed that it’s generally not possible to make CVs completely blind. So the paper suggests that hiring materials only include surnames to match the information found in citations. The paper also suggests adopting antibias trainings to target intersectional identities, such as gender and race, simultaneously. And the researchers recommend that all search decisions “be undertaken by a committee, providing additional checks and balances.”

Moss-Racusin said there’s no reason to believe that the new paper's results wouldn’t apply to faculty hiring, as well.

“Sorry,” she said.