You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Thousands of community college students transfer to Arizona State University every year, some before obtaining their associate’s degrees. While many will successfully graduate from Arizona State with a bachelor’s degree, the remainder risk joining the 37 million Americans with some college credit but no degree.

To counter this, Arizona State is working with local community colleges to share transfer students' academic records, enabling colleges to monitor when their former students have earned enough credits to be awarded an associate’s degree -- a process known as reverse transfer.

But this process is far from straightforward. Data sharing is dependent on students' permission, and communication between the university and the college can be stilted. Additionally, community colleges have to decode student records presented in different formats and decide whether the courses students take at a university are equivalent to their own.

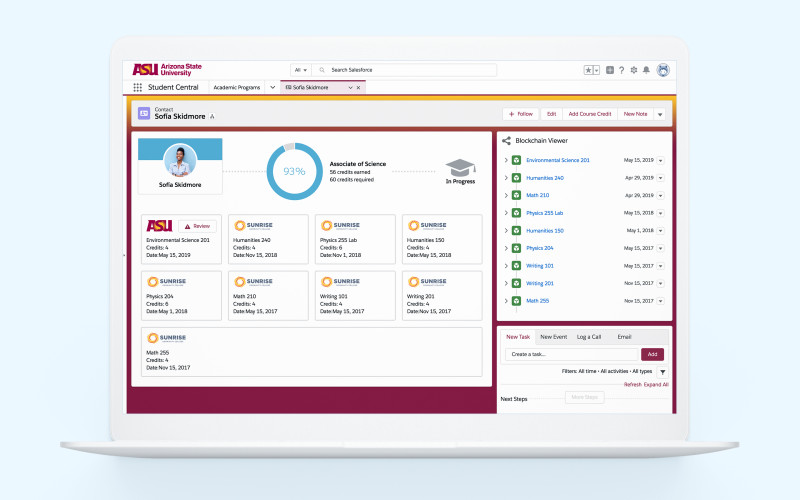

Arizona State is rethinking how this student data might be exchanged. In partnership with Salesforce, the university’s central enterprise unit, EdPlus, is creating a student data network that will enable participating institutions to share and verify students’ academic records using a distributed ledger technology such as blockchain.

Donna Kidwell, chief technology officer at EdPlus, said that reverse transfer is just one area where the institution hopes to make its network of verifiable and secure credentials useful. The technology could, for example, be used to help global institutions and employers verify the academic qualifications of refugees. “We would like to do work in that space, but it’s a really hard issue to solve,” she said. For now, transfer credit represents a more manageable arena for the university to focus its blockchain efforts.

“We have quite a lot of sophistication in our transfer credit system already -- we know what it takes to map the learning experience of one institution to another,” she said. “So we’re not starting from scratch. We already have processes in place.”

One of the aims of the project is to make student information “bi-directional” so that once students transfer to Arizona State, the community college they transfer from will continue to receive feedback on their progress, said Kidwell. Until recently, this wasn’t happening with any regularity, she said. Some colleges weren't even aware when their students enrolled at Arizona State.

“We want to optimize those pathways back and forth between us and facilitate conversations with faculty on both sides so that we can support students who are creating their own path towards a degree,” said Kidwell. It’s possible that greater insight into these “DIY” student journeys might also help the university understand where there are new program opportunities, she said.

There is a population of students at Arizona State who have amassed large amounts of college credit but have nothing to show for it, said Kidwell. “Saying you have 86 credit hours towards a degree isn’t very meaningful on a résumé,” she said.

Ted Bland, reverse transfer coordinator for the Maricopa Community College District in Arizona, said his district sends thousands of students to Arizona State each year. Part of Bland's role is to review these students' records and determine whether they have earned sufficient credit be awarded an associate's degree from their former college.

Since 2015, the Maricopa Community College District has awarded associate’s degrees to over 900 students through its reverse transfer program. Bland notes, however, that each student's record must be reviewed manually to determine whether the student has taken the right kind of courses to be awarded a specific degree. The process is time-consuming, he said.

With more students earning associate's degrees while at university, it is hoped that more students will go on to complete their bachelor's degrees, said Bland. Research suggests that students who complete their associate's degree before transferring to a university are more likely to graduate successfully, he said. The Maricopa district is currently reviewing whether awarding associate's degrees to transfer students gives a similar boost to bachelor's degree completion. While it's a little too soon to say, preliminary data suggest that students awarded degrees through reverse transfer are more likely to succeed at their university, said Bland.

Though Maricopa is not yet involved in Arizona State’s blockchain project, Bland is eager to participate. He acknowledges, however, that it may take some time to adjust to a new system. “It will never solve all our problems, but it could definitely connect more systems -- creating a more universal system and more uniform data,” he said.

“Blockchain is going to be the future of academic records,” said Bland. “The technology would certainly provide for greater fluidity. It will also allow students to own their own academic records.”

The first test for the blockchain platform is the Foothill-De Anza Community College District in California, where state funding is being tied to student success with a new performance funding formula -- providing a good incentive for colleges to want to boost their completion rates.

Joseph Moreau, vice chancellor of technology for Foothill-De Anza, said that Arizona State reached out to the district because it is known for “pushing the envelope and trying new things.” The district also has a reputation for successfully introducing new technology to other colleges, said Moreau.

Moreau hopes that the blockchain platform will give the district greater insight into why some students transfer before gaining their associate’s degrees.

“There are lots of different reasons why students might transfer. It could be a question of timing, finances, family, maybe scholarship opportunities,” said Moreau. But there is another reason students transfer from community colleges in the state -- limited course availability. “The more that we know about when and why students transfer short of completing their degree program, the better job we can do to minimize that,” he said.

Arizona State has completed the “first big chunk of work” -- providing the tool to view student data such as transfer date, grades, projected graduation, etc. Moreau is excited about the potential of the “super cool” blockchain technology, but he said the project team is still working through questions about what the actual business process will look like. “It’s easy to identify students who’ve transferred and for Arizona State to transmit the data back to us -- that’s pretty straightforward.” The bigger question is "figuring out what to do with the data" and how to scale it to other colleges, said Moreau.

Making the system scalable is something that the Arizona State team has been thinking about, said Kidwell. Arizona State is partnering with Salesforce to create the platform, but the institution didn’t want colleges that don’t use Salesforce to be excluded -- the institution wants access to the system to be equitable. Access to the platform will, therefore, not require colleges to be Salesforce customers. But small, rural colleges with limited IT staff may struggle to implement the system, said Moreau. ASU is discussing how it might support these colleges.

Creating a universal system for reverse transfer, and more broadly student data, would be monumental, said Moreau. But it would mean that colleges would have to give up some autonomy on how they collect and share data. Christopher Rice, managing partner at strategic foresight consultancy Refuturing, thinks other universities might have reservations about adopting a system that Arizona State created -- meaning that community colleges will likely have to navigate multiple reverse transfer data-sharing systems for some time to come.

Arizona State partnering with colleges that transfer large numbers of students to share data bilaterally is interesting, said Rice. But the project would become "a whole lot more interesting" with the participation of a few other large state universities. “If anyone can make it work, it’s Arizona State,” he said. “But they’ll have to do the very difficult political work to get others to buy into a shared chain. They’ll face questions about sustainability, management and ownership of the information and technology, as well as the challenge of mapping knowledge from different courses at different institutions.”

Kidwell agreed it is doubtful that all colleges and universities might adopt one universal system, but she said if the institutions are able to agree on shared technology standards, then it shouldn't create an insurmountable barrier for information sharing. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology recently announced plans to develop a global standard for digital credentials -- a discussion Kidwell said her team is eager to participate in.

While universities such as MIT have experimented with blockchain, few have tried to tackle a specific issue like reverse transfer, said Rice. “Blockchain is one of those technologies where there’s a lot of enthusiasm, but you have to be careful. It’s not a silver bullet. Here Arizona State sees a real, immediate need.”

In future, Rice foresees that it’s very unlikely students will study at just one institution -- they’ll go back and forth and have multiple employers, and having secure technology to underpin “the mechanics of lifelong learning” will become extremely important. Moreau agrees. For now the focus is reverse transfer, but the bigger picture is that institutions will no longer be the gatekeepers of credentials -- “this technology will put students’ records in the control of students,” he said. “That goes way beyond just providing a model for reverse transfer.”