You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

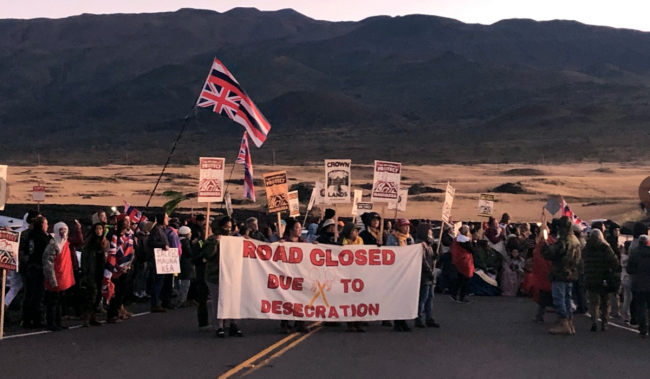

Protesters on Mauna Kea

Protests against the U.S. military’s bombing of the uninhabited but sacred Hawaiian island Kaho’olawe in the late 1970s led to a Hawaiian renaissance. And the University of Hawaii system has played a role in that movement, offering programs in Hawaiian language and Hawaiian studies and otherwise supporting Native Hawaiians and their culture.

Now Hawaiians are again occupying a sacred space as part of a larger cultural effort, at the foot of a dormant 14,000-foot volcano, Mauna Kea, on the Big Island. Protesters have been camped out there for week, halting the long-delayed construction of the $1.4 billion Thirty Meter Telescope.

But this time, the university’s path forward is less obvious, as faculty members and students are divided on the project.

“We strive to be one of the leading indigenous universities in the country, and many of the most ardent opponents of TMT have been faculty and students, so this has been extremely challenging for us,” said Dan Meisenzahl, university spokesperson. “Higher education is about the pursuit of knowledge, and this would be an amazing tool for advancement in the field of astronomy.”

That said, “again, we’re committed to be one of the leading indigenous universities in the country,” he added. “I really don’t know what’s going to happen.”

Among the planned telescope's longtime opponents is Jonathan Osorio, dean of the Hawaiʻinuiākea School of Hawaiian Knowledge at Hawaii, and a native islander who was born in Mauna Kea’s “malu,” or shadow-protection area. Osorio said this week that he and fellow protesters “do not object to telescopes. We object to them on Mauna Kea, and we have 13 of them on our mountain anyway. That is enough.”

To the Mountaintop

After a decade of legal challenges, plans for the telescope on Hawaii’s Big Island were supposed to proceed to actual construction this month. But many Native Hawaiians and their allies moved the fight against the telescope from the courts to the streets -- namely Mauna Kea's access road.

The protesters' roadblock has the project at a standstill. There have been arrests but it's unclear if anyone in Hawaii has the will to force everyone to leave. The latest official statement from the telescope came on July 10, when Hawaii governor David Ige, a Democrat, and the Thirty Meter Telescope International Observatory announced that construction would start five days later.

“After being given all the necessary clearances by the State of Hawaii and respectfully reaching out to the community, we are ready to begin work on this important and historic project,” Henry Yang, chair of the observatory’s Board of Governors, said at the time. “We have learned much over the last 10-plus years on the unique importance of Mauna Kea to all, and we remain committed to being good stewards on the mountain and inclusive of the Hawaiian community.”

He added, “Hawaii is a special place that has long pioneered and honored the art and science of astronomy and navigation. We are deeply committed to integrating science and culture on Mauna Kea and in Hawaii, and to enriching educational opportunities and the local economy.”

Only one or two places on earth -- maybe none -- rival Mauna Kea mountain’s conditions for astronomical research: the enormous volcano slopes gently, curbing turbulence from Pacific trade winds. It’s surrounded by thousands of miles of flat waters, isolated from the light interference of major cities and typically shrouded in clouds at its lower elevations. And the air at the summit is extremely dry, increasing air transparency at infrared and submillimeter wavelengths.

But the mountain isn’t revered just for its scientific value. Mauna Kea, whose summit is said to be the realm of the Hawaiian gods, is also a sacred site. Historically, only Hawaiian royalty and priests were permitted to ascend its peak or visit Lake Waiau there. Poli’ahu, Hawaii’s most beautiful goddess, is still said to live on Mauna Kea. And Hawaiians have long visited for cultural and religious reasons.

With some friction, spirituality and science -- along with tourism, which primarily benefits the once tsunami-ravaged city of Hilo -- have managed to coexist atop Mauna Kea for decades. There are already the 13 telescopes Osorio referenced, on land managed by the university. Maunakea Observatories publish more research papers annually than even the European Southern Observatory’s facilities in Chile or the Hubble Space Telescope.

Still, as part of a state plan for Mauna Kea, five of those 13 telescopes -- including one belonging to the University of Hawaii at Hilo -- have been or may be decommissioned in the near term. And there are no plans to build additional telescopes atop the mountain, save one: the TMT.

The TMT is one of a new class of giant telescopes that are unprecedented in sensitivity. The project’s board selected Mauna Kea as the site in 2009, after a five-year global search for somewhere exceptionally dry, stable and cool. And the telescope will be a feat of engineering, with a 30-meter primary mirror. When it's built, wherever it's built, it might help scientists find out what dark matter and dark energy are, and when the first galaxies formed and how. It might even provide clues as to whether there's life elsewhere in the universe.

The telescope is a joint development of the California Institute of Technology, the University of California system and the governments of Canada, China, India and Japan. But under an agreement with the telescope, the University of Hawaii will get up to 10 percent of the coveted viewing time.

Brent Tully, a professor at the university’s Institute for Astronomy in Honolulu, said Mauna Kea is simply “unrivaled as the best place north of the equator for ground-based observations.” Places in Chile are comparable, but they access the southern skies.

Mauna Kea is “the planet's gift to humanity as a place to observe the heavens,” Tully said, describing himself as a “heavy user” of the facilities already in place. The access road demonstration has shut down the existing observatories but Tully's work hasn't been affected so far.

Beyond Science and the Sacred

Of that and related protests, Tully said that Hawaiians “have a legitimate grievance with the loss of their independence as a sovereign nation,” dating back to 1893. And it’s “very sad that a joint endeavor by many peoples to expand our human awareness of our place in the universe has become embroiled in the sovereignty issue.”

While many students have spoken out against the telescope project, some have spoken up in favor. Olivia Murray, an undergraduate at Hawaii who was born and raised in Hilo, said that she’s already benefited from the economic opportunities the telescope brings to the Big Island. TMT has donated millions to the THINK Fund for academic and community engagement -- think robotics competitions and science fairs -- and, in Murray’s case, the Akamai internship program. She’s working at the Gemini Observatory in Hilo this year and last year worked at the TMT project office in California.

“Without TMT's continued financial support, many of these programs could not continue,” she said.

Tully mentioned sovereignty and Murray, economics. But Osorio, the dean, said that most of the debate has been framed as science versus the sacred. In reality, he said, there are a constellation of concerns: economic, environmental and those pertaining to racism and “consultation and consent” of Native people.

“I really object when people cynically employ the argument that it is all one sacredness to justify a project that offends so many people for so many reasons,” he said. “The biggest problem with the TMT is that more than a decade ago, a number of state institutions decided that the telescope should be built and really brooked no opposition from anyone.”

Then, Osorio said, when Hawaiians' resentment grew, proponents “seized on the notion of this shared reverence to suggest that TMT opponents are being unreasonable. But we are not.” It’s “mahaʻoi,” or an unacceptably aggressive intrusion, to require that “we accept the astronomers' reverence for science as a condition for having them honor ours,” Osorio continued. “Should we travel to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum and insist on a permanent exhibit of Native Hawaiian practices and their relationship to the study of the heavens?”

In any case, he said, “This is not about sacredness for the proponents of the TMT -- unless they really believe that somehow the rejection of this latest and very large project somehow projects a primitiveness and backwardness among our residents that embarrasses them and complicates their ability to extract more monetary value from new construction and development.”

Hawaiians’ protests have attracted the support of many across academe, who see the TMT -- in the words of geneticist Keolu Fox of UC San Diego and physicist Chandra Prescod-Weinstein of the University of New Hampshire -- as colonial science.

“Far from some replay of an ancient clash between tradition and modernity, this is a battle between the old ways of doing science, which rely on forceful extraction (whether of natural resources or data), and a new scientific method, which privileges the dignity and humanity of indigenous peoples, including Hawaiians and the black diaspora,” they wrote in The Nation. “It is a clash between colonial science -- the one which, under the guise of progress, has all too often helped justify conquest and human rights violations -- and a science that respects indigenous autonomy.”

Hulali Kau, a writer and advocate working in Native Hawaiian and environmental law, said, "To anyone that continues to try to frame TMT as a science versus culture argument, I would say that this struggle over the future of Mauna Kea is actually about how we manage resources and align our laws and values of Hawaii to connect a past where the state has subjected its indigenous people to continued mismanagement of it lands with its uncertain future.”

Among many concerns, including the university’s past management of the observation space, Kau said she worries that the TMT will include two 5,000 gallon tanks installed two stories below ground level for chemical and human waste.

Mauna Kea, a conservation district, is home to the largest aquifer in Hawaii, she said. “There are still questions as to the environmental consequences.”

Kau noted that the university was previously embroiled in an indigenous space dispute, when it attempted to patent three strains of taro, or “kalo,” a popular food source. It finally dropped the patents several years later, in 2006.

Other institutions are implicated in telescope debate. There are petitions to divest Canada’s research funding from the telescope, for example. In response to such calls, Vivek Goel, vice president of research and innovation and strategic initiatives at the University of Toronto, released a statement saying that the institution “does not condone the use of police force in furthering its research objectives.” Goel said he’d conveyed those views through the Association of Canadian Universities for Research in Astronomy.

“We know through our own Canadian experience that a commitment to truth and reconciliation impels us to consult and engage with indigenous communities and to work collaboratively towards change,” he added. “We must work to uphold those principles as we engage with indigenous communities beyond our borders as well as within them.”

Noelani Goodyear-Kaopua, associate professor of political science at Hawaii, chained herself to a cattle guard during the first day of protests last week, in preparation for any engagement with law enforcement.

She said that “in no framework of ethical research is it acceptable to arrest dozens of people to set up research infrastructure and conduct research. Peaceful coexistence does not involve calling out police forces from multiple islands, tactical teams and the National Guard.”

And yet, she said, that is what the university, state and TMT partners “are supporting at this moment.”