You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Nature

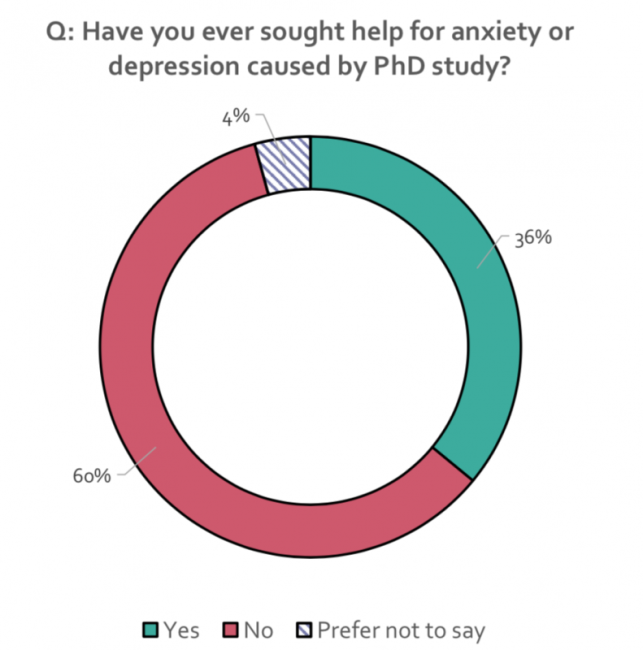

More than a third of Ph.D. students have sought help for anxiety or depression caused by Ph.D. study, according to results of a global survey of 6,300 students from Nature.

Thirty-six percent is a very large share, considering that many students who suffer don’t reach out for help. Still, the figure parallels those found by other studies on the topic. A 2018 study of mostly Ph.D. students, for instance, found that 39 percent of respondents scored in the moderate-to-severe depression range. That’s compared to 6 percent of the general population measured with the same scale.

Nature’s survey of graduate students of different backgrounds and fields is its fifth in a decade. It asked about a range of issues, from planned career paths to work hours to overall program satisfaction. But the data on mental health, including a question asked of all respondents for the first time this year, are particularly alarming -- even as they add to our vital understanding of a serious problem.

“Sadly, the findings are very in line with what we hear, and what we ourselves experience,” said Kaylynne M. Glover, director of legislative affairs at the National Association of Graduate and Professional Students, an advocacy organization.

Calling graduate education “systemically abusive,” Glover said it's “a problem that crosses cities and cultures, and it affects students from low-income and marginalized backgrounds the worst.”

According to Nature’s survey, of those who sought mental health treatment or assistance, 43 percent did so at their Ph.D. institutions. About 26 percent who did said it was helpful. Eighteen percent said they didn’t feel supported. Nine percent said they wanted to seek help but that there was none available on their campus.

Additional qualitative data revealed that mental health support was usually available at Ph.D. institutions, but students had to look for it -- meaning it wasn’t promoted around campus, including by advisers. When help was available, student reported long wait times and a lack of available, affordable counselors.

Satisfaction Linked to Adviser Relationships

Not all responses pointed to problems. Seventy-four percent of respondents were satisfied or very satisfied with their decision to pursue a Ph.D. They were most likely to report enjoying the following aspects of the experience: intellectual challenge; working with smart, interesting people; the academic environment and creativity.

Similarly, 71 percent of respondents said they were satisfied with their time in their programs. Factors strongly correlating with overall satisfaction include number of publications, work-life balance and, especially, the adviser-advisee relationship.

As one student said in an open comment section, success in academe “highly depends on lab/supervisor. A good supervisor can either make you happy during your Ph.D. journey or destroy your life/career.”

Another said, “The academic system doesn't always help the position of the Ph.D. student. The Ph.D. student is very dependent on their supervisor(s) and this means that a good relationship with your supervisor is a necessity for an enjoyable Ph.D. experience. I’m lucky that I have a good relationship, however I’ve seen plenty examples where this isn't the case.”

Some 53 respondents who are dissatisfied over all with their Ph.D. experience are dissatisfied with that relationship. Half of students said they got less than an hour of one-on-one time with their advisers per week. Thirty-five percent got one to three hours, and 12 percent got more than three hours.

Nearly one-quarter of students said they’d change principal investigators (typically advisers) if they could. About 8 percent of students said they wouldn’t pursue the Ph.D. at all, if granted a do-over.

Bullying

Another big problem for students was what they considered bullying -- especially by supervisors. Twenty-one percent of respondents said they’d been bullied in their programs. Of those, 48 percent said their supervisor was the perpetrator.

Less commonly, but still in many instances, other students did the bullying.

Two recent cases illustrate how this can happen. At the University of Wisconsin at Madison, for instance, an engineering graduate student named John Brady died by suicide after seven years under the supervision of a professor who was found to have berated, demeaned and threatened students. And at Arizona State University, the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights is investigating a female engineering student’s complaint that men in her lab turned against her after she reported their adviser for sexual harassment.

According to additional qualitative data from Nature, instances of bullying by advisers or supervisors included acting aggressively, asking students to do work unrelated to their programs or being overly critical. Over half of those bullied said they’d felt unable to speak out. Reasons included fear of repercussions and not having an anonymous mechanism for doing so.

Glover, of the national grad student association, described her own past experiences with a difficult adviser and how the typical single mentor-mentee power dynamic of graduate education makes students so vulnerable.

“Undergraduates aren't directly tied to a single faculty member who controls their lives, but we are,” she said. “We can't change majors or even transfer programs,” or just “change jobs.” Instead, she said, “We’re getting training on a specific skill in a specific area, and for many of us, there's only a handful of people in the country who we can work with. That means that we either put up with it or we drop out, and dropping out puts our financial future at serious risk.”

Twenty-one percent of students said they’d also been harassed or discriminated against in their programs. The reported discrimination, in order of prevalence, related to gender, race, age, sex (sexual harassment), religion, disability and LGBTQ status. The overwhelming majority of respondents who reported gender discrimination and sexual harassment were women. As Nature’s was a global survey, sexual harassment was most prevalent in North and Central America.

One student commented, “The academic system needs a drastic overhaul. It has become a corrupt and abusive system. I would like to see major reforms at every single level.”

What Ph.D. Students Worry About

Asked to rate their level of satisfaction with various factors, students said they were most pleased with their degree of independence, relationship with their supervisor and their ability to attend and present at meetings and conferences.

Students were least satisfied with career pathway guidance, number of publications, work-life balance, benefits and stipend amounts. Funding dissatisfaction was most common among those students 35 or older.

About 45 percent of students said their satisfaction level had decreased since the start of graduate school. Thirteen percent were neutral, and 42 percent said the level increased.

As for what they worried about, seventy-nine percent of respondents ranked uncertainty about job or career prospects among their top five concerns. A close second concern (making 78 percent of top-five worry lists) was difficulty maintaining work-life balance. A third worry (74 percent) was the inability to finish one’s studies in the initial time period. And a close fourth concern (70 percent) was the availability of faculty research jobs, beyond postdoctoral positions. Other main worries were financial, at least in part: difficulty of getting research funding and personal finances after the Ph.D.

Midlevel concerns were concern about mental health as a result of Ph.D. study, the large share of Ph.D.s who do multiple postdocs, uncertainty about the value of a doctorate, low recognition of parenting or eldercare responsibilities, and impact of a poor adviser-advisee relationship.

Of least concern to Ph.D.s, at least relatively, were imposter syndrome, politics and student debt during the Ph.D.

Careers Paths and Preparation

Over half of respondents reported that academe was their career destination, with men being more likely to say so than women. Interest in academic research was especially high. Twenty-eight percent said they preferred to work in industry, with European and U.S. respondents being most open to this path. Medical and nonprofit careers rated as least appealing careers. Sixty-seven percent of respondents said their Ph.D. will improve their job prospects either substantially or dramatically.

Sixty percent of students based their career plans on personal research, with far fewer doing so by observing or talking to their supervisors.

Even with their high hopes for finding work in academe, most Ph.D. students didn’t expect to find faculty jobs immediately. Asked which positions they anticipated taking immediately after the Ph.D., 46 percent said postdocs. Nine percent didn’t know. Just 6 percent said assistant professor. Still, 46 percent of students imagine finding a permanent position within one to two years.

About a third of respondents said they’d learned about nonacademic opportunities from people in their departments. And while half said that department members were open to them pursuing a career outside academe -- good news, given that this historically has been a problem -- just 29 percent said that they’ve been given useful advice in that respect.

In fact, when asked to list the most difficult things for Ph.D. students in their fields, 53 percent of respondents said learning what career possibilities exist. Other top difficulties were related: finding research careers within academe and finding nonresearch careers that use their skills.

Asked to rank various resources as particularly useful in establishing a career, students said grants to help them transition to permanent positions, better data and information on career opportunities, more jobs in academe, and more mentorship.

Around the world, students reported that finding a research job in academe was most challenging. But, again, they also had a lot to say, in write-in comments, about how academe needs a total overhaul.

“Broken from the top down,” one student wrote, for instance. “The pressure to publish to get grants and tenure has filtered down to the Ph.D. student. Faculty push to publish all work rather than support good work that may take more time.”

The student continued, “There is too much pride associated with the number of publications. That number determines which grants you will get and which positions you will get. For those students who do not have successful results in their first two to three years, they are seriously hurt by this.”

Students also tended to report that they were well prepared for careers in involving data analysis and collection, but not well prepared for other aspects of work -- namely managing people and large budgets and developing business plans. In fact, just one-quarter of students said their programs prepared them well for a nonscience, nonresearch career.

Work-Life Balance?

How much time do Ph.D.s spend on their studies and related work per week? Twenty-seven percent of respondents said 41 to 50 hours. One-quarter said 51 to 60 hours, with those under 35 being more likely to spend more time. Most respondents who spent more than 40 hours a week on their Ph.D.s said they were dissatisfied with that.

About half of respondents reported having a “long-hours culture” at their institutions, while 37 percent reported having a good work-life balance.

Nineteen percent of respondents said they had a job outside their programs. Half (53 percent) of those with jobs said they took them on to help make ends meet, while one-quarter said they wanted to develop additional skills. Other reasons included making oneself more attractive to potential employers and broadening one's contact base. Respondents over 35 years of age were significantly more like to have an outside job. Caregivers were also significantly more like to have one.

David Payne, manager editor at Nature, said in a statement that many people assume that being enrolled in a Ph.D. program equals being “set up for life,” but that “sometimes reality can be quite different.”

Surveys such as Nature’s, then, “allow us to understand the challenges students face and can be invaluable to institutions when they are considering the needs of their students.”