You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

HGSU-UAW

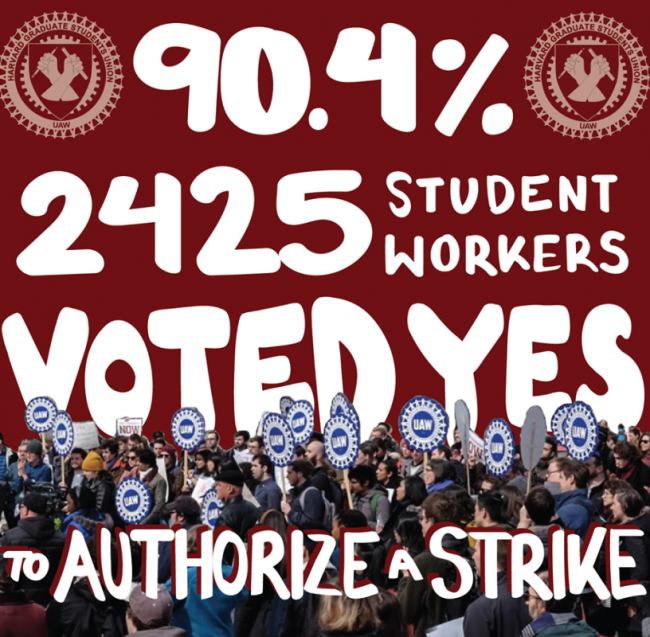

Graduate student workers at Harvard University began an indefinite strike Tuesday, after spending more than a year negotiating a first union contract.

That timeline is not unheard-of for discussions about an initial deal. But graduate students at Harvard, who are affiliated with United Auto Workers, say they’re still fighting for fair pay, comprehensive health care and protections from harassment and discrimination.

Harvard says it’s put forth proposals designed to satisfy each of those demands, and that it has specific concerns about what the union still wants.

Graduate students at private institutions nationwide are waiting to hear more about a proposed rule from the Trump administration’s National Labor Relations Board that would make it even harder for them to form unions. Harvard, however, chose to recognize its union following a majority student vote and began negotiating with it in 2018 -- with the proviso that it would not bargain over issues that are academic in nature.

Harvard and the union have reached tentative agreements thus far on a dozen items, such as employment records, travel and intellectual property, and academic misconduct.

Arguably the biggest items -- pay and health care -- remain unsettled. Harassment protections are at the center of the strike, as well, as graduate student groups increasingly see contracts as a way to address sexual harassment and discrimination issues.

As for pay, Harvard has offered an 8 percent wage increase over three years for salaried student workers and 7 percent for teaching fellows. The university also proposed raising minimum hourly pay to $15 for nonsalaried student workers and $17 per hour for hourly instructional workers.

The graduate student union has asked for more, pointing to Harvard’s relative wealth as an institution and Boston’s high cost of living. Hourly student workers would be set at $25 per hour under one of its proposals, for example. The union also wants more economic stability for teaching fellows, who are often compensated via stipends and discretionary, variable “top-ups.”

Relatedly, the union wants assurances that student workers will not have their financial assistance reduced as a result of winning higher pay via the contract. Harvard finds this idea unacceptable, as financial aid is, in its view, tied to academic and not worker status.

“We have exhausted all other options, and we are frustrated by Harvard’s consistent refusal to provide the basic rights and protections we are seeking,” Jenni Austiff, a Ph.D. candidate in organismic and evolutionary biology, said in a statement.

Graduate students and allies gathered in Harvard Yard for a rally and picket line Tuesday.

As for health care, the union says its member surveys demonstrate the need for more dental, mental health and specialist visits. It also wants hourly student workers to be considered eligible for benefits at a certain threshold.

On Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which prohibits gender-based discrimination, the union seeks an independent arbitration process in these cases. While many student advocates have said that having universities adjudicate their own Title IX cases presents a conflict of interest, Harvard says that an independent process would be inequitable in that it is not accessible to all students. The university also maintains that arbitration is not an investigation.

Harvard said in a statement Tuesday that it remains engaged in negotiations with the union and that a strike “will neither clarify our respective positions nor will it resolve areas of disagreement.”

As for academics during the strike, Harvard said it “takes seriously its responsibility to ensure that all of our students have the opportunity” to complete their work. It will continue to take steps to ensure as little disruption as possible in the semester’s remaining weeks, it said.

Provost Alan Garber said in a memo last week that Harvard recognizes the union’s right to strike and that “both parties have a responsibility to work hard to propose reasonable and mutually agreeable solutions.”

That negotiations have taken so many months thus far is not due to a “lack of good faith” on anyone’s part, he said, but “rather a reflection of the complexity of negotiating a first contract with such a large and diverse union.”