You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

Men are more likely than women to frame their research findings as “novel,” “unique,” “promising” or otherwise positively, according to a new analysis of more than six million articles in the life sciences and academic medicine.

The difference was most pronounced in the highest-impact journals in the study and associated with higher citation counts. So the finding has implications for women’s career progression and gender equity overall. BMJ published the study late Monday.

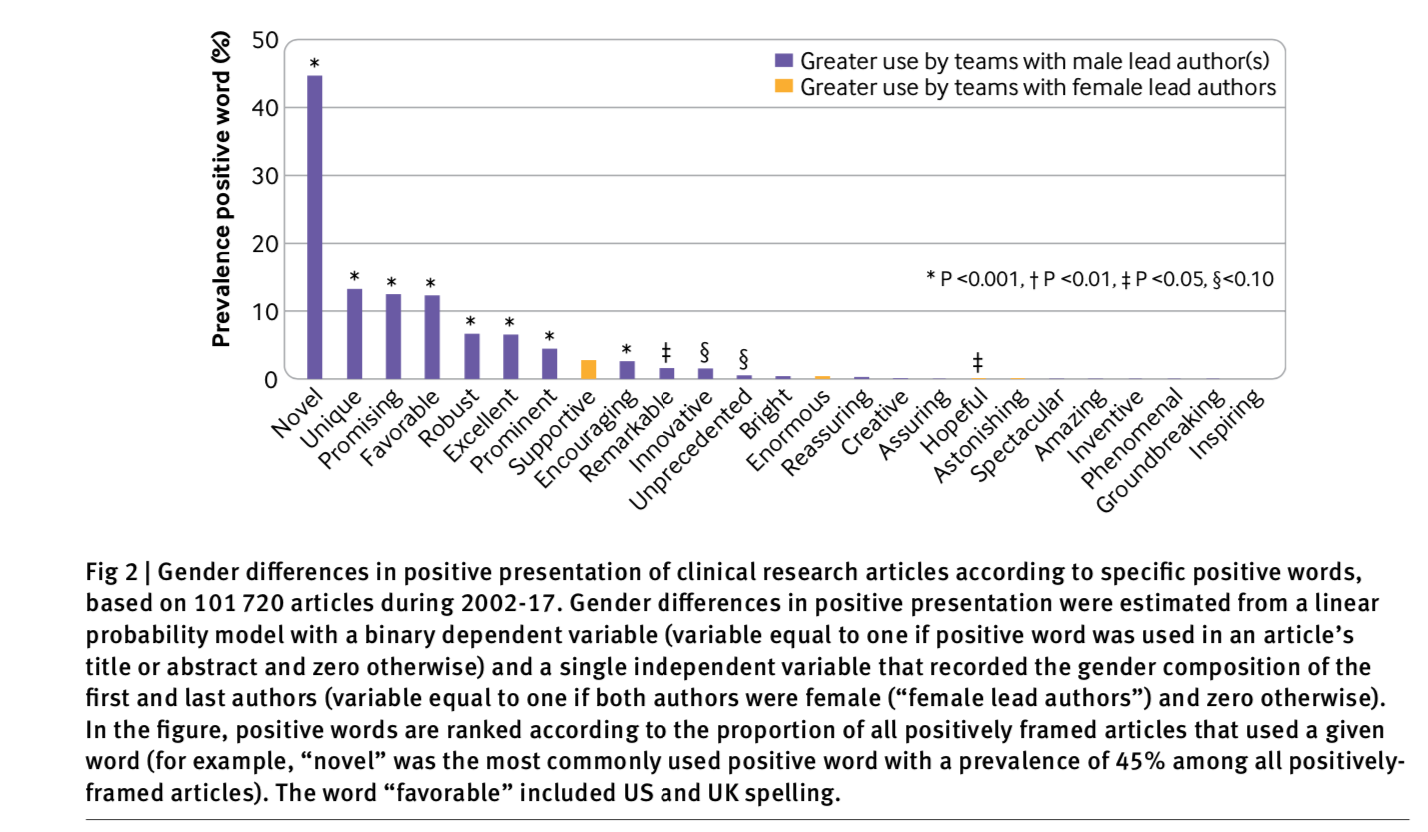

Researchers analyzed titles and abstracts from about 101,720 clinical research articles and 6.2 million articles indexed in PubMed from 2002 to 2017, looking for a possible connection between what they call “self-promotion” and author gender. They screened for 25 words identified by prior research as distinctly positive and frequently used in life sciences articles -- from “robust” to “inspiring” -- and found that articles with both female first and last authors were less likely to use them. That’s compared with articles with a male first or last author, or both.

More precisely, the female-authored articles used at least one of the 25 positive terms in 10.9 percent of titles or abstracts versus 12.2 percent of the male-authored articles, for a 12.3 percent relative difference.

In journals determined to be high impact, that difference shot up to 21.4 percent. Positive framing also was associated with 9.4 percent more subsequent citations and 13 percent more citations in high-impact clinical journals, in particular. The results were consistent even when controlling for the specific journal, the journal’s impact factor, scientific field and year of publication.

Source: Marc Lerchenmueller, Olav Sorenson and Anupam B. Jena

“Women remain underrepresented in academic medicine and the life sciences more broadly,” earning less than men and receiving fewer research grants and citations than their male colleagues, the study says, citing prior research. And while the new analysis is limited in that it is observational, one mechanism that may contribute to these gender gaps “is differences in the extent to which women promote their research accomplishments relative to men.”

“Self-promotion” may take different forms, including using social media to call attention to one’s research or presenting at scientific meetings, the authors wrote. And because these opportunities occur more frequently than, say, hiring and promotion decisions or salary negotiations, these “features may render self-promotion a powerful tool for gradually challenging gender stereotypes.”

Co-author Olav Sorenson, Frederick Frank and Mary C. Tanner Professor of Management at Yale University, said that the 12 percent gap “by itself might not seem like such a concern.” But it’s important to keep in mind that such a “penalty compounds other gender gaps.” For example, one of Sorenson’s own prior studies found that women received 25 percent less credit than men for the citations they receive, in terms of winning grants.

If women also receive fewer citations “because they refrain from self-promoting their research,” Sorenson said, “then they pay a double penalty.”

The underlying causes of the gender gap in self-promotion are surely social in nature, not something originating in the sciences. Sorenson said he and his colleagues believe that their findings would generalize “to a wide variety of fields.” He pointed, for example, to a 2017 study led by Molly King, assistant professor of sociology at Santa Clara University, finding that men across a number of fields cited their own papers 56 percent more than women did. Looking only at the last two decades of data, through 2011, men self-cited 70 percent more than women did.

In an accompanying editorial to the BMJ paper, Reshma Jagsi, Newman Family Professor and director of the Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences in Medicine at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, and Julie K. Silver, associate professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Harvard University, said that girls are “socialized from childhood to act with modesty and take up little space, and this norm affects adult behaviors that can have meaningful consequences.” Moreover, they wrote, “the paucity of senior female role models who have been celebrated for their contributions likely contributes to women experiencing more than their share of self doubt and may even lead some women to develop ‘impostor syndrome’ (which can affect all genders) and question their self worth.”

Is the answer for women to self-promote more, or for men to exercise more restraint? Jagsi and Silver caution against a “fix the women” approach, which lacks "understanding of the current evidence base on gender equity." Instead, they favor "fixing the systems that support various types of bias including implicit (unconscious), structural, and organizational." It may also be useful for journal editors to "work together to establish common standards and more transparent, shared expectations regarding the strength of evidence required to support the use of certain terms when framing research findings.”

Researchers selecting citations should also be aware of the "biases that can be introduced throughout the research and publication process,” Jagsi and Silver wrote. Producers and consumers of science alike “must be vigilant in evaluating the quality of the analyses and data presented to us by our colleagues. We must all work to counteract bias in order to optimally advance science.”