You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

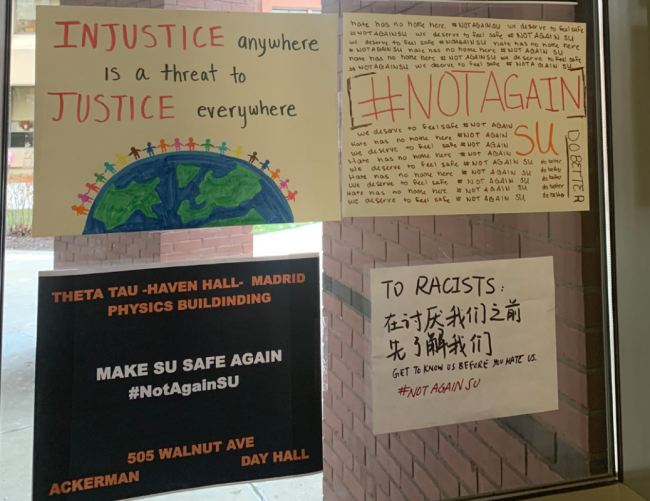

Student signs posted on the Syracuse campus in November, in response to racist incidents

Twitter/@zoeselesi

Syracuse University saw a spate of racist incidents last semester -- some 16 over a few weeks in November alone. Students reported hearing ethnic slurs shouted from dorm windows and otherwise being harassed, along with seeing hateful graffiti and a swastika drawn in the snow. The Federal Bureau of Investigation also looked into a white supremacist manifesto that was posted to an online Greek life forum.

Students protested, including by occupying a campus building for a week, as faculty members pushed for change. In response, Syracuse announced a list of new diversity, inclusion and security initiatives. The university also promised to rethink its one-credit first-year seminar, SEM 100, and to work toward building a complementary, three-credit requirement for more advanced students.

Many professors believe Syracuse's response should go further, however. They believe the moment demands a deeper rethinking of the curriculum, universitywide.

Seeking an 'Extensive Liberal Arts Core'

Their idea is that a liberal arts education steeped in discussions of human differences is the best defense against ignorance. But at the very least, said Biko Gray, assistant professor of religion, “if we’re doing this, no one can feign ignorance about these issues. ‘That was a joke’ is no longer a defense.”

Gray, along with his department colleague Virginia Burrus, the Bishop W. Earl Ledden Professor of Religion, co-wrote a faculty statement to this effect. It has since been signed by 146 other professors.

The statement, sent to Syracuse’s central administration for consideration, says that the university is caught up in a moment of “great anguish” but also “unusual clarity and possibility.” That moment “clarified that this institution struggles with -- and therefore suffers from -- a woeful lack of attention to, if not outright neglect of, the critical, conceptual, and ethical importance of the humanities, arts and social sciences.”

The “obligation to teach our students to think critically and constructively about the complexities of human difference can be best addressed through an extensive liberal arts core curriculum attuned to issues of difference and diversity and required university-wide for all undergraduates,” the statement asserts. “Anything less, such as the single-course solution represented by SEM 100 in whatever guise, will be inadequate as other than a transitional measure and ultimately ineffective in shifting the campus climate of discrimination.”

Currently, arts and sciences students must take two courses from a list of approved classes to satisfy a requirement in critical reflections on ethical and social issues. This is not standardized across campus programs and colleges, however, and what the faculty statement proposes -- though not in any detail -- is a larger core curriculum.

Crucially, the faculty statement says, “Support for such a liberal arts core curriculum requires nurturing, strengthening and expanding the faculty in the humanities, arts, and social sciences.” It requires “actively cultivating a diverse and inclusive faculty across the university, since the bodies and identities of teachers are a crucial part of any curriculum,” and it requires overcoming barriers to this kind of change.

In particular, the statement expresses concern that the university’s cluster hiring initiative favors the natural sciences and steers “resources away from the humanities, arts, and social sciences, as well as from efforts to build faculty diversity.” Further, Syracuse’s responsibility-centered funding model, “which encourages the various schools to compete with one another for students, impedes a university-wide commitment to a liberal arts core curriculum.”

Finally, the statement reads, “we believe that opening up lines of communication between the faculty and the Board of Trustees is crucial to the success of the university in effecting needed change.”

While “no group can claim to represent the voices of all faculty members,” there are “some of us who feel an urgent need to think, speak and act collectively.”

Although the statement ends with an invitation for all faculty colleagues, “across schools, divisions, departments and disciplines” to “join us in our efforts,” almost all the statement’s signers work in the arts, humanities, social sciences and communications.

Gray said the statement was shared network-style, not formally sent to every professor on the faculty. This likely explains, in part, the lack of signatures from faculty members in the sciences, technology, engineering and math. Still, for a letter calling for universitywide engagement in discussions about the liberal arts and diversity, the resulting gap in signatures is hard to ignore.

Discussions about diversity and inclusion with respect to the curriculum are, on so many campuses, taken up by humanities and social sciences faculties. The STEM fields have clearly stepped up in terms of valuing diversity in terms of representation, or who is doing the math and science, with hiring initiatives that aim to increase the share of underrepresented minority faculty members. But this kind of diversity is one part of the bigger puzzle, and one that is complicated by the concern -- expressed in the faculty statement -- that STEM hiring is diverting institutional resources away from the fields most obviously equipped to teach students about human difference.

Another question is whether the STEM fields should be doing more to directly engage students in these issues.

Two Cultures?

“The assumption is that the sciences are value-neutral set of disciplines,” Gray said. And yet the histories of so many fields, from technology to medicine -- think Henrietta Lacks, the Tuskegee syphilis experiment and nuclear testing in the Pacific -- are rife with discrimination. While Gray said he didn’t expect his STEM colleagues to fundamentally alter the way they run their programs, he said students might benefit from being asked to “wrestle” with some of these issues, as they do in other disciplines.

Steven Diaz, a professor of math and a member of Syracuse’s University Senate curriculum committee, said he was familiar with the statement but didn’t sign it. He also said it wasn’t the first time that a universitywide liberal arts core had been proposed, but that it would be very hard to fit more requirements into certain pre-professional programs. This, of course, is a common problem for curricular revision committees, as students in engineering and other fields that are accredited by outside disciplinary bodies typically have little room for additional requirements.

Diaz said that he isn’t personally a fan of large core curricula. As for incorporating questions of diversity and inclusion into math, Diaz said he often teaches a history of math course that demonstrates how math emerged in many world cultures. Unfortunately, he said, there isn’t typically time in the course to grapple in any depth with how the field came to be dominated by white men in the modern era.

There’s another problem with asking nonexperts on diversity and inclusion to embrace discussions of it, Diaz said: they might not know how, or even be afraid, to do it. That goes for students, too, he added, in that those who don’t want to take liberal arts courses might resent having to do so under any new framework, and thus not absorb the point.

“I don’t really know how to cure the problems we have, but I’m not sure taking more courses would help,” Diaz said. “It’s also easy to develop an attitude that if everyone would just study more of this, then the world would be a better place. There’s a lot of that going on with humanities. I think the world be a better place if everybody did a lot more math, but I don’t think that’s the way to go.”

A Diversity Requirement

As was noted in Syracuse’s announcement about the new initiatives, the university is currently revising the one-credit freshman seminar that has been required since 2018. Jeffrey Mangram, an associate professor of education who is leading that effort, said the focus now is “trying to make the material more developmentally appropriate for students.” Earlier iterations of the seminar used books such as Trevor Noah’s memoir on growing up interracial in South Africa, Mangram said, but future versions will be based more on podcasts, TED talks and articles, “trying to think about diversity, inclusion, equity and excellence in different ways.”

Starting in 2021, students beyond their freshman year will be required to choose a three-credit diversity requirement from a list of preapproved courses within departments.

As for diversity and inclusion in STEM, Mangram said it’s important to think about how equitable pedagogical practices round out other goals. Even in those fields that don’t automatically lend themselves to learning about diversity, he said, it’s important that all students feel included, able to participate and that there is room for diverse perspectives.

Gareth Fisher, an associate professor of religion who signed the faculty statement, said he understood SEM 100 to be something of a “stopgap” answer to the university’s ongoing diversity concerns, but that any real answer “has to be built in the curriculum more.”

Already, he said, SEM 100 has seen staffing shortages, and some Chinese students have reported experiencing discrimination by instructors within these very courses. So instead of a “force-fed” take on diversity, students need the kind of depth and nuance that is embedded in a universitywide liberal arts core. That is true for arts and sciences students and pre-professional students alike.

“What they come away with is knowledge about the world and how to cope, and the important questions about diversity that anyone who is a professional in our society is going to be forced deal with,” he said.

Syracuse did not comment directly on the faculty statement.

Beyond Syracuse

While things at that campus took an especially dark turn earlier this academic year, most institutions are dealing with questions of diversity and inclusion and how they relate to the curriculum.

Yale University, for instance, recently announced that it was ending a longtime survey course in art history, HSAR 115, which covers Western art from the Renaissance onward.

Some commentators have criticized the decision, suggesting that Yale cowed to a deconstructionist mob. This fits in with larger critiques of changes to the curriculum as students demand diversity, equity and inclusion.

The National Association of Scholars recently published a report, written by Stanley Kurtz, asserting that both Western civilization and American exceptionalism are very real things, not constructs. It makes a case for reading the great books and restoring our “lost history.”

David Randall, director of research at the national association, said that losing a Western art history survey means the loss of “knowledge of the tradition itself, the continuous conversation of Western artists with their predecessors, and their assimilation of and influence upon rival artistic traditions.” Enjoying art for art’s sake also loses out to the political and issues of identity, he said.

Tim Barringer, Paul Mellon Professor of Art at Yale, in a brief email pushed back against what he called “inflammatory” framing of the survey issue in other news coverage. He also shared a department statement about the survey course, explaining that the program is now committed to offering four different introductory courses each year.

“All of these courses, current or future, are designed to introduce the undergraduate with no prior experience of the history of art to art historical looking and thinking,” the statement says. “They also range broadly in terms of geography and chronology. Essential to this decision is the department’s belief that no one survey course taught in the space of a semester could ever be comprehensive, and that no one survey course can be taken as the definitive survey of our discipline.”

What’s interesting about the Syracuse proposal is that it suggests decentralizing the Western perspective, while at the same time exposing many students to the liberal arts who wouldn’t otherwise take these courses. The question for the critics, then, becomes whether it’s a win to have more students studying the great books -- or at least some of them -- even if they’re doing so from a critical perspective.