You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

There were lots of reasons for professors to avoid synchronous instruction at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. Students are scattered across different times zones, their access to computers and reliable internet varies, and everyday schedules have changed. It’s also hard to teach a 10 a.m. class live when you keep getting booted off your own videoconference, for example, or when students don’t show up because they’re caring for their families or have other responsibilities at that time.

Yet synchronous, real-time instruction, typically via videoconferencing, has surged in the past two months. Zoom and other synchronous platforms are popular ways to hold class.

Experts say this isn’t necessarily a bad thing in an emergency situation. Among other benefits, synchronous instruction can provide socially isolated students a schedule and sense of community. But it disadvantages some students, including those with disabilities, and it can also overwhelm professors. Asynchronous instruction, meanwhile -- in which students learn via videos, readings and other media -- is typically self-paced. Transcripts and other learning aids can be made available to some or all students.

So those same experts warn professors who went all synchronous this semester as a survival strategy that future terms will be different. Students will demand a mix of instructional methods if campuses remain closed for summer and fall terms and classes are remote.

“I don’t see it as synchronous versus asynchronous, it’s ‘What’s the right approach for your students or your subject matter?’” said Phil Hill, a partner at MindWires, an ed-tech consultancy. “What I do see is that videoconferencing is overused right now and faculty and schools better rebalance before the fall. They better understand the limitations and back way off of synchronous video and increase the usage of asynchronous tools, because we haven’t seen enough of that.”

Limitations of Synchronous Instruction

The limitations of synchronous video are equity and access, Hill said. Do students have a quiet space and computers with strong internet connections to thrive during live class meetings? A recent study by WhistleOut, for example, found that one-third of adult respondents who transitioned to working or studying from home had been prevented from doing so by weak internet. Two-thirds said their video calls had cut out, frozen or disconnected. Additional concerns include security, such as Zoom-bombing, when trolls crash live classes with offensive content.

Synchronous instruction also doesn’t always offer students with special learning needs or disabilities what they need to learn. Some professors who lecture live record their meetings do post them online afterward, with transcripts and other materials, but not all.

Penny E. MacCormack, chief academic officer at the Association of College and University Educators, which offers a popular course on effective teaching practices and other professional development, said that synchronous class meetings can be “great opportunities for students and instructors to interact and delve into some of the class materials more deeply.” At the same time, she said, “we do need to recognize that being able to meet at a particular time and having the technology available to do so can be challenging for a variety of reasons.”

One approach is using synchronous meetings “sparingly for learning opportunities that truly benefit from that special kind of interaction a Zoom meeting can supply,” MacCormack said, “and make them voluntary so that students who, for any variety of reasons, cannot join don’t feel left out.”

Learning management systems, which are often used to facilitate asynchronous instruction, have seen major increases in usage since the spread of COVID-19 forced U.S. institutions to go remote. But LMS usage hasn't increased nearly as much as synchronous activity in virtual classrooms and videoconferencing. D2L Brightspace’s Virtual Classroom is seeing 25 times more activity than usual, and Blackboard Collaborate's global daily user count increased by 3,600 percent, for example, according to an analysis by Hill.

Zoom usage went up 20-fold. The service doesn’t release education-specific numbers, but there’s been an obvious higher ed boom there and on similar platforms, such a Google Hangouts and Microsoft Teams.

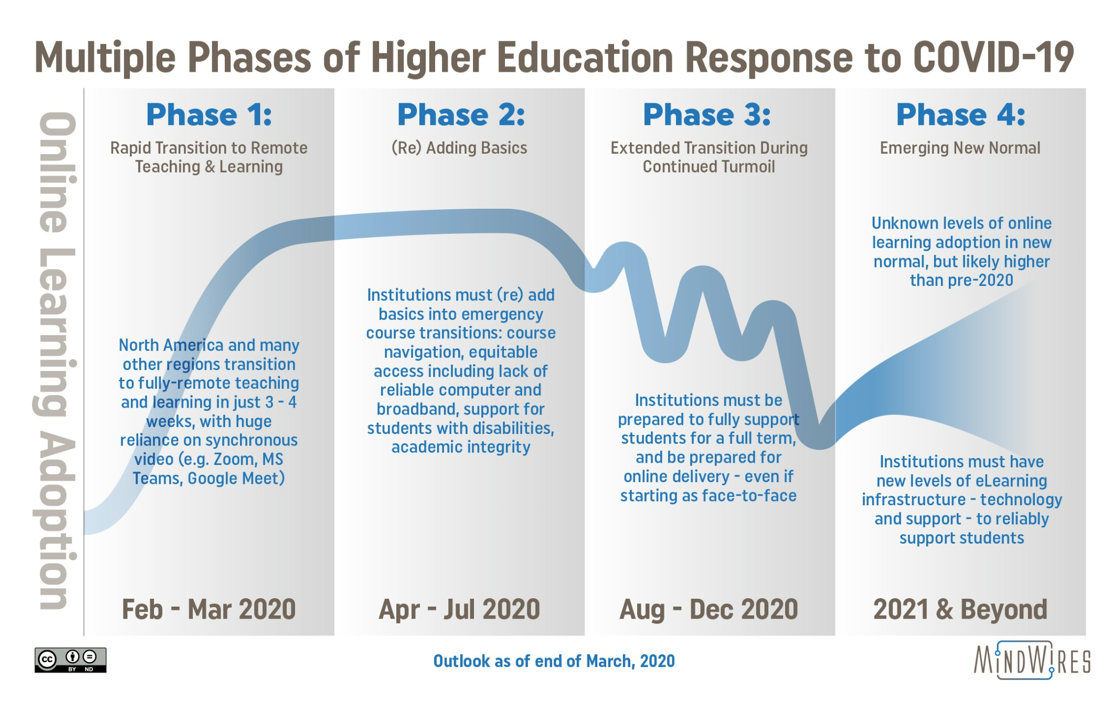

Hill’s analysis says that the videoconference was the defining feature of Phase 1 of the transition to remote teaching and learning. Phase 2, which we're in now, puts a greater emphasis on equity and accessibility. Phase 3, starting in August, entails being able to support students remotely for a full term. Phase 4, in 2021, is a new normal.

Charles Hodges, a professor of leadership, technology and human development at Georgia Southern University, said that in the current “emergency,” delivering lectures via synchronous videoconference “might be a first impulse, if that is what you were planning for your face-to-face classes.”

Now, however, he said, instructors “should be asking themselves questions like, ‘Is it important for the class to meet all together at the same time? Why? Is it reasonable to expect all of my students to be together online at once given what they might be juggling at home now?’”

Seeking a Balance

Maybe synchronous delivery is the “best option for your particular circumstance, but it should be a thoughtful decision considering several factors -- not simply that you think your students need to see your talking head,” Hodges said.

Viviana Pezzullo, a graduate teaching assistant in comparative studies at Florida Atlantic University, is currently teaching both synchronously and asynchronously and has found asynchronous instruction to be most effective in ensuring student success. A lot of prep work is needed, though, she said: video lectures, announcements, assignments and guided group discussions. And because students don’t literally see you, Pezzullo said it’s important to establish a pattern of communication, with announcements posted on a weekly or biweekly basis and outreach to individual students.

Either way, Pezzullo advised posting accessible documents, such as transcripts of lectures, for all students -- not just those who ask for them. Breakout rooms for small-group interaction benefit students in large, synchronous classes, she also advised.

Lauri Mattenson, an instructor of writing and affiliate faculty member in disability studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, said she’s found herself "far more in tune with the diverse needs and preferences of all my students" this term. She's teaching synchronously and using her course website for discussions and the video gallery. In addition to meeting with her classes as a group, Mattenson also meets with students individually and in small groups on Zoom.

Learning From the Crisis

Describing the pandemic as something of an opportunity in this narrow sense, Mattenson said, “There's a shift happening.” Previously, she said via email, “there was a standard format/structure/set of expectations for each class, and ‘accommodations’ were viewed as being designed for a small subset of people with needs.”

Now, there’s a “broader understanding that we are all people with needs and true inclusivity can acknowledge those varying needs without dividing us into categories like normal/abnormal, standard/atypical, etc. The disabled should not be viewed as a singular or ‘deficient’ group.”

Annie Soisson, director of the Center for the Enhancement of Learning and Teaching at Tufts University, said remote teaching during this crisis means “moving more quickly in a direction than we would have otherwise.” Tufts, like most institutions, hasn’t made a decision about whether courses will be in person or not in the fall. Whatever happens, Soisson is encouraging professors to start putting parts of their courses on Canvas, Tufts’s LMS, anyway, as “you have nothing to lose.”

Doing so leaves room for more active learning during class time, which only benefits students, especially minoritized students, she said.

“A lot of things about online teaching make our face-to-face teaching better.”

Socially and emotionally, Soisson said, “The synchronous part has been really important for many of those students and help them avoid feelings of isolation and the loss they felt being ripped from the academic environment and their friends and supports.”

As for asynchronous instruction, Soisson said that students need high executive functioning skills to set schedules for themselves to work when they’re used to a much more regular rhythm: class at a certain time two or three times a week.

Barbara Lockee, a professor of education and faculty fellow in the Office of the Provost at Virginia Tech, also said some learners need more structure than others, and that undergraduate learners, in particular, may be “more accustomed to the usual routines and instructional traditions associated with classroom-based learning experiences.”

Synchronous delivery with tools such as Zoom more closely approximates that environment, but flexibility is essential in the current context, Lockee said. So a “blended strategy” that incorporates both synchronous and asynchronous activities can serve to “keep learners on track, while providing some flexibility in the engagement with other content or assessments.”

Several campuses have announced they’re looking into boot camp-style online instructional training for faculty members over the summer. Hill was somewhat skeptical of that idea, saying that institutions best positioned for this era had a "culture" of online teaching and learning in general prior to the pandemic.

Zoom Fatigue, and a False Binary?

Synchronous video instruction might be easier on its face for faculty members. But they’re also inundated with additional videoconferencing demands, Lockee said: individual advising, research activities, administrative meetings, crisis response planning and more.

The Zoom boom has added to the faculty workload to the point of becoming an “impediment to instructional planning and the completion of class activities related to feedback and grading,” she warned. “With all course activities being offered online, class time is now 24-7, and the demands on faculty are exhausting.”

Many professor report Zoom fatigue. Susan Blum, a professor of anthropology at the University of Notre Dame, explored just why videoconferencing feels so much more exhausting than classroom teaching in a widely read column for Inside Higher Ed.

“I’m on high alert, I’m vigilant the whole time,” Blum said in an interview. “Every sense is recruited to try and make sure it’s working well.”

She rarely lectures in her ordinary classes but has done so on Zoom. That’s not all she’s doing synchronously or asynchronously, however. She’s leading breakout discussions, having project teams read each other’s writing and more.

Blum said she doesn’t like to treat synchronous and asynchronous instruction as two wildly different ideas, anyway, arguing that professors have long taught in a “blended” manner.

Arguably, a blend of synchronous and asynchronous instruction is a kind of flipped classroom, in which students front-load content outside class and reserve actual class time for the application of that content through active learning exercises.

“Learning is not just something that happens when a teacher is watching,” Blum said.

Similarly, Hodges, of Georgia Southern, said that an asynchronous delivery format “can allow students to dig deeper into readings, questions and assignments before responding in a synchronous format.”

More than attaching labels to how professors deliver content, Blum had different, perhaps bigger questions on her mind one recent afternoon.

“The key is to figure out, what are we really trying to accomplish? What do students need to accomplish, without just assuming that you have to stick to the syllabus and follow the textbook and the schedule and everything?” she asked.