You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

istockphoto.com/peopleimages

Students continue to have a conflicting view of how speech should be managed on college campuses. A majority of them say certain offensive language should be restricted, but they also agree it is important to be exposed to all types of speech during college, according to a new survey report.

The report, released Tuesday and based on a survey conducted in 2019 by the Knight Foundation and Gallup, is the third in a series of reports that measures students' knowledge of and value for the First Amendment. The survey included responses from 3,319 students aged 18 to 24 from 24 U.S. institutions, including four historically black colleges and universities, 15 public and nine private institutions.

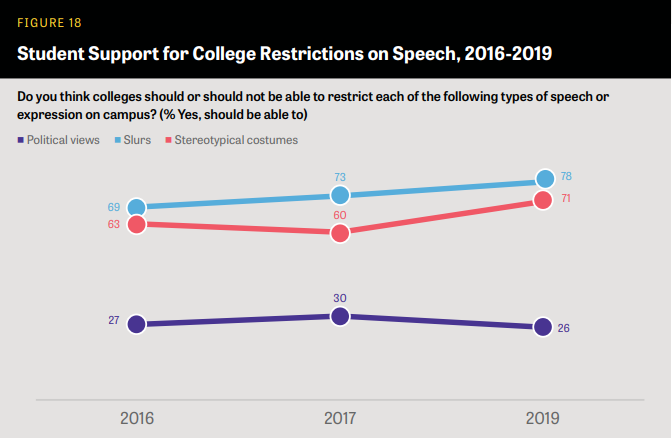

A continuing trend is the disconnect in students’ “theoretical” or “philosophical” view in favor of First Amendment protections on campus, which shifts when asked about specific offensive behavior, said Jeffrey Jones, senior research consultant for Gallup. For example, 78 percent of students said they believe colleges should be able to restrict the use of racial slurs and 71 percent favored banning the wearing of costumes that stereotype certain ethnic and racial groups. The support for costume bans reflects an 11 percent increase from 2017, according to the report.

A continuing trend is the disconnect in students’ “theoretical” or “philosophical” view in favor of First Amendment protections on campus, which shifts when asked about specific offensive behavior, said Jeffrey Jones, senior research consultant for Gallup. For example, 78 percent of students said they believe colleges should be able to restrict the use of racial slurs and 71 percent favored banning the wearing of costumes that stereotype certain ethnic and racial groups. The support for costume bans reflects an 11 percent increase from 2017, according to the report.

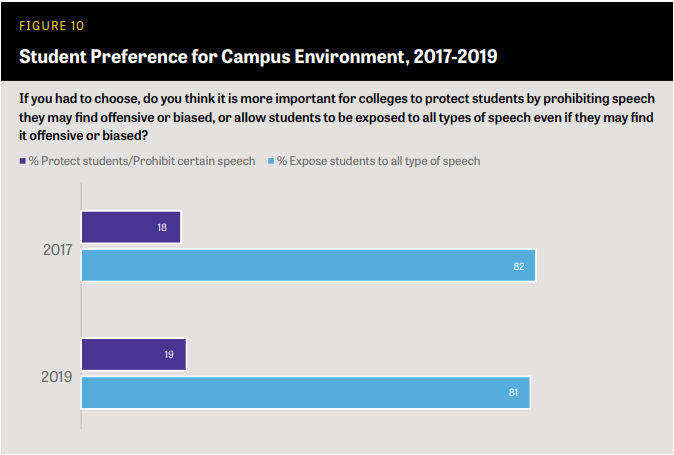

However, when asked, “Do you think it is more important for colleges to protect students by prohibiting speech they may find offensive or biased, or allow students to be exposed to all types of speech,” students overwhelmingly supported colleges upholding the right to free speech, even if it’s “offensive or biased,” the report said. The varied responses to both theoretical and more literal questions about the First Amendment show where diversity and inclusion and free speech goals can butt heads, Jones said.

However, when asked, “Do you think it is more important for colleges to protect students by prohibiting speech they may find offensive or biased, or allow students to be exposed to all types of speech,” students overwhelmingly supported colleges upholding the right to free speech, even if it’s “offensive or biased,” the report said. The varied responses to both theoretical and more literal questions about the First Amendment show where diversity and inclusion and free speech goals can butt heads, Jones said.

“People are conflicted about justifiable and worthy goals that sometimes don’t coexist very well,” Jones said.

In the 2017 survey, students were asked to weigh the importance of diversity and inclusion directly against the protection of free speech rights, which ended up being a “controversial question,” said Evette Alexander, director of learning and impact for the Knight Foundation. When asked to choose between a diverse and inclusive society and protecting free speech rights, 53 percent of students chose diversity, according to the 2017 results. But this question created “a false choice that maybe doesn’t exist” for students who are shown to value both diversity and inclusion and free speech equally, Alexander said.

“They’re trying to reconcile these two values and provide reprieve for students who may need it more,” she said. “In a campus environment, one of the goals is a good learning environment for all people, so I think they have that in mind as well.”

Instead of presuming that diversity and inclusion and free speech protections on campus already conflict, researchers decided to ask students on the 2019 survey how often the two “come into conflict,” Jones said. They found that 27 percent of students believe they “frequently” conflict and 49 percent said they do “occasionally,” according to the report.

Another indication of this conflict is how students of color did not feel as strongly as white students that the First Amendment protects them, Alexander said. According to the report, only one-quarter of black students said they “strongly agree” that the First Amendment protects “people like me” while more than half of white students surveyed said so. There’s an “underlying disconnect between what the First Amendment is supposed to do” and students’ perspective of it, Alexander said.

“Our hope is for anyone who’s promoting a campus environment where there’s open inquiry for speech, be aware that different types of students are experiencing speech differently,” Alexander said.

But possibly even more vital than campus environments is the landscape for free speech on social media platforms, Alexander said. Fifty-eight percent of students surveyed said most discussion of political and social ideas among peers takes place on social media, rather than face-to-face spaces on campus, such as classrooms. This figure has remained almost unchanged since the 2017 survey, according to the report, and it’s concerning because social media is considered a private entity and does not have the free speech protections that exist in government-controlled spaces, such as public colleges, Alexander said.

Students also reported in Knight/Gallup surveys that dialogue on social media has grown less civil from 2016 to 2019. Only 29 percent of students in the 2019 survey “strongly” or “somewhat” agreed that dialogue on social media is “usually civil” compared to 41 percent in 2016. Alexander also noted that the coronavirus pandemic is likely to dramatically increase the amount of student discourse occurring online.

“Of course now with the flight of students from campuses to their homes and remote learning, all of this is happening almost exclusively online,” she said. “Removing the face-to-face component of these conversations is a loss.”