You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Student services team at the College of Southern Maryland holds a drive-through food distribution event at its Hughesville campus for students struggling financially and experiencing food insecurity during the pandemic.

Courtesy of the College of Southern Maryland

Judith Moore, a mathematics professor at the College of Southern Maryland, was overseeing a test last term in the way it’s done these days. She kept an eye on the images of her students on her screen as the cameras on their computers showed them taking the tests from kitchen tables and bedrooms of wherever they happened to be. But she noticed one woman who appeared to be in distress.

"She kept putting her face in her hands," said Moore. "She had this look of intense frustration, like she was trying not to cry."

So Moore messaged her to ask what was wrong. What the student messaged back was indicative of the challenges often faced by students of color. Because the students are more likely to come from lower-income backgrounds and families who can’t afford to help them pay the bills, they are more likely to have to work or raise children while they go to class.The woman was taking the test after working all night. She was exhausted and stressed It was all too much.

Students who attend institutions that disproportionately serve more students of color, including community colleges and historically Black colleges and universities, are less likely to graduate than students at universities where students tend to be richer and, yes, white.

But several studies show colleges that serve greater percentages of students of color, and are more likely to enroll students who struggle with poverty and other inequities in succeeding in college, have less to spend for each of their students than better-heeled institutions.

During the class at the College of Southern Maryland, a community college where 44 percent of the students are of color, Moore told the student to just forget about the test and go home. She let her take it the next morning. And the student passed.

"What would I do with more money? I ask myself that all the time."

-- Maureen Murphy

Moore flagged the student to her advisers at the college as someone who likely needed help. But just one academic adviser is tasked with helping hundreds or thousands of students at each of the college’s campuses. “They’re overwhelmed,” Moore said.

Recently the college’s president, Maureen Murphy, was asked about the disparity in funding that exists in higher education.

“What would I do with more money?” Murphy said. “I ask myself that all the time.”

Six years ago, 1,165 freshmen enrolled at the college. Three years later, only 28 percent of those students had graduated, though another 21 percent had transferred to other institutions. Murphy said she would use any additional funding the college got to increase financial assistance for Black students, who are more likely than white students to have to balance school with working full-time, or for Black, Latino and Native American students, who are more likely to take care of children while going to college.

Little Progress

While the killing of George Floyd has prompted national soul-searching about racial equity, a number of studies show the nation is making little progress in undoing the decades-long underfunding of colleges with larger percentages of students of color.

According to a study last year by the Institute for College Access and Success, 54 percent of Black, Latino, American Indian/Alaska Native and Pacific Islander students who attended public colleges in 2016-17 were enrolled at two-year institutions. In comparison, 23 percent of those attending institutions that offer master's degrees that year were people of color.

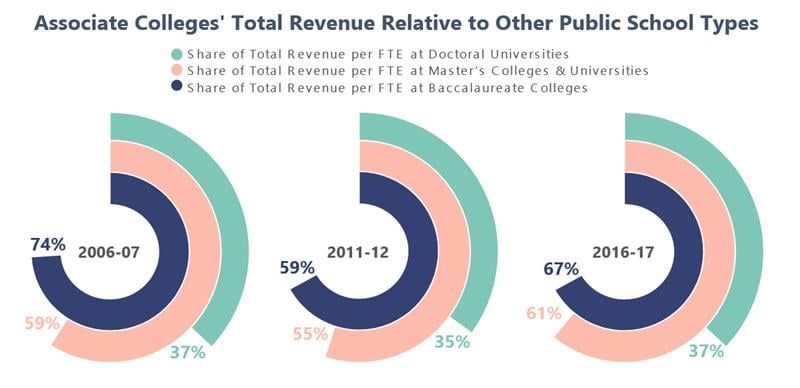

But funding for two-year colleges, such as the College of Southern Maryland , has lagged behind. In 2006-07, community colleges had only 59 cents for every dollar institutions offering master's degrees could spend, according to the TICAS study.

By the 2016-17 academic year, the gap had narrowed -- slightly. Community colleges could now spend 61 cents for every dollar institutions offering master’s degrees could spend -- two pennies more than a decade earlier, the TICAS study found.

In 2006-07, community colleges brought in 37 percent of the revenue of doctoral institutions. A decade later, the sector had 37 cents for every dollar doctoral universities had.

As the nation again enters another recession, it’s too early to tell what the disparity will look like when it ends.

But there’s not much optimism the gap will narrow.

Denisa Gandara, assistant professor of education policy at Southern Methodist University, noted that if previous recessions are a guide, more students will enroll in community colleges while funding will likely fall, meaning the colleges will have even less to spend for each student.

“We’re very concerned about what’s potentially up ahead. Some states are cutting community colleges significantly,” said David Baime, senior vice president for government relations and policy analysis for the American Association of Community Colleges. “The expectations are that there will be very large budget cuts as the economy slides into a recession.”

In addition, Baime said, the inequities have continued in the financial help Congress is giving colleges to deal with the financial blows they are taking from the closure of campuses during the pandemic. That's because the $14 billion in aid for higher education in the CARES Act was doled out based on the number of full-time-equivalent students enrolled by institutions.

"We’re very concerned about what’s potentially up ahead. Some states are cutting community colleges significantly."

-- David Baime

The larger public institutions that benefit from this method say they have more costs during the pandemic, including having had to refund room and board fees to students when campuses closed and sanitizing residence halls as they try to reopen. But Baime says the funding formula works against community colleges because they are more likely to enroll students who attend half-time while they go to work or take care of their kids.

In fact, community colleges received only about 54 cents for every dollar received by public four-year institutions, according to an analysis by Ben Miller, vice president for postsecondary education at the left-leaning Center for American Progress.

What’s needed to finally bring about some semblance of equity, said Shaun R. Harper, head of the University of Southern California’s Race and Equity Center, is to once and for all level the playing field between what colleges with more students of color and less diverse universities can spend to help more students graduate.

In a 2018 study, the Center for American Progress put the figure at $5 billion annually to raise what’s being spent to educate each Black and Latinx student at all types of institutions to the same level as white students.

As out of reach as racial equity may seem at times, that figure doesn’t appear to be out of the question, advocates said, at a time when Congress is considering spending at least $500 billion on another stimulus package.

"There is no question we can afford it. President Trump cut the corporate rate at a cost of $1.3 trillion [over a decade]. If we let corporations keep only 96 percent of this money, we could invest $5 billion more a year in our colleges."

-- James Kvaal

Or, in comparison, Joe Biden, the Democratic nominee for president, has adopted Bernie Sanders’s plan to make two-year colleges free, as well as to eliminate tuition at public four-year colleges and public and private HBCUs -- a proposal that would cost an estimated $48 billion annually.

“There is no question we can afford it. President Trump cut the corporate rate at a cost of $1.3 trillion [over a decade]. If we let corporations keep only 96 percent of this money, we could invest $5 billion more a year in our colleges,” said James Kvaal, president of TICAS and the former deputy domestic policy adviser during the Obama administration.

What Would Funding Equity Look Like?

But to many, even spending as much to educate students of color as white students wouldn’t undo decades of underfunding.

Certainly it would help, said Quinton Ross, president of Alabama State University. But such a shift wouldn’t be enough to undo the fact that HBCUs like Alabama State do not have the same level of facilities that research institutions (which enroll more white students) use to help bring in more research money. As a result, HBCUs often lose out to larger institutions in getting government contracts.

His students also are more likely to have arrived on campus after suffering through the inequities of the K-12 system, and often need more help than students from well-funded school districts.

“It wouldn’t be equity,” Ross said of leveling spending. “Because we’re already behind. We need more.”

David Sheppard, chief legal officer and chief of staff for the Thurgood Marshall College Fund, which supports HBCUs, said the federal government and states clearly have historically underfunded HBCUs, “principally due to racism, whether institutional or otherwise.”

States have never fully honored their obligation under the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890 to treat historically Black land-grant institutions as they did predominantly white ones, Sheppard said, “principally because neither the legislatures or governors of those respective states deemed it important to do so.” Instead, he said, many states barely match federal funding for HBCUs, but they will spend multiple times more for flagship universities, where more of the students are white.

"Self-evidently, it's difficult to compete with primarily white institutions for agency R&D dollars when you don't have the money to develop and sustain the research infrastructure needed to compete or retain the faculty doing that very work."

-- David Sheppard

But even if funding were more equal, Sheppard, like Ross, said it would still take “a significant infusion” of federal funding to expand research at HBCUs.

“Self-evidently, it's difficult to compete with primarily white institutions for agency R&D dollars when you don't have the money to develop and sustain the research infrastructure needed to compete or retain the faculty doing that very work,” he said. “No disrespect to the Johns Hopkins and MITs of this country, but without a significant infusion of federal capital into the research enterprise at our institutions, we'll forever be relegated to second-class status because we can't keep pace.”

Gandara agreed that leveling the amount institutions have to spend to educate each of their students still wouldn’t bring about racial equity.

“If you acknowledge racialized inequities before a student gets to college, including in K-12 school finance, then funding parity between students of color and white students would be a starting point, but it would not be enough,” she said.

Still, increasing funding for colleges that bear a heavier load in educating students of color would be a start.

Implications of Disparities in Funding

The TICAS study noted that only 38 percent of community college students earn a credential within six years of enrollment. In comparison, 59 percent of students at four-year institutions graduate within that time. As of 2014, about 35 percent of students at HBCUs graduated within six years.

Certainly many moves by the federal government would help. Increasing research at HBCUs would make them less reliant on tuition, helping them continue to keep it low for students, Sheppard said. Particularly because of disparities in income, doubling the size of Pell Grants would mean Black students would not have to go into as much debt to pay for tuition and the other costs of going to college, he said.

But asked what she’d do with additional funding, Murphy, at the College of Southern Maryland, said, “The first thing I would do with more money is triple the advising staff to make sure every student has an adviser tracking them.”

She added, “We want to have people reaching out. ‘If you’re having trouble with math, let me set you up with something.’ We want to have someone say, ‘Wait a minute, you haven’t been in class. What’s going on here?’”

Janine Davidson, president of Metropolitan State University of Denver, a four-year institution, where 46 percent of the students are people of color and 80 percent work full- or part-time, also wished she could provide more help for students who struggle with attending college. Twenty-four percent of freshmen who first enrolled at the university in 2013 have since graduated.

“MSU Denver receives less than half the amount of funding per student compared to the average in Colorado,” she said. “This means that we can only afford a 500-to-one student-adviser ratio, with up to 800 to one for some of our advisers. With more funding, we would lower that to the best practice level of 150 to one.”

The university could do more if it had more counselors, said Will Simpkins, MSU Denver's vice president for student affairs. He'd like to have more who specialize in helping students overcome PTSD.

And things are difficult during the pandemic. The number of alerts distributed by faculty or staff members worried about students who are struggling or could be in danger doubled from 464 in the spring of 2019 to 910 this past spring.

The number of other cases sent to counselors about students struggling academically also doubled from 163 to 357 during that time, as classes moved online.

More funding, Davidson said, would also mean providing more wraparound services, like the City University of New York’s Accelerated Study in Associate Programs, which provides tuition and fee waivers, monthly transit passes, textbook stipends, tutoring, and intensive advising. Students who receive scholarships at MSU Denver receive that help, and between 80 percent and 95 percent graduate, compared to 68 percent of all students.

“So, we know what works. We just need to scale the effort,” Davidson said. “If we were better funded, this investment would have an enormous impact on student outcomes and, ultimately, on civil society and the economy in Colorado.”

But even the ASAP program is facing the ax.

Unique Challenges

The Association of Public & Land-grant Universities declined comment. But it has countered the criticism that four-year institutions get disproportionately more CARES Act funding, pointing out they have additional costs community colleges do not, including running residence halls. And four-year public universities are working to reduce racial disparities in attending college and graduating, such as through efforts like Powered by Publics, an initiative involving 130 institutions.

But community colleges say they have their own unique costs that more comprehensive colleges do not have to worry about as much.

Kenneth Smith has been a career coordinator and academic adviser at the College of Southern Maryland for a dozen years. One student, he remembered, was working to try to transfer to a university in South Dakota to play football. But he was living with his grandmother and his mother, who had health problems, and he was taking care of a younger sister.

“Life would get too heavy; he would disappear and miss too many classes,” he said. Smith did what he could, trying to help the student with time management. But he wishes he could do more to help students get jobs. And while he and other advisers will check in with students they see around campus, or in Smith’s case, at the gym, he’d like to do more of it.

But Smith is one of only two academic counselors for the 2,400 students who attend the college’s Leonardtown campus. Over all, the College of Southern Maryland employs 12 counselors for 6,900 students, or one for every 575 students -- about the same as MSU Denver. That's far too many to track to catch everyone who is having problems.

“I would love to grow the advising office,” Smith said. “There’s never quite enough advisers to service all of our students.”

Faculty and staff members are trying to pick up the slack, on top of their teaching, particularly as many struggle during the pandemic.

“Life would get too heavy; he would disappear and miss too many classes."

-- Kenneth Smith

College instructors these days are finding themselves teaching in places that feel out of the norm, like their living rooms. Or in the case of Joey Bowling, a math instructor at the College of Southern Maryland, one morning in June he found himself working in his car, parked by a playground in an apartment complex.

A couple of years ago, Bowling had noticed some students failing introductory math classes. Sometimes they’d try again. Sometimes they’d disappear.

“They were spinning their wheels and failing by just a little bit,” said Bowling, who teaches at a college where a third of the students are of color.

“We wanted to retain those students,” he said.

So he came up with the idea of a math boot camp, in which those who’d failed could get intensive instructions for two months. At the end, they’d take their final again. But when the university’s campus closed, like so many others around the country, the students needed computers and internet service to get a second chance on the final. One of Bowling’s students, who is Black, had neither.

“I thought I’d proctor the test, old-school,” said Bowling. And so around 10 a.m., the student sat at a picnic table at a playground in his apartment complex taking the test by pen and paper. Bowling sat nearby in his car.

The student, he said, got a B, and unlike many community college students who do not finish their degree, he is continuing on.

Miller, the professor who noticed the distraught student, said she and other faculty have been talking about how to get to know their students so they could better predict if they might drop out because of life’s struggles. They’re thinking, for instance, she said, about building in time for group games in class, like two truths and a lie.

“If you're able to really pay attention, you can see if someone is spending more or less time on responses. And if you notice a deviation, you can reach out. It takes tremendous time. If you need to teach five classes, your time is less,” said Stephanie McCaslin, the college’s associate dean of professional and technical studies and the chair of its math and engineering department.

Murphy said she sees her faculty go above and beyond to help students navigate their often complicated lives. She wishes she could pay them more and hire more.

“At other institutions, faculty work what’s known as a three-two schedule. They teach three classes one term and two the next term,” said. “Here they work a five-five. They’re people who we say pay a passion tax.”

The disparity in budgets between community colleges and four-year institutions comes in part from state and federal spending.

In the 2006-07 school year, according to TICAS, community colleges received $4,996 per student. Universities offering master’s degrees were less likely to enroll large percentages of students of color. But they received an average of $6,373 to educate each student, or more than $1,000 more per student than the more diverse community colleges.

Over the next decade, governments actually gave community colleges more funding than bigger universities, the study found.

Appropriations, mostly from states, which are the main entities funding community colleges, went up by 7 percent for community colleges, while they declined by 14 percent for colleges offering master's degrees and by 19 percent for those offering doctorates.

But the TICAS study said colleges offering advanced degrees, which tend to enroll wealthier students, could do what those serving larger shares of students from lower incomes can't do: raise tuition.

Universities offering master's degrees and doctorates raised tuition by about a half, while it only went up by a third at community colleges.

As a result, and with the gap so wide to begin with, community colleges didn't make up much ground despite the increase in government funding. Total revenue from both tuition and public funding went up by 16 percent, the same as for doctoral universities and only slightly more than the 13 percent more money master's-granting institutions had to spend. The gap was still in place.

In 2016-17, according to TICAS, community colleges still only had 61 percent of the revenue as those offering master's degrees and 37 percent of the money received by those offering doctoral degrees.

What Has to Change?

More funding equity would change how we think about higher education, said many experts, including Marybeth Gasman, distinguished professor of education at Rutgers University, New Brunswick.

“The biggest issue is that these institutions and their students are not being valued,” she said. “We as a society value highly selective research universities and highly selective liberal arts colleges. We have shown this over and over by what gets funded and what doesn’t. The recession amplified that issue. But ground was not first lost in the 2000s; the ground has always been uneven and full of potholes.”

Murphy agreed.

“Higher education funding is built on a 19th-century model, where a full-time student goes through a degree program in a prescribed amount of time. That doesn’t translate to what the 40 percent of undergraduates in the country need. Parity would mean our mission would be recognized as just as important as research universities. Our students aren’t lesser by any means,” she said.

“There is a racist, classist element here,” MSU Denver’s Davidson said. “Thirty, 40, 50 years ago, it was considered perfectly OK to underfund students of color or low-income students. We’ve been digging out of that hole for decades.”