You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Students’ biases about gender and other factors have been shown to skew how they evaluate their professors’ teaching. Growing wise to this, more and more universities are limiting the role that student evaluations of teaching, or SETs, play in high-stakes personnel decisions such as tenure and promotion.

But what about teaching assistants, who aren’t quite faculty, but whose instruction is still often rated by the students with whom they interact? Do the same biases show up in SETs of graduate student instructors as in SETs of professors?

Yes, according to a forthcoming study in the North American Colleges and Teachers of Agriculture Journal. Simple in design and sobering in its results, the study found that students in an online course who had the same TA gave that TA five times as many negative evaluations when they believed that she was a woman, as compared to when they thought she was a man.

Female students tended to give the putative female TA the worst scores of all, paralleling the U.S.-based findings of a major 2016 study on gender bias in teacher ratings.

Why does this all matter? Whereas negative evaluations of female professors may impact whether and how their careers progress, biased evaluations may discourage or prevent women from entering the teaching profession at all.

As they study says, “These SET discrepancies have the potential to affect the motivation of female graduate students to pursue careers in academia, and may impact hiring decisions, as SET scores are a frequently used tool for hiring committees in academia.”

Lead author Emily Khazan, a Ph.D. candidate in ecology at the University of Florida -- and the TA on whom the study is based -- said recently, “We already know that there is a leaky pipeline of women in STEM, and this study shows yet another factor in what influences retention in the field and in academia.”

Khazan continued, “Students’ perception of their teaching assistants clearly impacts their evaluations.” These evaluations, in turn, may have “downstream impacts on job prospects and also personal well-being.”

‘His’ and ‘Hers’

For their study, Khazan and her collaborators “deceitfully ‘assigned’” 136 students in a fall 2019 upper-level undergraduate course on natural resource ecology either a male or female TA, even though Khazan was really the TA for everyone. Students whose last names started with A through K got a “female” TA and rest got a “male” TA. The TA’s “gender” was based on made-up names and a photograph and short TA biography made available to students.

The course was taught online, asynchronously through the Canvas learning management system, with no face-to-face contact between Khazan and students. The course consisted of six learning modules of two to three weeks each. Assessments included exams, weekly quizzes, discussions, problem sets and a group project. The course’s instructor of record was a male associate professor who prerecorded lectures in a green-screen studio at Florida.

The professor referred to the female TA as “Ms.” in all class correspondence with last names A through K, and the male TA as “Mr.” in correspondence with the others, reinforcing the gender difference. To avoid what the study refers to as “fatigue-related grading bias,” Khazan logged in to both male and female TA accounts simultaneously and graded students in each group alternately.

Near the end of the course, at the same time the students completed a SET for their professor, students were offered 10 extra credit points for completing the evaluation or a separate extra credit assignment. The survey instrument contained demographic questions including respondents’ gender, age, classification, previous enrollment in online courses and assigned TA.

Specifically concerning the TA, a 14-item section asked students to rate, on a five-point scale, the assistant’s knowledge, teaching ability, approachability and professionalism. Out of the 136 students, 115 survey instruments were returned -- a very high response rate, though the majority of respondents (62 percent) were women. About half of respondents thought they had the female TA, and half had the male TA.

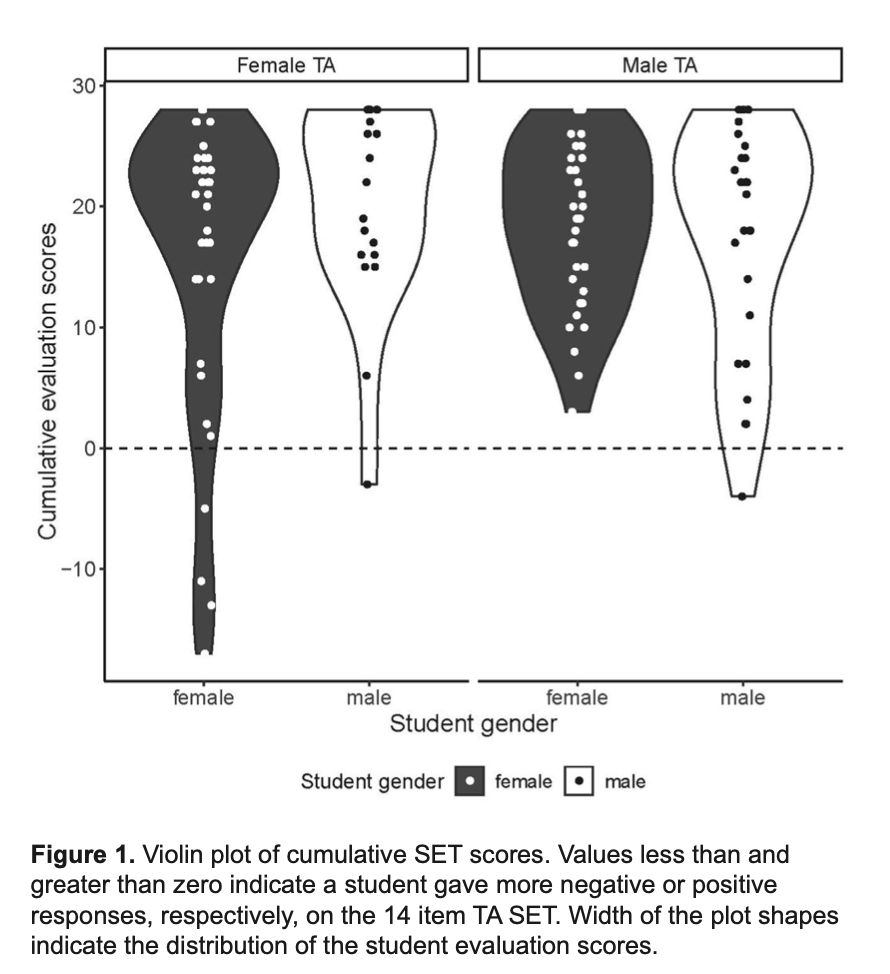

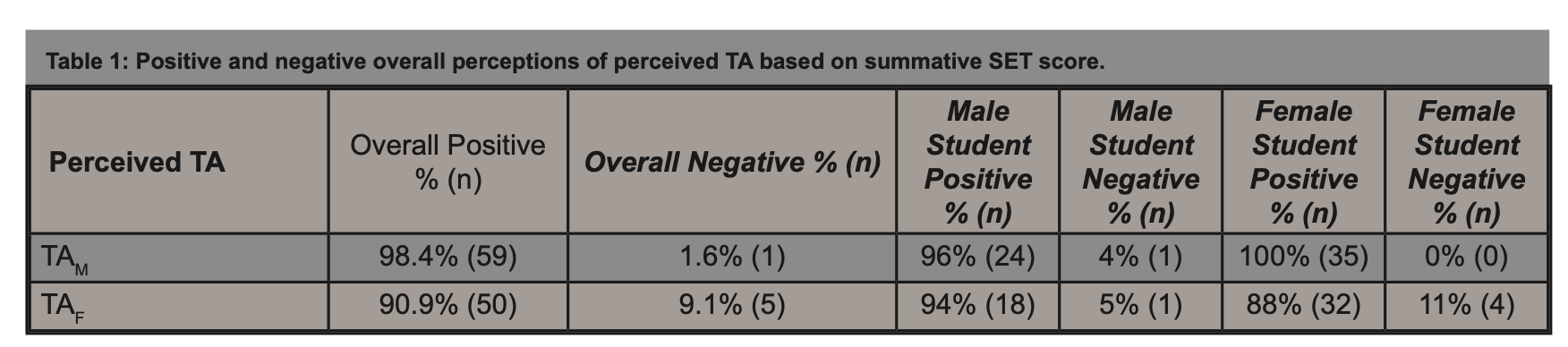

While the scores for both TAs didn’t differ significantly overall, the range of scores given to the female TA was greater. The male TA received 98 percent positive reviews, and the female received 91 percent positive reviews. Of the six negative perceptions reported, five of them were for the female TA.

Female students showed the greatest “discrepancy” in TA evaluations, according to the study, with 100 percent of female students assigned to the male TA giving him positive evaluations. By contrast, just 88 percent of female students assigned to the female TA gave her positive evaluations.

Male and female students rated the male TA similarly. Evaluations for the female TA were “less even and trended toward a statistically significant difference,” the study says.

Again, in actuality, the TA was the same person.

While the absence of a statistically significant difference between mean summative SET scores for the TAs is “encouraging,” the study says, the range of different scores for the female TA “demonstrates that perceived TA gender, even in the absence of in-person interactions, can impact student evaluations of TAs.”

Real-World Implications

Driving home the implications of their study -- and noting that ecology remains a male-dominated field -- the authors say this: “Had there been two TAs in the course who might eventually apply for similar faculty positions, the female may have been dissuaded from her pursuits as a result of the negative evaluations, even though her performance was equal to her counterpart.” Moreover, the study says, “selection committees do not consider statistical significance when comparing SET, as they only have the raw data available to them … Any observed difference can have real implications by influencing high-stakes decisions, including hiring, promotion or even appointment of graduate students as teaching assistants.”

Khazan and her colleagues recommend that future studies on SETs continue to investigate the effect of student raters’ gender, as well as how “context impacts bias.” Context here includes the gender diversity of a given field, and the method of course delivery. In an online, asynchronous course -- the kind COVID-19 is breeding more of -- “gender and expected traits and behaviors of gender roles may be less prevalent the more removed students are from the instructor, leaving less opportunity for unconscious gender bias in SET.”

In other words, the effects of this study might have been larger -- that is, worse for women -- in an in-person course.

Finally, the study encourages continued research on TAs and experiences with student ratings.

Graduate students navigate a “particularly challenging time balancing multiple responsibilities and weighing significant life choices,” Khazan and her colleagues wrote. “Those challenges are enhanced in STEM in many ways for women, people in underrepresented minority groups, and particularly for women of color or other underrepresented groups. It is imperative that we support our graduate assistants and mentor them through receiving, interpreting and applying feedback from SET.”

Khazan reiterated that SET scores don’t affect her grades, but that they may impact TAs' course assignments. More personally, she said, “SETs can be personally offensive and upsetting.”

Professors who lead courses may be unaware of the “degree of gender bias in SETs and often take the student evaluations seriously,” she said. Khazan added that she’s been “reprimanded by professors in the past for negative student evaluations” and told to “change the personality that I bring to the classroom and present to students.”

Laura L. Greenhaw, an assistant professor of agricultural leadership development at Florida and a co-author on the study, said that while SETs may not be the only metric used to evaluate a graduate student’s teaching performance, they can be “an influential one, especially if that student is the primary instructor for the course.”

As an adviser, Greenhaw said she’d be “missing a fundamental teaching opportunity if I did not talk with my graduate students about their teaching.” Beyond that, she said, graduate students may compete for awards and recognition based in large part on their teaching records -- not to mention competition for faculty jobs.

Negative evaluations, “even if just a few, can have a real impact on individual opportunities,” Greenhaw said. So when SETs don’t “accurately reflect teaching quality and effectiveness,” they’re “detrimental not just to the applicant, but to our profession as a whole.”