You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

New projections show more high school graduates across the country through the mid-2020s before a downward trend takes over.

Ben Hasty/MediaNews Group/Reading Eagle via Getty Images

Increased public high school completion rates, especially among students of color, are helping to propel the nation’s graduating classes to larger-than-anticipated sizes -- but they aren’t projected to prevent a steady contraction looming after the middle of the 2020s.

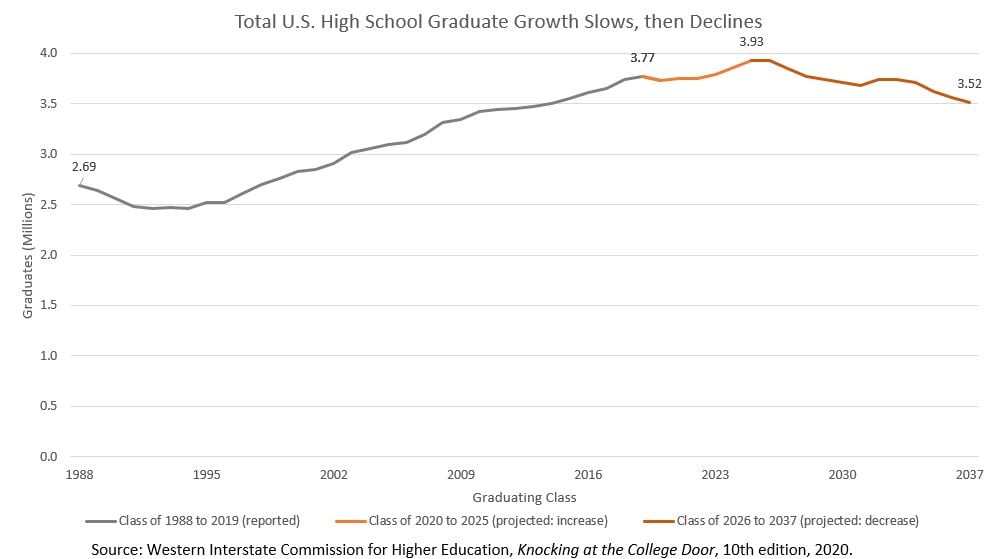

High school graduates are on track to peak in number across the country at 3.93 million with the Class of 2025, according to projections released Tuesday by the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education. That’s about 4 percent above the 3.77 million high school graduates in the Class of 2019. After 2025, the projections show graduating classes declining moderately in size over a dozen years due largely to the so-called birth dearth that dates to families having fewer children amid the economic disruptions of the Great Recession.

Graduating classes are expected to diversity significantly in the coming years, continuing a trend already under way in which students of color make up larger shares of diploma recipients than they have in the past as white students decline relatively in number. Also changing is where numbers of graduates will be located, as regions and states experience differing local trends in coming years.

Broadly speaking, projections anticipate the Northeast and Midwest posting largely flat numbers through 2025 and then declining afterward. The South is projected to experience growth in high school graduates until 2026 and then dip somewhat to levels that are still mostly higher than those of recently observed years. In the Western region, some small-population states are expected to increase high school graduate production, only to have their numbers offset by declining graduate totals in the population center of California after 2024.

The Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, or WICHE, releases projections about coming numbers of high school graduates every four years or so. Policy makers and higher education officials closely watch the organization’s projections because they offer insight into future pools of traditional-age students who will enter college and the workforce. Those factors will in turn affect everything from university budgets to state financial aid programs to job markets.

In its previous set of projections, issued in 2016, WICHE predicted relative stagnation in the number of high school graduates nationally. At the time, the group expected between 3.4 million and 3.5 million high school graduates every year between 2013 and 2023, followed by a few years of growth. Graduates were expected to peak at 3.56 million in 2026. The projections prompted significant worry among colleges leaders, stoking predictions of colleges closing or merging.

The new projections offer a slightly more optimistic near-term picture but don't change the fundamental situation. The new projections and recorded numbers of graduates are coming in about 10 percent higher than they would have under the projections from 2016. The difference is due in large part to improvements in high school graduation rates in recent years, especially for students of color. About 75,000 more Hispanic public high school graduates were counted in the Class of 2019 than were expected under the projections issued in 2016. Graduates reported as multiracial also increased markedly.

Private high school enrollments contributed to the higher-than-expected number of graduates as well. Previously, patterns of private school enrollment showed contraction. But the number of private high school graduates is now expected to rise by as much as 13 percent between the Classes of 2017 and 2025.

Those factors are enough to drive short-term growth in high school graduate production that previously wasn’t expected. It’s an important development because education systems have grown used to steadily growing high school graduating classes nationwide -- growth has been reported for decades. But within five years, the factors pushing toward larger graduating class sizes aren’t expected to be enough to counteract the effects of birth rates that plunged as the Great Recession took hold.

“There simply aren’t enough high school students 18 years later to continue that trend of growth,” Patrick Lane, vice president of policy, analysis and research at WICHE, said during a conference call to discuss the projections.

In 2037, the U.S. high school graduating class is projected to total 3.52 million students -- roughly the same size as it was in 2014.

WICHE calculates its figures by projecting recent school attendance and graduation patterns onto cohorts of children as they’re born and rise through the grades. That method might be reliable in normal times, when huge shifts in the educational landscape are rare.

This year, though, it comes with an asterisk. The COVID-19 pandemic is having a significant impact on schooling.

“COVID-19 impacts could have the potential to change the numbers projected if the trends in graduation rates were to be altered,” said Peace Bransberger, senior research analyst at WICHE.

Some research has shown that high school graduation rates increased in 2020, possibly because the poor economy prompted some students to stay in class instead of dropping out to look for a job. But any number of other pandemic-related factors could pull graduation rates up or down for years into the future. For instance, some data suggest the pandemic has had a greater effect on middle school students than on other students, potentially shaking the college admissions market in 2025, when today’s middle school students will be graduating.

“We certainly expect that the pandemic will have a significant impact on students and potentially an outsized impact on low-income students and students of color,” Lane said. “But it will take several years for those impacts to show up in the data we collect.”

With all of the disruptions currently playing out, WICHE plans on providing new information on state-level trends as new data from the 2019-20 to 2021-22 school years become available. It might adjust its latest projections as appropriate.

Regardless, the new projections support a high-level conclusion unchanged by the pandemic, according to a report WICHE released detailing the projections.

“Improvements in high school graduation rates are leading to more high school graduates than previously projected and offsetting some -- but definitely not all -- of the expected national declines beginning in 2026,” it said. “High school graduating classes will continue to become more diverse, led by growing proportions of Hispanic and multiracial students in particular.”

It calls for education systems to address systemic inequities creating disparate educational outcomes by race and ethnicity. The pandemic only exacerbates such a focus, Lane said.

“The challenge now is laid bare by the pandemic,” he said. “We really need to protect the gains that we’ve made and continue to redouble our efforts to address the systemic inequities that have been hampering many students and continue to make improvements rather than lose ground.”

Projections by Race and Ethnicity

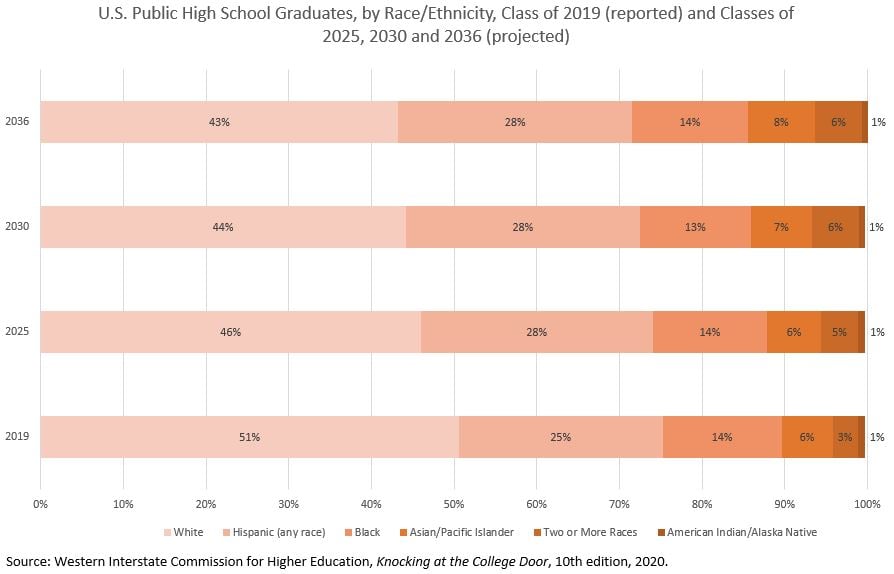

Projected increases in public high school graduates’ diversity are fueled in large part by rising numbers of Hispanic graduates and graduates of two or more races.

In 2019, for example, 25 percent of graduates were reported as Hispanic of any race, and 3 percent were reported as two or more races. By 2025, 28 percent of high school graduates are expected to be Hispanic and 5 percent will be reported as two or more races. In 2036, the graduating class is still expected to be 28 percent Hispanic, but those identifying as two or more races are projected to have doubled to 6 percent of the class.

Also projected to rise is the percentage of high school graduates who are Asian or Pacific Islander. The Class of 2019 was 6 percent Asian and Pacific Islander. By 2030, that’s expected to rise to 7 percent. By 2036, it’s expected to grow to 8 percent.

Holding steady throughout the projections is the percentage of expected graduates who are Black and the percentage who are American Indian or Alaska Native. The percentage of graduates who are Black is anticipated at about 14 percent throughout the period. The percentage who are American Indian or Alaska Native is expected at about 1 percent.

Meanwhile, white graduates are projected to fall from 51 percent of the Class of 2019 to 43 percent of the Class of 2036.

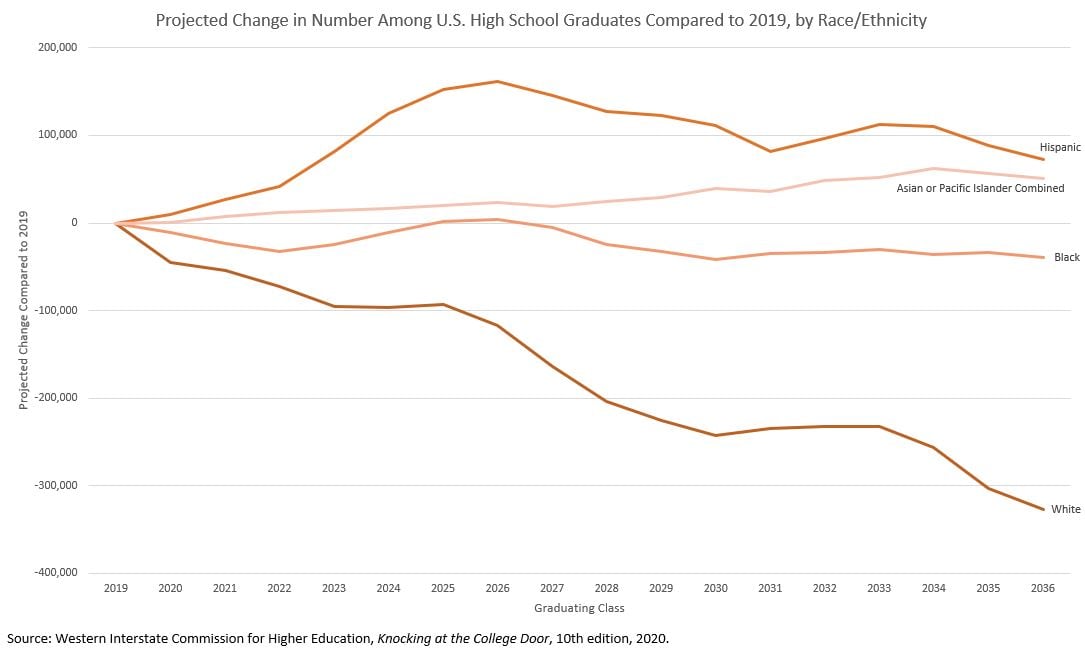

Changes in the demographic proportions of each class don’t capture the way the actual number of high school graduates is expected to change. Even though Black high school graduates are expected to hold relatively steady as a percentage of all high school graduates, there are projected to be fewer Black high school graduates in the future than today, for example. In 2036, projections show almost 39,000 fewer Black high school graduates than there were in 2019. White high school graduates will also shrink considerably, down by almost 330,000 in 2036 compared to 2019 levels.

Conversely, Hispanic high school graduates are projected to number almost 73,000 more in 2036 than they did in 2019. That’s would actually be down from 2026, when Hispanic high school graduates are projected to number more than 162,000 above 2019 levels. Projections show about 50,500 more Asian and Pacific Islander high school graduates in 2036 than there were in 2019.

WICHE isn’t able to estimate the race and ethnicity of private high school students. The federal government has estimated nearly seven in 10 private elementary and secondary school students were white in the fall of 2017.

By Region

The South outpaces the country’s other four regions in its projections for future high school graduates. In 2019, the region recorded 1.43 million high school graduates. It’s on track to peak at 1.54 million in 2026, then decline to 1.42 million in 2037. Notably, Texas and Florida are projected to post larger high school graduating classes in almost every year compared to their 2019 levels -- even after 2025.

The West produced just under 910,000 high school graduates in 2019. Projections show the region hitting 962,000 graduates in 2024 before sliding to 833,000 in 2037. About half of high school diploma production in the region is driven by California, which accounted for almost 485,000 graduates in 2019, is expected to peak at about 507,000 in 2024 and is in line to see just 411,000 in 2037.

In the Midwest, high school graduates totaled just under 786,000 in 2019. They’re expected to peak at 791,000 in 2025 and decline to about 693,000 in 2037.

Just over 644,000 high school graduates were reported in the Northeast in 2019. The region is on pace to peak at just under 651,000 in 2025 and tail off to about 571,000 in 2037.

Ten states generate more than half of all high school graduates in the country. Most of them are projected to post stable numbers of graduates over the next five years. Afterward, all but one, Florida, are expected to see their graduating classes shrink between 2025 and 2037.

Just two, Florida and Texas, are expected to have larger high school graduating classes in 2037 than they did in 2019.

Private School Enrollment and the Post-COVID Future

Looking forward, rising enrollment in private high schools could soften the blow of public high school declines. Even when projections show public high school graduates dropping in number in the years after 2025, WICHE is projecting the number of private high school graduates continuing to increase. The organization expects 9 percent more private high school graduates in the Class of 2030 than in the Class of 2017.

Enrollment pattern estimates show changes in the distribution of students at schools categorized as Catholic, other religious schools or nonsectarian.

“Whereas previous trends were dominated by the decreasing Catholic school portion, the projections for private school graduates from 2020 to 2037 are strongly influenced by recent rapid enrollment increases for non-Catholic religious private schools and nonsectarian schools,” the report on the projections said.

Possible contributing factors include the economic recovery that followed the Great Recession and policy changes. But it’s too early to draw conclusions based on the available data.

More recently than would show up in the WICHE data, it’s also possible some families turned to private schools that were holding in-person classes this year after they found that their local public schools did not reopen classrooms amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

“What we don’t know is how that is going to, in the long term, affect some of those enrollments,” said Demarée Michelau, president of WICHE.