You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

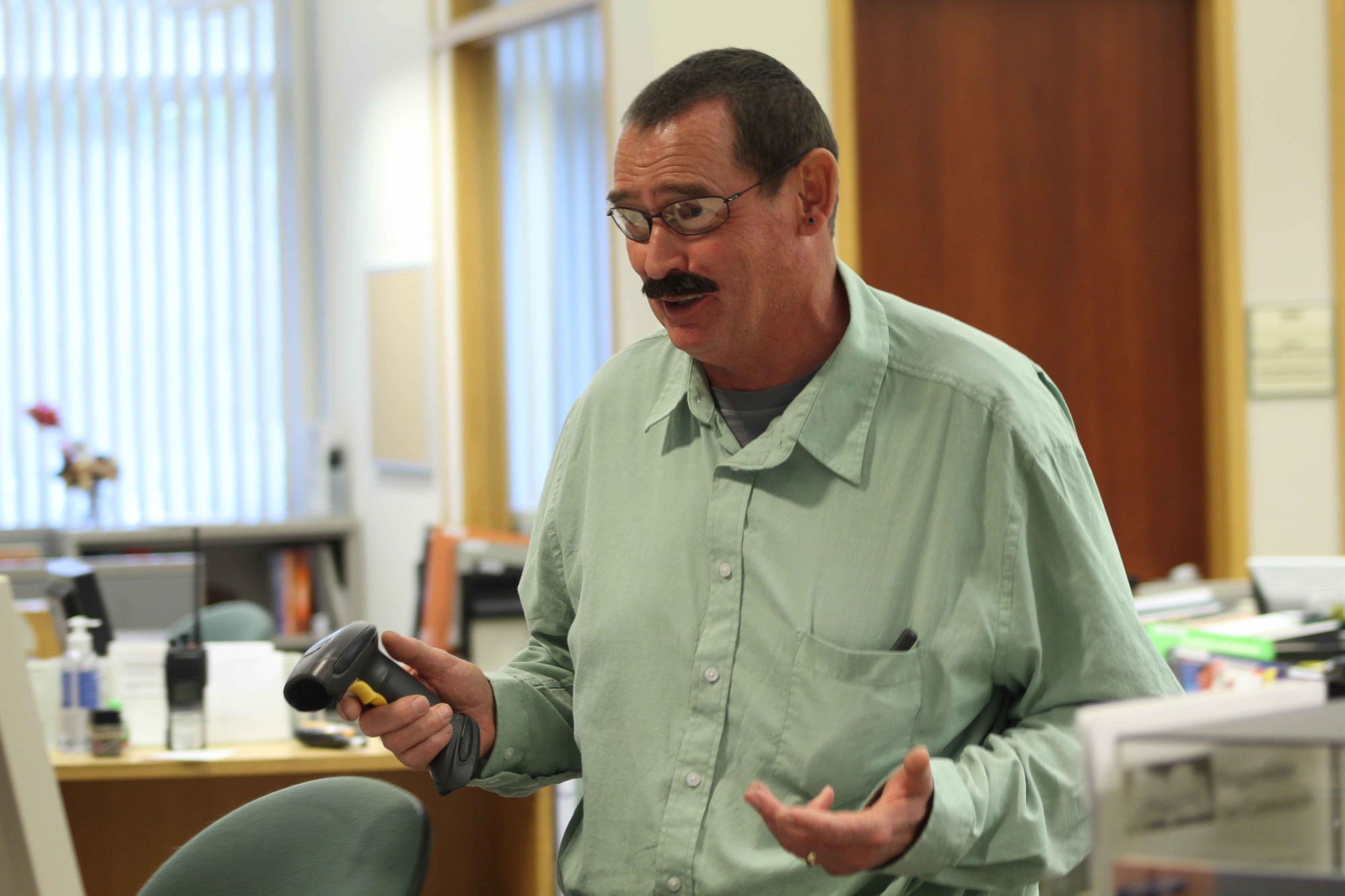

California State University chancellor Timothy P. White delivered his first State of the CSU address in Long Beach in 2014. White is now retiring after extending his chancellorship amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Jeff Gritchen/Digital First Media/Orange County Register via Getty Images

Timothy White, the chancellor of the California State University system, broke with most of his peers in May by announcing that the sprawling 23-campus system would be planning to hold most courses online in the fall.

At the time, many other college and university leaders were broadcasting bullish messages about in-person instruction amid the pandemic. Fears ran high that students wouldn’t enroll for the fall if they knew classes would be primarily online and that the quality of virtual instruction would lag that in classrooms. Lost revenue from closed dormitories and other auxiliary services threatened to shatter carefully crafted institutional budgets across the country.

When making his decision, White considered the different elements of the Cal State system, which counts the nearly 500,000 people it educates annually as making up one of the most diverse student bodies in the country. What were students’ and employees’ perspectives? How could the 23-campus system hold true to its mission of helping students progress toward degrees in an environment of such uncertainty?

His answer -- defaulting to online instruction for the fall but allowing exceptions for compelling cases like clinical or laboratory classes -- provided at least some certainty. It also had the benefit of being easier to reverse if public health conditions had changed.

“If I was wrong, I told myself, I can live with that mistake,” White said. “I’m not going to hide my head.”

The chancellor’s office has gone on to publicize plans for two more upcoming terms. Spring 2021 coursework will continue to be mostly virtual, White said in September. For fall 2021, planning is under way for a return to mostly in-person courses, he announced this month.

White wasn’t originally supposed to be in a position to make those calls. Last fall, he announced plans to retire at the end of June 2020. A search for his successor started.

But White had left some wiggle room, telling trustees he’d leave no earlier than the beginning of July and no later than the end of December. When the pandemic was declared in March, he said he’d stay on the job into the fall.

The result was an experienced leader at the helm who could guide the system through a crisis without fear of spending too much long-term political capital, said Lillian Kimbell, the system’s board chair.

“He had nothing to gain, in a way, or nothing to lose,” she said. “I think the stability that he’s provided and the direction have been invaluable.”

Now, White, 71, is drawing to a close what will turn out to be an eight-year run in office. What, exactly that means for Cal State has yet to be written. Joseph Castro, president of Cal State’s university in Fresno, will take over the chancellorship at the beginning of January. Castro served his entire seven-year presidency in Fresno with White as system chancellor and has said he wants to build on his predecessor’s tenure. Both leaders acknowledged that the system will have to evolve as the pandemic gives way to a new world.

In some ways, White found himself in a similar situation when he stepped in to lead a recession-ravaged Cal State system at the end of 2012. He took some of his predecessor’s key policies and built on them while also setting out in different directions. Hailed as a breath of fresh air when he first arrived in the chancellorship, his administration has pushed popular policies focused on degree completion. It has also backed controversial ideas, like remedial education requirement reform, and unpopular ones, like additional quantitative reasoning requirements for high school students applying to an institution in the system.

Through the ups and downs, White has earned the respect of his peers across higher education and steered the Cal State system as it strengthened its financial position and boosted its degree production. Speaking about the system and his upcoming retirement during interviews at several points over the last year, White expressed pride in his work and frequently drew connections to his life and the ways Cal State affects the state and its students. Cal State conferred almost one million degrees during his tenure, he said.

“People like to be associated with something that matters,” White said. “Telling the stories of our students, who come from remarkable headwinds and backgrounds -- some come from privilege, but a lot come from abject poverty -- those stories and seeing what they’re doing now are just really, really remarkable.”

“I like being the storyteller,” he said.

‘I Didn’t Come in Saying I Need to Change a Culture’

The Cal State system is the middle child in the California Master Plan for Higher Education, a 1960 framework differentiating between public colleges and universities in the state.

The plan designated the University of California system to hold the state’s primary research enterprises within its widely known institutions offering undergraduate, graduate and doctoral programs. The California Community Colleges were set up to offer two-year programs and vocational instruction, plus the ability to transfer to four-year institutions. In between is Cal State, tasked first with undergraduate education, including teacher education, as well as graduate programs. The original plan's boundaries have blurred in some cases over the years. Cal State system leaders say they sometimes must remind others that their institutions perform their fair share of research.

Generally, the Cal State system has enjoyed long-tenured leaders. When White started in 2012, his predecessor, Charles B. Reed, had been in the position since 1998.

Reed retired with a mixed legacy that in part reflects how hard it can be to lead the system. When he retired in 2012 at the age of 71, the Los Angeles Times wrote that Reed “became a symbol of the problems and promise of the massive public higher education system.” It credited him for efforts to increase underserved student enrollment and to lead the system through massive state budget cuts of almost $1 billion from 2008 to 2012. But Reed also drew criticism for increasing charges to students -- student fees rose 167 percent over a decade -- and for executive pay increases.

Cal State enrollment had peaked in 2008 at 440,000 students before dipping to 425,000 in 2012. Campuses were turning away eligible students and cutting services as the Great Recession reverberated through budgets.

The Times also wrote that Reed’s leadership style was “seen as often blunt and bullheaded.” A lawmaker told the Times that if Reed had a fault, “it is that he was more concerned with doing the right thing than getting the public relations right.”

The then-president of the union representing faculty members labeled Reed as “leading with his chin, ready for some kind of slug fest” and said the system moved toward something resembling a privatized model during the chancellor’s tenure. Reed responded in kind, saying the union leaders didn’t represent their rank and file and instead wanted to fight and demonize him.

White largely avoids talking about the system as it was before he arrived. He was quick to point out that he never experienced the culture there, at least since he was a student himself decades ago, at Fresno State and Cal State, East Bay.

But when he was named chancellor, White started on a sharply different note than his predecessor. He asked for a 10 percent pay cut compared to Reed, who earned $421,500 in salary. White was eventually tagged to start out earning $380,000 with a $30,000 supplement from the Cal State foundation.

The move caught the attention of the faculty union.

“We thought that initial decision demonstrated goodwill and responsible leadership during a historic recession, during which most faculty and staff were suffering,” said Charles Toombs, the current president of the union, the California Faculty Association.

White laid out two goals for himself: educate California and give back to the system, which helped launch his own career.

“That was it,” White said. “If that meant changing a culture, great. But I didn’t come in saying I need to change a culture. I just need to be me, and I need to get people smarter than me to make the ideas even better.”

White had the sense the system was picturing itself “as Rodney Dangerfield -- woe is us.” His response was to stop talking about what the system didn’t have and focus more on what it did -- and does -- have. It enrolls the better part of half a million students from all walks of life who go on to work in a state that, if it were its own country, would have the world’s fifth-largest economy.

White has described himself as a “windshield guy, not a rearview-mirror kind of guy.” When he was an administrator at Oregon State, he symbolically broke a rearview mirror because 30- and 40-year university employees were coming into his office to tell him how things ran back in the day.

He kept the shattered mirror in his corner office at Cal State.

“The things in the past aren’t as important as you think,” White said. “The sand has shifted. It’s a different set of needs and expectations for our students and for our communities.”

Yet White doesn’t endorse disregarding the past. Stand on its shoulders, he said.

He’s often drawn on his own past when leading.

The Path to Chancellor

White was born in Buenos Aires in 1949. When he was 5, his father decided to leave the country for the United States. The family went first to Canada, where they had difficulty finding a sponsor in their first choice of a new home, New York. Eventually, a sponsor surfaced in the Bay Area, and the family moved there.

White didn’t know for decades why the family left Argentina. At some point, when White was in his 30s or 40s, he remembers his father telling him. His father referenced the controversial leader Juan Perón and tumultuous times in Argentina when it seemed as if politicians threatened the facts being taught in school.

“He said, ‘Tim, they were starting to change the textbooks, and I just didn’t want …’” White trailed off. He described his father as “not an educated guy” but one who went to high school and valued education.

White called himself “a screwball kid in high school, good enough to be in the top 100 percent of my class.” He went on to attend an institution at each level established by California’s Master Plan: Diablo Valley Community College, where he was involved in swimming and water polo; Fresno State; Cal State, East Bay; and the University of California, Berkeley. He carved out an academic background in physiology, kinesiology and human biodynamics.

He rose through academia, eventually becoming dean of the College of Health and Human Performance at Oregon State in 1996. Then in 2000, he was named provost and executive vice president at Oregon State.

After he landed the job, his parents decided to come see him.

On the way, their car went off the road and hit a tree. White's father died instantly. His mother was critically injured and went through months of rehabilitation, then died a few years later.

White thinks of the day as claiming both of his parents’ lives, describing his mother as “simply done after Dad was killed.”

Telling the story in January in the chancellor’s office in Long Beach, White paused.

“They were driving up to see the corner office,” White said. “And, 30 miles from campus, hit a tree. So they never saw the corner office.”

Then White reached for the connection to today’s students. Whether their families emigrated to the United States from Mexico, Korea or Nicaragua or whether they grew up in Hemet in California’s San Jacinto Valley, their families sacrificed for them, he said.

“I know the facts are different, but the stories are the same for hundreds of thousands of Cal State kids,” White said. “It’s been an intrinsic piece of who I am.”

White went on to become interim president at Oregon State, taking the role after Paul Risser left for a position in Oklahoma. Taking that role meant turning down an opportunity for White. He couldn’t be considered for the presidency on a permanent basis if he held the title as an interim. He was given the option of remaining as provost and working with another interim, though.

Oregon’s Legislature sets a budget every two years. The biennial session was bearing down at the time, White said. He knew the university would be affected by what happened.

“Nobody on that campus knew Oregon State and its needs and its stories better than I,” White said. “Because of that legislative session coming, for four months of intense activity in Salem that creates your budget for the next 24 months, I decided I would be the interim president, and I knew the minute I made that decision that I would be leaving Oregon State.”

Other opportunities arrived.

In 2004, White was named the University of Idaho’s next president. He stated priorities for the university that would sound up-to-date at many institutions today. They included forging partnerships, being more student-centered and building diversity.

That May, before he started at Idaho, he suffered a heart attack. He felt a pain between his shoulder blades, he later told The Spokesman-Review. His wife, Karen, searched the house for aspirin and packed him into the car, bound for the hospital. He had a quintuple bypass.

The experience gave White perspective. He had three children from a previous marriage. His wife had recently given birth to a son.

“I confronted a flatline EKG as I laid there with my 2-month-old son held in my wife’s arms,” White said. “I think, with experience, I’m comfortable in my own skin.”

White recovered, served for four years as university president in Idaho and then took the presidency at the University of California, Riverside. There, he rose to unexpected prominence with an appearance on the CBS television show Undercover Boss.

White recovered, served for four years as university president in Idaho and then took the presidency at the University of California, Riverside. There, he rose to unexpected prominence with an appearance on the CBS television show Undercover Boss.

The show has leaders donning disguises to see their organizations through the eyes of others. White appeared on the show in 2012. He cut his hair and sported a fake mustache, earring and false teeth. He posed as a professor, assistant track and field coach, campus tour guide, and library staff member.

Cameras showed White struggling with menial labor such as shelving books or carrying track equipment. As the episode drew to a close, he revealed himself as chancellor to the people who had unknowingly worked with him, handing out scholarships along the way and announcing that the track would be replaced. There were also tearful moments, like when he and another student cried after sharing stories of lost loved ones.

Seeing himself on the screen was an interesting experience, White said. He doesn’t see himself as the staid title of chancellor. Still, he thought his love for the educational mission came through clearly.

“It was interesting for me to see how they characterized me, because I’m just Tim,” White said. “It made me feel proud about this notion of genuinely authentic care about what I’m doing.”

When White appeared on Undercover Boss, higher education wasn’t drawing much positive press. Stories at the time tended to be about tuition going up or students unable to find space in classes they needed to graduate, White said.

In retrospect, he’s glad he appeared on the show. But it was a risk. His team at Riverside didn’t have editorial control, so any issues that were problematic could have been played up onscreen.

“Some faculty thought it was below the dignity of what a chancellor should do,” White said. “After they saw the show, all of the negative stuff went away. Because it painted a picture of sort of authenticity, engaging with students and with faculty and that wonderful learning environment that a university is, and portraying real-life stories that these students had developed or had experienced that aligned in a rough way with my life story.”

People remembered him from the show years later.

“I have met people on the Metro system in Washington, D.C., who came up to me on a Saturday when I was there with my family in tennis shoes and a baseball hat saying, ‘Are you the chancellor?’” White said.

Shortly after White’s episode of Undercover Boss aired, he was named the next chancellor of the Cal State system, or the CSU. His title wouldn’t be changing -- in the University of California system, campus presidents are chancellors, and the system leader is the president, while the reverse is true in the CSU.

No matter the title, it was a major step, if an unorthodox one.

Leading the CSU

Mark Yudof was president of the University of California system when White applied to be CSU chancellor.

“When he came to my office to tell me he put his name in for Cal State, I thought he was nuttier than most academic administrators,” Yudof said. “It’s an extremely difficult job. There are so many campuses, so many constituencies.”

The Cal State system had started trying to increase graduation rates for students in 2009 with a six-year graduation initiative. After he took over, White stood on the shoulders of that idea, championing it.

In 2015, the system said six-year graduation rates for first-year students had surpassed goals set under the original Graduation Initiative. At the time, 57 percent of first-year students were earning degrees within six years. The system reported its four-year graduation rate as 19 percent for the cohort of students entering college in 2011.

The system went on to set new goals under the banner of Graduation Initiative 2025. It’s striving for first-time students to post a four-year graduation rate of 40 percent and a six-year graduation rate of 70 percent. For transfer students, the goal is a 45 percent two-year graduation rate and an 85 percent four-year rate.

Rates have improved, but work remains to be done to meet the goals. The four-year graduation rate for first-time students remains furthest below its goal, coming in at 31 percent as of 2020.

Advocates also worry that the system has focused on the top-line graduation improvements even as rates for underrepresented students lag.

“Their own data shows graduation rates are up, and they’re up significantly, so that’s really good news,” said Michele Siqueiros, president of the Campaign for College Opportunity. “The chancellor’s office has not been as forthcoming at disseminating data around the racial gaps that continue to persist. In fact, the data we see shows those gaps are not closing. The gaps are not improving for Black students, Latinx students, in ways we would have hoped to have seen at this point. I think that continues to be an important priority and area of focus.”

More controversial was a proposal from the chancellor’s office to require incoming students to take an additional year of quantitative reasoning coursework in high school. The proposal would cover students starting as freshmen in several years.

The idea was hotly debated before White delayed a vote scheduled for early this year. It’s now under study.

Critics argued in part that the requirement was onerous for students attending high schools that don’t have the resources to offer such classes in large numbers. Disparate access to those courses breaks along the lines of race and ethnicity, they say. Further, they didn’t think the chancellor’s office met the burden of proof when arguing that the requirement was needed, and they worried it would amount to a rationing system to weed out students in a system where demand for some institutions can outstrip capacity.

White positioned the idea as a boon to students. The additional quantitative reasoning coursework would boost their college prospects and open up new majors and lucrative careers, he reasoned. The policy would do no harm but would do good for thousands of students, he said in January, shortly before the idea was postponed. He realized that most of the pushback against the policy was coming from Californians who worried the changes would threaten students' access to a Cal State education.

“I respect people who have a different opinion,” he said.

White’s administration has also drawn praise from those who are focused on access. Siqueiros described as a major achievement executive action that essentially retired the use of assessment exams for English and math placement while also eliminating no-credit remedial education courses.

“It follows the very robust research nationally about the problematic placement tests and their disparate impact on, especially, first-generation communities of color,” she said. “It is a recognition that you can find ways to do a better job of serving students, and their own research has indicated incredible success in terms of that policy.”

Siqueiros also noted that White has demonstrated a commitment to hiring diverse campus presidents, particularly by gender. Twelve of the system’s 23 campuses are led by women.

The system has worked hard to broaden applicant pools, focusing on its search processes. It has held open campus forums early to gather feedback about an open presidency. But it has not disclosed the names of applicants during the searches themselves.

Doing so arguably shields applicants who might feel vulnerable in their current jobs. Search experts have said potential candidates who are women or people of color are often concerned about backlash from their current campuses if they publicly apply for a presidency elsewhere but are not selected. Not disclosing applicant names is designed to give candidates confidence that they won’t be punished in their current jobs for throwing their hats into the ring elsewhere.

If the system works, it should create a more diverse group of campus presidents over time. At the very least, the hope is that a diverse group of sitting deans, provosts and presidents will apply for positions, receive feedback on their applications and safely return to their old jobs if they aren’t hired -- with important experience to help them the next time they apply for a presidency.

“It creates a safe place for people to come, to both learn about the place beyond what you see written and to have a chance to be reviewed and interviewed in a safe environment,” White said of the system’s search process in 2016. “From that, we’re getting diversity of gender and diversity of race and ethnicity in ways that we have not been able to do in the past.”

Closed searches are often criticized by faculty members who want more information on hiring campus executives and more say over which candidates are chosen.

White’s relationship with faculty has at times been rocky. The remedial education reforms were not universally well received among faculty ranks. A long battle unfolded over implementing systemwide ethnic studies requirements from the chancellor’s office. It continues today, even after California legislators passed a new law on the matter. The faculty union has also advocated for more tenure-track faculty members.

In 2016, negotiations with the California Faculty Association grew tense. Compensation was a sticking point, and a strike was only averted at the last minute when system leaders agreed to a pay increase.

The next year, trustees approved salary increases for executives and a tuition increase. It was the first tuition increase in six years.

Toombs, the president of the California Faculty Association, said the 2016 negotiations could have been handled better.

“He took CSU to the brink of a historic strike before finally agreeing to do the right thing for the faculty,” Toombs said. “We certainly think that situation could have been handled more collaboratively.”

Looking back on that time, White wishes some things had gone differently. It was a challenge to not become frustrated as bargaining dragged on and interruptions mounted, he acknowledged.

He still says the system has to live within its means.

“One of the things that comes with experience is not letting the annoyance get in the way of doing the right thing,” White said. “Sometimes you’ve just got to take a deep breath to get there. But I don’t think I’ve ever really screwed that up.”

‘A Very Understated Way’

Those who’ve worked with White in different professional capacities recall him often not seeming to need that deep breath. Harold Hewitt served with White on an accreditation commission several years ago.

“He had this way of getting people to a uniform position without bullying, without being forceful,” said Hewitt, who is executive vice president and chief operating officer at Chapman University, which is also located in California. “He remained calm. He provided brilliant ideas in a very understated way.”

White has often spoken to different presidents in the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, said the organization’s president, Peter McPherson.

“I think probably what he’ll be remembered for best is his work on degree completion,” McPherson said. “Access and degree completion.”

White understood listening, messaging and communicating, others said.

Jamienne Studley, a former official in the Obama administration’s Department of Education, remembers meeting White and discussing the College Scorecard, a tool intended to provide the public with easy access to key information about different institutions. The idea of holding a series of meetings around the country to talk about the Scorecard was circulating.

“We mentioned we were interested in doing these open meetings, and he instantly understood just what we needed,” Studley said. “He said, ‘I’m sure any of the CSUs would be happy to host a meeting around a subject as important to you and student success as that. For example, Dominguez Hills is the perfect location, convenient to a major airport, and I’m sure would be a welcoming spot for you.’”

Studley, who is now president of the Western Association of Schools and Colleges Senior College and University Commission, said White was right about the location. They held the meeting at Dominguez Hills.

She also thinks White is uniquely confident in his own skin. She shared a news clip of White visiting Sacramento State, dancing on the sidewalk.

“Who would do a silly dance like that knowing there’s a camera running?” she asked. “He’s incredibly real.”

Administrators and advocates alike credit White for successes winning public funding. Janet Napolitano was president of the University of California system for most of White’s tenure at the CSU. They coordinated regularly, holding monthly calls. They advocated together in Sacramento.

“He was easy to work with,” Napolitano said. “He appears low-key, but he knows exactly what he’s doing and how he wants to get there.”

White is much the same in person as he appears in a public meeting or on television. His demeanor is typically calm and thoughtful. He will occasionally slip colorful language that other administrators might shy away from into an on-the-record answer. Consider the following comment on his decision to default to virtual classes this fall.

“Some students who, early on, were so pissed off we were taking away the college experience have now raised their hands and said, it allowed me to plan, and I had a fantastic semester,” he said.

He will not shy away from forcefully defending himself when he feels it necessary.

Last year, a state audit found that the chancellor’s office gathered a “discretionary surplus” totaling more than $1.5 billion, largely from excess tuition revenue. Such reserves can be criticized as hoarding, particularly if an institution building its reserves does so at the same time it raises tuition or gathers more money in state funding. Cal State had raised tuition over the decade covered by the audit, and the news drew criticism.

White pushed back.

The money could be broken up into three different buckets, he said. One was cash for fronting financial aid and other expenses. Another was for facilities. And the third was a rainy-day fund that looks eye-popping in size at first glance but is actually only enough to run a system of Cal State’s size for a few weeks.

Now, with the pandemic threatening revenue of all types, many institutions will be relying on cash reserves and rainy-day funds to carry them through economic shocks without having to drastically cut services.

“We’re stable and we have a path forward that is not catastrophic,” White said.

The Way Forward

It’s important to note that White’s high-profile decision on virtual instruction this fall didn’t mean students weren’t returning to campus. Like many other institutions, universities in the Cal State system housed some students who needed to live in dorms and were not spared from COVID-19 outbreaks.

Individual campus plans varied based on a number of factors, including geography and footprint. For example, in late August, the Los Angeles Times reported that Cal Poly Pomona would be offering just 2.5 percent of course sections on campus, with fewer than 500 students living on campus. Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, on the other hand, was offering 13 percent of its sections in person with up to 5,980 students living on campus -- 70 percent of capacity.

The virus still spread among students. Weeks after the fall semester began, Cal State’s Long Beach, Chico State and San Diego State had all reported outbreaks, often among students living off campus. Some employees had called for stronger protocols from the system.

At the beginning of December, White and Castro urged campus presidents to delay their limited face-to-face instruction for as long as possible in the upcoming spring semester because of the COVID-19 surge that was hitting the state and country.

With the pandemic still unfolding, White is realistic about the difficulties ahead for his successor.

Thanks in part to reserves, the system has so far been able to avoid large-scale layoffs. But permanent state appropriations cuts loom, depending on what stimulus packages emerge from Washington, D.C. White stopped hiring for nonessential positions even as he decided not to raise tuition, he said.

He’s looking at the disruption as a three-year issue. Next year will be more difficult than this one. By year three after the pandemic started, recovery might be expected.

Castro has named as a top priority reaching the goals in the Graduation Initiative 2025. So too is securing public funding and building upon technological innovations prompted by the pandemic.

The Cal State system, like higher education, is in a moment of change, with new trustees, new presidents and a new chancellor entering. It faces new challenges and opportunities brought on by the pandemic. For example, Castro noticed that many high-achieving students who might normally travel for college are staying closer to home. Will that continue?

“We’re such a high-value system that it’s a very compelling option for students,” Castro said in September. “That may change the dynamics in higher education.”

If it does, what will Cal State need to do to provide widespread, affordable access to four-year degrees?

When numbers were tallied across the system, concerns about a widespread enrollment downturn tied to the virus didn’t come to fruition. By October, the system was reporting its largest-ever student body in the fall term -- 485,549 students across its campuses, about 3,600 more than the previous year and 1,200 more than the record from 2017.

More than half of the system’s campuses were reporting gains. Many of those suffering losses were in more sparsely populated Northern California, where they tend to draw students from farther away than some of the system’s other institutions.

The overall strong fall enrollment picture wasn’t the result of any decision made in recent months, White said. The system’s strength during this crisis was made possible by the past.

“This is a moment in time that reflects the last five or six years of effort,” he said. “On the Graduation Initiative, on telling the CSU story in ways that it wasn’t told before.”

In a way, the last year has been the culmination of a longer story, one through Riverside, Idaho, Oregon, Canada and Argentina.

While moving into a new home last January, White came across pictures of his parents and was struck by the fact that he’d built a long academic career after his parents gave up so much to leave Argentina. All of their possessions were in a wooden cube measuring about 3-1/2 feet across, White said. He still has the lid, which bears evidence of a party held in Argentina before his family departed.

“People wrote nice things, and some not nice things about being a horse’s ass,” White said, before talking about his father. “He deserted his family, his friends, his job, his house, his community, to get his kids in a place that educated differently.”

“He didn’t need vindication,” White said. “But it kind of feels good at this point.”