You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Nadia Bormotova/Getty Images

Earlier this week, the National Academy of Sciences released a consensus report on the experiences of women in the academic sciences during COVID-19. The upshot of that report and others on the same topic is that the pandemic has disproportionately hurt the careers of women, especially mothers, who now require targeted, equity-based interventions.

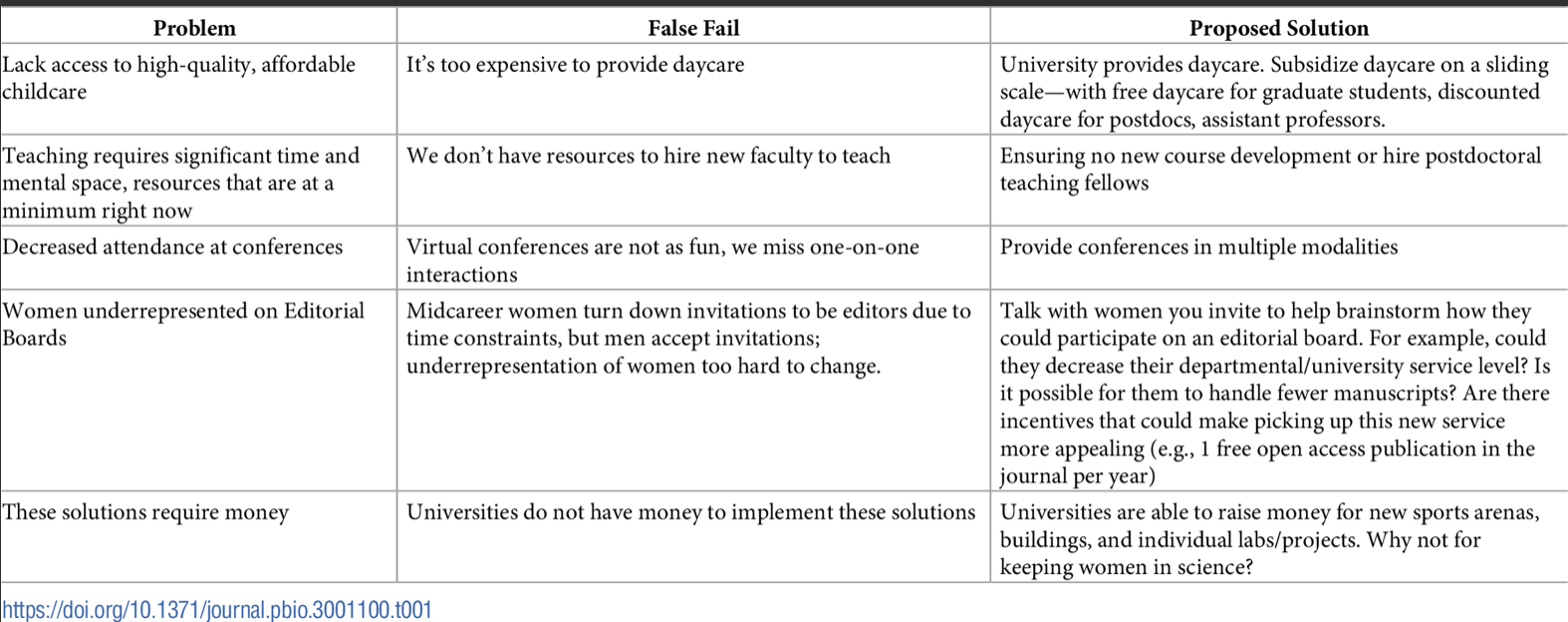

While that publication is deliberately short on solutions, focusing instead on further research questions, a new paper in PLOS Biology is long on them. And unlike many of the department- or campus-based ideas that have been floated or fielded during the last year, this set of solutions is wide-ranging: mentors, college and university administrators, scientific societies, publishers, and funding agencies are all called on to do their part.

"The issues mothers face are not at universities alone," said lead co-author Robinson Fulweiler, professor of biology and Earth and environment at Boston University. "The point is, everyone needs to work towards the goal of providing equity." A more equitable system requires "a multipronged approach," she added.

Not all solutions require serious financial investment. Yet the paper certainly makes the case that the sciences can’t afford to lose women through attrition by not supporting them. It also makes the case that the sciences have much to gain by adopting solutions to long-term problems that the pandemic revealed to be untenable.

Co-lead author Sarah Davies, assistant professor of biology at BU, said, "We've provided fairly concrete actions in our paper that range in their fiscal investment."

If all "spheres of influence got on board," Davies continued, "that would lead to more rapid change -- and I think it would help retain academic mothers, specifically mothers of color, as well as other marginalized groups in the longer term.”

On-Campus Solutions

First and foremost, Fulweiler, Davies and their colleagues advocate for “affordable, high-quality childcare,” citing research showing that women re-enter the workforce and children benefit with this support. Colleges and universities “should provide on-campus daycare, or subsidies for off-campus daycare, as well as funds for additional childcare support when options are limited by social distancing restrictions," the authors say.

Of course, these facilities should also prioritize COVID-19 testing and general safety. And this childcare assistance should be available not only to faculty members but also to staff members, postdoctoral fellows and graduate students “who are facing the same challenges on much lower salaries. We stress that all of us -- regardless of academic position -- can push for this goal, and those in power should be working tirelessly to do so.”

On mentoring, the authors say that supporting women with childcare duties begins before the child joins the family.

“Make it clear that you are wholly supportive of all personal choices and lifestyles, including family units with or without children, and that you value and also strive to achieve a healthy work-life teeter-totter,” the papers advises mentors. “This is an emotional conversation even without the backdrop of a pandemic and keeping clear lines of communication open is essential. We recommend having weekly meetings that cover topics beyond research such as mental health/self-care.”

Mentors of women of color should pay special attention to the extra concerns their mentee parents carry, according to the paper, including those about belonging: “COVID-19 has caused an increase in isolation of [mothers of color] who did not feel supported before the pandemic and already struggled with acceptance in a racist and sexist system.”

Over all, the paper advises mentors to initiate discussions with mentees about "developing flexible timelines for both short- (e.g., lab work) and long- (e.g., graduation date) term goals in such a way that planning is viewed as positive, proactive and supportive." Outsourcing sample analysis or hiring technicians to complete field or lab work could also help mentees meet the demands of a research project while learning to “juggle school and work with childcare.”

Mentors need to be familiar with institutional parental leave policies, as well, in order to help mentees navigate their options and make informed decisions, the paper says.

What about university administrators? The paper says department chairs, deans and provosts “wield enormous power over how faculty, students and staff navigate parental duties under normal circumstances through the establishment and enforcement of policies and procedures.” And while COVID-19 has necessitated rewriting policies, administrators "should not make gender- or race-neutral policies because the effects of the pandemic are not neutral across race or gender."

Departmental chairs at research-intensive institutions, in particular, should allocate flexible funds to support the research productivity of academic mothers, especially mothers of color, according to the paper. And as faculty productivity is directly related to graduate students’ and postdocs’ productivity, parental leave for graduate students and postdocs “should not be the burden of the primary investigator.” Grant agencies and university administrators must provide funding for basic leave "in order to ensure that the hiring of womxn scientists is not disincentivized."

Department chairs at teaching-intensive institutions, meanwhile, should lighten academic mothers’ teaching loads by providing course releases or eliminating their new course development duties. Faculty should also be required to describe the special circumstances they face during COVID-19 in their performance evaluations, the paper says.

Instead of one- or especially multiyear tenure-clock stoppages, which can delay career and salary progression, the paper suggests targeting the scope of the tenure review to years not affected by the pandemic. Another solution is “working to adjust expectations and requirements for the traditional tenure period," rather than prolonging it.

Additionally, as COVID-19 has disrupted individual professors’ specific research projects differently and on different timelines, the authors recommend that all institutions incorporate a “COVID-19 disruption” statement in tenure and promotion files, “with explicit instructions for external reviewers and internal review committees to consider inequalities generated by the pandemic.” Templates should even be provided, with “clear instructions and objective criteria for limiting biases that can arise when evaluating tenure packages.”

Fulweiler, Davies and their co-authors also ask institutions to relieve academic mothers of service responsibilities during COVID-19, then make that explicit in their personnel files and review processes -- and reward professors who then pick up those service duties in their own reviews.

Lab start-up expiration dates should be removed or extended, the paper also suggests, as “removing time constraints on startup funds allows womxn to make financial decisions about their labs within a time frame that works for their situation.” Even better, the paper says, universities can provide support to offset "lost start-up" in the form of research assistant or technician salaries, and associated expenses, which principal investigators continued to pay throughout lab shutdowns. Such funds could initially come from fundraising efforts from alumni, or from diversity, equity and inclusion funds within the larger administration -- then “be built into university budgets going forward to support those mothers who will face ongoing challenges, specifically womxn of color.”

Mothers who are already tenured and seeking promotions shouldn’t be left out of policy changes, either, the authors caution, as women are already most severely underrepresented at the full professor level. Deans and provosts therefore “need to provide clear promotion guidelines and policies while also including specific COVID-19 policies to minimize delays to promotion.”

Off-Campus Solutions

Beyond campus, the paper says that scientific societies may have been reluctant to embrace virtual conferences at first. Yet disability and diversity advocates have “long argued that virtual meetings have the opportunity to reach larger audiences and promote inclusion.” Indeed, the paper continues, the "sudden shift to virtual meetings has allowed many societies to experience the benefits and work through logistical challenges."

Ultimately, societies should consider “how to retain elements of virtual meetings and blend them with traditional meeting schedules when in-person conferences resume,” the authors urge. And now more than ever, it is “important to prioritize womxn, especially BIPOC mothers, to give plenaries and invited talks at virtual meetings.”

Scientific societies should also continue to expand efforts to diversify their governing boards, the paper says. Further, because of the “instability and shifting schedules associated with childcare and work during COVID-19, virtual and/or asynchronous communication for society business would provide much needed flexibility.” These societies would also do well to invest in more early-career members, especially women of color, through research awards, travel grants or publication funds “to offset costs associated with publishing in their journals.”

Flexibility for mothers, including on societies’ publication deadlines, is key -- as is enhancing their networking opportunities, the authors say.

“As we have experienced through preparing this article, many mothers with little free time can join forces for productive and impactful collaborations,” they wrote. “Because shared experiences allow for empathy, support, and realistic expectations, especially under our current circumstances, society-supported symposia or networking activities that bring together mothers in related fields could generate new and innovative research collaborations that are supportive, satisfying, and more productive.”

Similar to promotion and tenure, the paper advises societies to encourage academic mothers to include a COVID-19 impact statement in applications for travel and research awards. Childcare costs could also be factored into these funds, it says.

Regarding publishers, the paper notes that manuscript submissions by female researchers to preprint servers across disciplines dropped significantly or increased less than their male colleagues' soon into the pandemic. And due to the “time lag” of the publishing process, “we expect these disparities will further increase throughout the course and aftermath of the pandemic.” Publishers and editors can help “counterbalance these long-term detrimental effects on equitable science.”

Helpful measures already being considered or adopted include expediting women’s submissions and prioritizing them during the peer-review process, and extending deadlines for reviews and revisions, the paper says. Open-access fee waivers could also be extended to a “certain proportion" of manuscripts led by mothers with childcare responsibilities during COVID-19.

To facilitate these interventions, journals could add a self-reporting feature on their submission pages for mothers to identify themselves, the authors suggest. Similarly, “manuscript images on journal covers help to highlight research and efforts could be made to make studies by mothers more visible.”

As men still dominate editorial boards and are more often invited to submit papers than are women, journals could “invite and incentivize womxn to join editorial boards and recruit them to apply for editor-in-chief positions.” Editors can also amplify female voices by inviting them to write review or preview articles, which tend to attract higher citation rates.

Even before the pandemic, women were submitting fewer grants applications than men. So funding agencies could easily facilitate no-cost extensions on grants, given current circumstances, the paper says. It will be equally important to create flexibility in “funding rules for multiple no-cost extensions due to the multiyear nature of the pandemic,” it continues.

“We recommend that agencies consider what steps can be taken to reduce the paperwork burden associated with sequential applications, which are disproportionately needed by PIs with additional care-giving roles,” the paper also says. “A streamlined mechanism for proposing scope of work revisions and rebudgeting requests would allow academic mothers to focus efforts on progressing research.”

Funding agencies could consider making supplemental awards during extensions, as well, the authors suggest, “to allow for additional salary support for grant-funded project personnel to facilitate completion of the original scope of work when research is able to resume safely.” If any additional funds are available, agencies could also consider developing short-term bridge funding awards to support academic mothers at all career stages, as mothers are more likely than fathers to leave full-time STEM positions due to increasing childcare needs.

Given that disruptions could impact how academics are assessed for research funding in the future, agencies, like institutions and societies, could allow them to include COVID-19 disruptions statements in future grant applications.

The authors implore universities, societies and scientific leaders to "carefully consider where and when they could leverage their power to implement the solutions presented" and not to forgo action because something hasn’t worked in the past.

As for the many studies that have documented declines in women's productivity during COVID-19, Fulweiler said that "gathering data on the issues mothers, and mothers of color, in particular, face is helpful. Alternatively, or additionally, we can listen to what mothers have been saying for a very long time."

Fulweiler added, "This is a solvable problem. While more data is a bonus, we can -- we must -- act now."

Emphasizing that the effects of COVID-19 on academics’ careers will outlast the pandemic itself, Davies said, “Treating COVID like a one-year disruption is shortsighted. Anyone who knows how research works understands that it can take years to gather preliminary data to develop a proposal that is fundable, so this is not a simple blip in our research productivity.”

More Than the ‘Performative’

While the paper describes a comprehensive approach to leveling the playing field for academic mothers during COVID-19 and after, Davies said there is a need for someone, or something, to "lead the charge."

“There is a lot of talk, but so far, to my knowledge, these discussions have largely been performative,” she said. “It seems like universities are just waiting to see what their peers are doing instead of acting, even though the evidence that women are being more impacted than men was demonstrated really early on in the pandemic.”

More broadly, she continued, “COVID has just laid bare the inequities that have always existed in the academic system.” Prior to the pandemic, women and other marginalized groups were doing just enough to “stay in the game.” Now there are "literally not enough hours in the day to keep up, and every day that passes, we fall further behind.”

Along with other colleagues, Davies and Fulweiler have another paper under review, called “Shifting Our Value System Beyond Citations for a More Equitable Future.” This paper takes aim at the success and impact metrics in science that “are based on a system that perpetuates sexist and racist ‘rewards’ through prioritizing citations and impact factors.”

Such metrics are “flawed and biased against already marginalized groups and fail to accurately capture the breadth of individuals’ meaningful scientific impacts,” the paper says. It advocates shifting away from an “outdated value system” and advancing science through the “principles of justice, equity, diversity and inclusion.”

Like the COVID-19 solutions paper, this one urges “collective efforts supported by academic leaders and administrators to drive essential systemic change.”