You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Polina Zimmerman/Pexels.com

Maybe more than ever, faculty members are talking to students about mental health. Professors feel a responsibility toward students who are suffering and would welcome better -- even mandatory -- training on the topic, according to a COVID-19-era report from Boston University’s School of Public Health, the Mary Christie Foundation and the Healthy Minds Network.

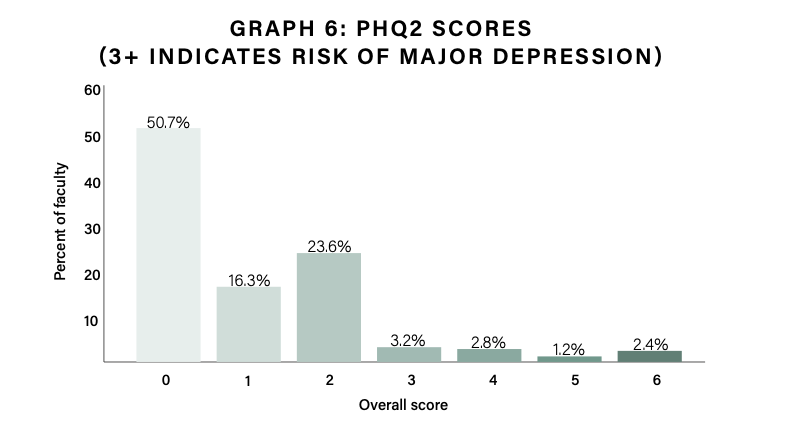

At the same time, many faculty members report suffering from some of the same health challenges their students do: nearly 30 percent of surveyed professors report having two or more symptoms of depression.

Two in 10 professors agree that supporting students in mental or emotional distress has taken a toll on their own mental health. About half believe that their institutions should do more to support the psychological well-being of the faculty.

All of this “warrants a strong response by institutional leadership to better support faculty as they communicate with students about their mental health,” the report says.

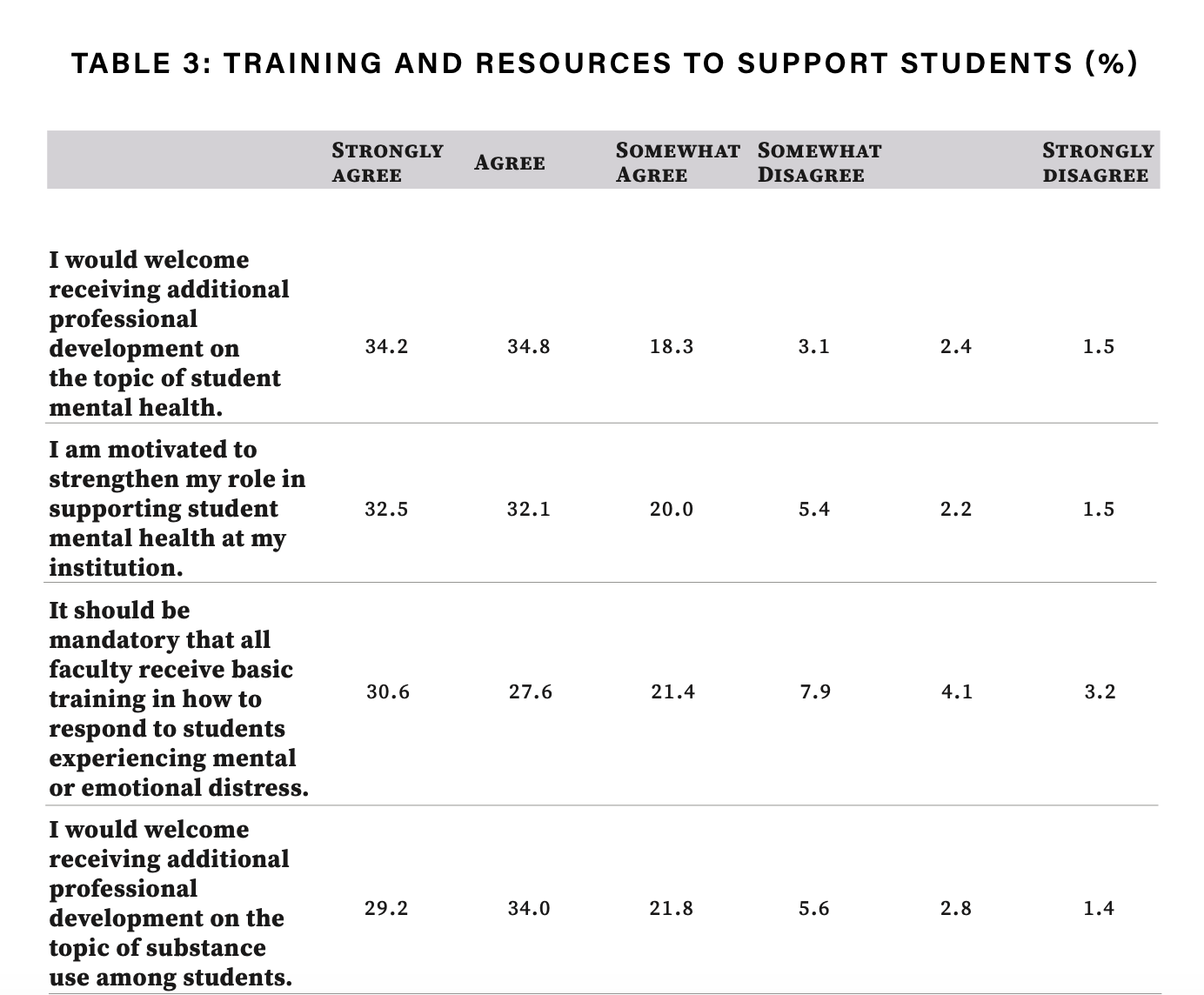

Suggestions include providing faculty members with more training and straightforward resources on student mental health issues, such as mental health statements to include in their syllabi. This information should speak to student substance abuse issues, as well, according to the report, as professors say they’re even less prepared to help students with this topic. The campus climate for students of color also requires urgent attention.

"There are so many faculty who are sincerely interested in helping students recover and move forward," said Karen Oehme, director of Florida State University's Institute for Family Violence Studies and director of the steering committee for the national Academic Resilience Consortium, which promotes resilience for students and institutions.

Oehme wasn't involved in the new study but said after reviewing it that universities have already had to "bend and stretch and accommodate all of these changes that they never anticipated." Going forward, she said, they "will have to prioritize well-being of their faculty, students and staff."

Advocates, Not Counselors

The new report's primary author, Sarah Ketchen Lipson, assistant professor of health law policy and management at Boston University, said this week, “I certainly don't think faculty should be mental health professionals, trying to fill gaps in terms of students’ mental health needs.” Yet the data make clear that an ever greater proportion of the faculty “actually do really genuinely want to support students, and there’s reason to lean into that.”

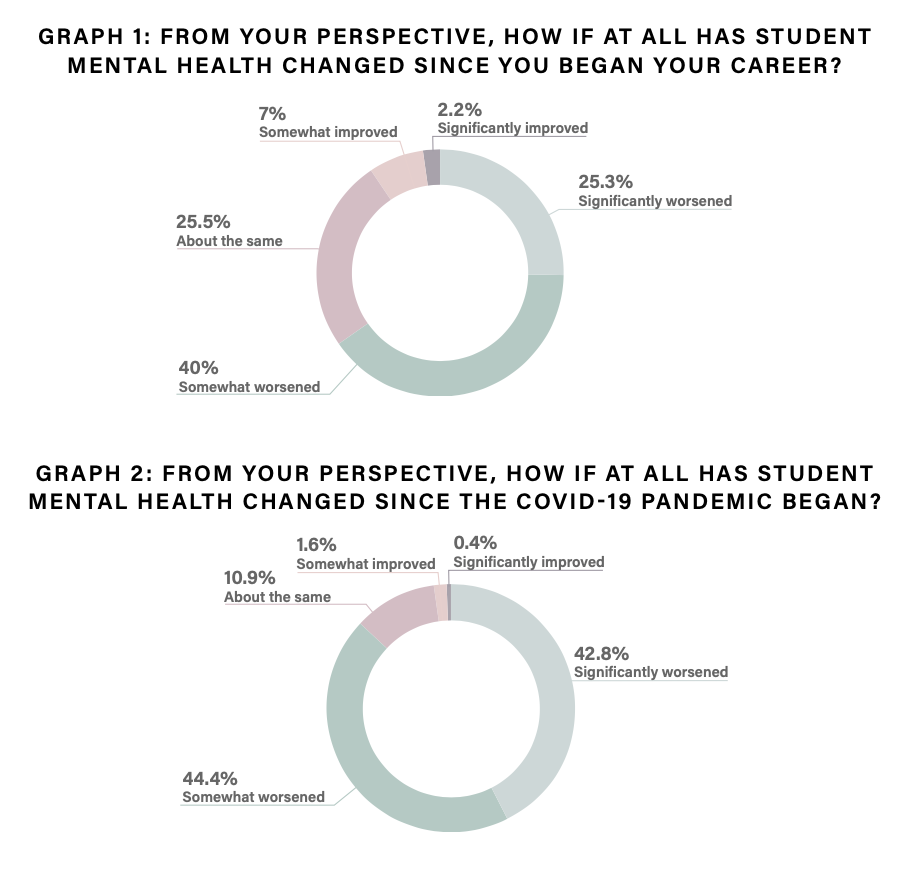

Even before the pandemic, data on student mental health from the last five to 10 years showed increased levels of depression, anxiety and reports of suicidality, Lipson said. For obvious reasons, the pandemic exacerbated these issues. Another recent study in which Lipson was involved found that 83 percent of students said mental health had impacted their academic performance, for instance.

Faculty members are struggling, too. Burnout is high, perhaps especially among parents. So Lipson said that she hopes the new study’s findings on faculty mental health catch the attention of presidents and provosts, who are positioned to make policy changes to help them.

As for the implications of her work on faculty-student interactions, Lipson said, “There’s a lot of really low-hanging fruit that we can be thinking about in terms of how we can be flexible with students, how we can convey to them that we want them to succeed, and bring in this empathy and humanity to our instruction. It’s not written into the job description, but it really is fundamental to teaching young people.”

Students’ college experiences are "going to be shaped by their mental health and well-being," she said, "and faculty have a role to play in shaping that -- and then helping students succeed academically by trying to refer students in need to available services so that they can benefit as much as possible from their learning experience with faculty.”

Other Findings

The study also found that some 87 percent of professors say student mental health has “worsened” or “significantly worsened” during the COVID-19 pandemic. Just about 80 percent of professors have had one-on-one phone, video or email conversations with students in the past 12 months regarding student mental health and wellness.

Source: Lipson et al.

These kinds of interactions are gendered to some degree, the study found. Around 85 percent of female and transgender or non-gender-conforming professors report having had these one-on-one conversations over the past year, compared to 71 percent of male professors.

The findings have racial dimensions, as well: one in four professors believe that their institution is at least somewhat hostile toward students of color. More than half of Latinx professors surveyed say so, as do 39 percent of Black respondents.

Data collection started in January, following a “turbulent year marked by the pandemic as well as racial injustices,” the report says. Calling the data on race and hostile climate highly “concerning,” the researchers said climate issues “can further exacerbate the mental health issues of these students and may make faculty less likely to refer students to available mental health resources on campus.”

While the majority of professors are engaging their students, or being engaged by their students, on issues of mental health, just 51 percent of professors say they have a clear understanding of how to recognize a student in emotional or mental distress. An even smaller share of professors (29 percent) say they know how to recognize students with a substance abuse disorder.

Seeking to better understand the faculty perspective on student mental and behavioral health, researchers gathered online survey responses from about 1,700 faculty members at 12 American colleges and universities, ranging in enrollment from about 2,000 students to 20,000. Respondents teach undergraduates, graduate students or both.

Faculty members with four to six years of teaching experience are most comfortable discussing mental health issues with students, while faculty members with 10 to 15 years of experience are least comfortable, according to the survey. Knowledge of institutional resources regarding mental health seemed to correspond more linearly with teaching experience: 42 percent of professors with one year of experience or less agree or strongly agree that they are aware of the mental health services at their institution, compared with 80 percent of faculty with 15 or more years on the job.

Far fewer professors at any career stage say they’re comfortable talking with students about students’ use of alcohol or drugs.

Faculty members “are in need of mental health gatekeeper training, defined as programs designed to enhance an individual’s skills to recognize signs of emotional distress in other people and refer them to appropriate resources,” the report says.

Some 56 percent of respondents say they don’t know if gatekeeper training even exists at their institution. Just 29 percent have participated in any training program like this. Among those, 72 percent found it useful or very helpful.

Sixty-nine percent of respondents agree or strongly agree that they would welcome additional professional development on the topic of student mental health, and the same proportion say they’re motivated to better understand these issues.

While there remains some debate as to the faculty role in student mental health, 61 percent of respondents say training on student mental health should be mandatory.

Asked about their preferences for this kind of training, most prefer online (57 percent), and want it to include general support advice instead of just crisis response (52 percent). Some 46 percent of professors want the training to be self-paced and 42 percent want it to take 30 minutes or less. Forty percent want it to happen during paid working hours.

Beyond training, the clear majority of professors (73 percent) want a ready list of institutional mental health resources, as well as a checklist of things or look out for or warning signs (71 percent). Many also want a short reference guide for how to initiate these conversations, plus a model mental health statement to put in their syllabi.

The survey included a questionnaire about respondents’ own mental health, with alarming results. About 10 percent of professors screened positive for symptoms of major depression on a patient health questionnaire. About half the sample report having at least one symptom of depression. One in five professors agree that supporting students in distress negatively impacts their own mental health.

Elizabeth Cawley, director of national mental health strategy at Studentcare/ASEQ, a Canadian administrator of student health plans, said, “Student mental health has absolutely declined during the pandemic, even more so than in the general adult population.”

Cawley said she wasn't surprised by Lipson's findings about faculty-student interactions, either, citing prior research finding that professors want to help students in this way but feel underprepared.

Given the importance of faculty and the frequency of faculty-student interactions, Cawley said, mental health literacy training, or gatekeeper training, should be mandatory for all professors. This sends the "message that an institution recognizes the key role that faculty play -- and that many students will approach a professor for advice or support before going to traditional support services."

Mandatory training would also serve to decrease some of the "stress and anxiety that faculty face when dealing with issues of student mental health."

In any case, Cawley said, “A vibrant campus community doesn’t stop with supporting students. Faculty and staff are often overlooked, and yet they play such a crucial role in supporting students. The saying, ‘You need to put your own mask on before helping others’ comes to mind, because if faculty are struggling, they won’t be able to support their students.”