You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Muradoglu et al.

The more a field is perceived to value raw talent, or “brilliance,” the more women -- especially those from underrepresented groups -- struggle with impostor syndrome. That's the unfounded feeling that one's professional place is unearned. The same is true of early-career academics. Both findings are from the biggest study of impostor syndrome yet, published today in the Journal of Educational Psychology.

Impostor feelings correlated with a lower sense of belonging in a field and lower self-efficacy, the study also found. While the findings are correlational, not causal, the authors say their work has implications for diversity and climate efforts across fields. This is because academics who don't think they belong in a field may be unlikely to stay in it. Moreover, the authors say, impostor syndrome shouldn't be looked at as an individual problem but a workplace one.

“We should be having earnest conversations about how fields and workplaces can be more welcoming,” said lead author Melis Muradoglu, a Ph.D. candidate in psychology at New York University. “Rather than placing the responsibility on the individual, the focus should be, ‘What in the field or workplace can be changed so that people don’t question their ability and success?’”

The study doesn’t focus on which fields value brilliance, but rather the relationship between perceptions of how much brilliant matters, impostor syndrome and scholars’ gender, race and career stage. But Muradoglu said that her and her colleagues’ work, along with prior research, shows that these fields include philosophy, math and economics.

What the Researchers Did

For their study, Muradoglu and her colleagues sampled 4,870 academics at multiple career stages in more than 80 fields, from the humanities to natural and social sciences to medicine. Academics at nine unnamed research-intensive universities, both public and private, got an email invitation to complete an anonymous online survey in exchange for a $5 Amazon gift card. About half of the participants were male and half were female. Some 11 percent were underrepresented minorities.

The survey included questions about impostor feelings, belonging and self-efficacy, all with respect to respondents’ current fields. Respondents answered additional questions about their perceptions of their fields’ brilliance orientation, or to what degree they perceived their fields to link success to raw, untutored talent. The questions about impostor syndrome were adapted from a previously validated scale and asked respondents to rank their identification with feelings such as, “I am afraid people important to me may find out that I am not as capable as they think I am.” Higher scores on this part of the survey indicated stronger impostor feelings. The researchers assessed respondents’ sense of belonging in their fields and self-efficacy in a similar manner; one question on the self-efficacy questionnaire asked respondents to rate their agreement with the idea that they could succeed at any professional endeavor they set their minds to, for instance.

Regarding the brilliance question, respondents completed an eight-item, field-specific ability beliefs questionnaire. Some items asked to what extent brilliance and giftedness were required for success in respondents’ respective disciplines. Other items asked about how hard work and effort factored into success. Questions asked respondents to report their own beliefs and, separately, those of others in their fields. Higher scores in this part of the survey meant a higher belief that brilliance matters.

What the Study Found

Next, the researchers studied the relationship between participants’ scores on different parts of the survey and their gender, ethnicity and career stage. Echoing other studies linking gender to impostor syndrome, the authors here found that women reported stronger impostor feelings than did men. Underrepresented minority academics didn’t report significantly stronger impostor feelings than white or Asian academics, but graduate students and postdoctoral fellows reported significantly stronger impostor feelings than did faculty members.

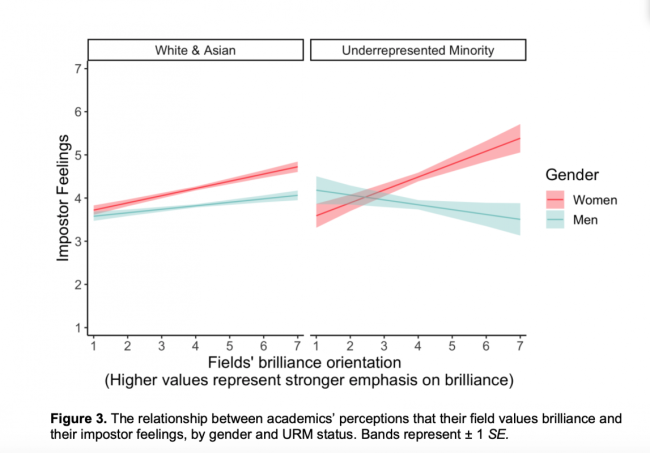

Incorporating the brilliance question into their model, and completing an intersectional analysis, the researchers found a clear connection between fields perceived to value untrained intellect and women and early-career researchers experiencing impostor syndrome. Women from underrepresented backgrounds in these fields were most likely to experience impostor feelings.

All this highlights “the substantial extent to which the impostor phenomenon is a function of the contexts that academics have to navigate rather than being a symptom of inherent psychological vulnerabilities,” the study says. “This is a critical step forward in our understanding of this phenomenon.”

Interestingly, men from underrepresented backgrounds in brilliance-oriented fields did not report higher feelings of being an impostor. Instead, the study says, underrepresented women in these fields “seem to experience a distinct, heightened form of oppression that emerges at the confluence of their identities.”

Muradoglu said it’s important to remember that talking about brilliance-oriented fields means talking about belief systems. Beliefs do make up the ethos of a field, she said, but not necessarily what’s actually required for success.

What is impostor syndrome, technically, since it’s often used casually to describe feeling out like a proverbial small fish in the big pond of academe? Muradoglu said the core belief is that one’s professional success is unearned, despite objective evidence to the contrary. People may then “view themselves as less capable; they may think that people in their professional sphere might eventually quote-unquote unmask them and discover that they’re not very capable,” she added.