You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

William Atto

University of Dallas

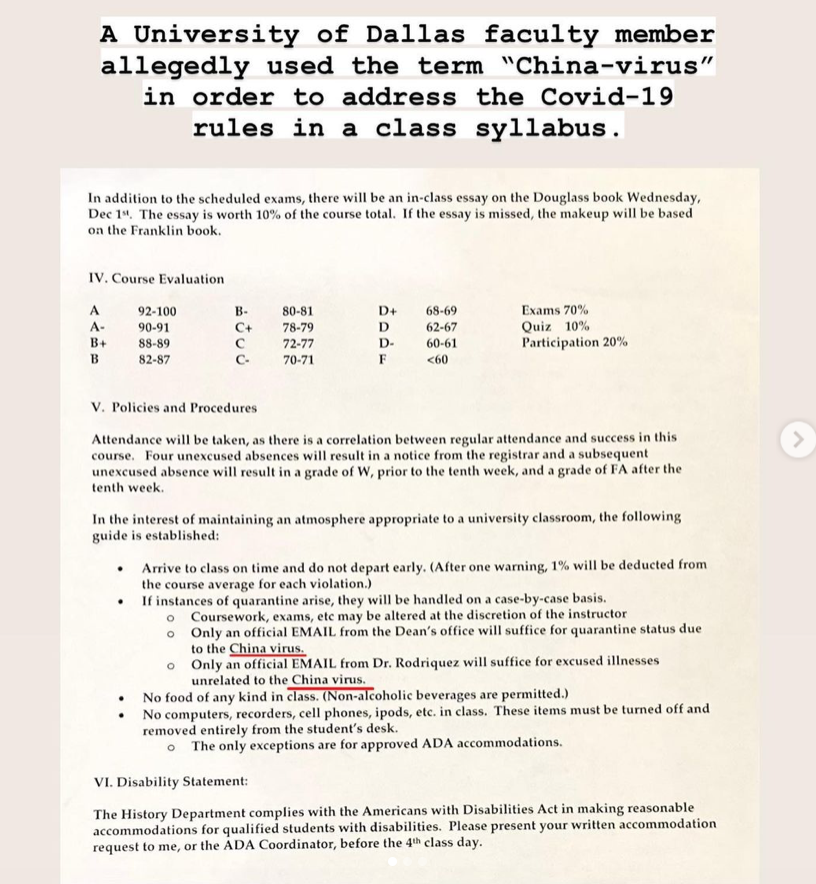

A professor at the University of Dallas who used the term “China virus” in his syllabus this semester was told to change the wording to “COVID-19” after students objected.

“Only an official email from the dean’s office will suffice for quarantine status due to the China virus,” the original syllabus said in one of two similar uses of the term.

The terms “China virus” and “Wuhan virus” are widely considered racially insensitive, and their usage have been linked to an uptick in hate crimes against Asian Americans during the pandemic.

No student complained to the professor or his chair directly, according to public accounts of what happened. But the syllabus quickly made its way to social media, where commenters said the term was racist.

In an Instagram post, the university’s Asian Student Association shared a screenshot of the document, saying that the term “China virus” promotes “discrimination against Asians and Asian Americans since it condemns them to be the cause of the virus. The influence of this accusation led to a spike of mistreatment (both passive and violent) and xenophobic attacks against Asians around the world.”

Citing the #StopAsianHate online awareness campaign, the post also says that using “China virus” in a learning environment “is inappropriate not only to Asian American students but also to all minority students.”

Citing the #StopAsianHate online awareness campaign, the post also says that using “China virus” in a learning environment “is inappropriate not only to Asian American students but also to all minority students.”

William Atto, the associate professor of history at the center of the case, complied with the private, Roman Catholic university’s order that he update the syllabus. He also emailed students to explain the change.

Atto did not respond to a request for comment. But his department chair, Susan Hanssen, is speaking out, saying that now that “cancel culture has come to our campus,” she “will not be silent.” She shared her concerns about the incident in an opinion piece for The College Fix, a conservative news website about higher education.

Hanssen wrote in the piece that even though no student objected directly to the syllabus, Instagram “exploded with accusations of racism via a left-leaning UD alumni group’s account” by the end of the first day of classes. “To say that they were waiting for the least excuse to pounce is putting it mildly.” Social media “trolls shrieked that, like Donald Trump, Atto put ‘a target on the backs of Asian Americans,’ and claimed the recent increase in anti-Asian violence was due to Trump’s use of the phrase ‘China virus.’”

Stating that these “trolls” had “missed the mark,” Hanssen wrote that as a historian, Atto “understands history is complex, and it is not easy to place the oppressors and the oppressed in easily labeled identity politics categories.” Where were these “Instagram trolls for the past 20 years as Atto taught on the history of the savage Japanese ‘Rape of Nanking’?” she asked. “The Maoist Communist regime’s brutality against its Chinese population? America’s exclusionary acts against Chinese immigrants?”

Hanssen suggested that the case could have ended when Atto “immediately acquiesced” to the university and changed the document, but that his “sin of candid communication” was amplified by a consequent report in the student newspaper, The University News. Disagreeing with some aspects of that article, Hanssen said that the coverage in itself put Atto on “public trial instead of it simply being a ruckus hidden in the bowels of Instagram.”

Hanssen further alleged that the newspaper, via its consistent coverage of race, diversity, equity and inclusion issues, seeks to “effectively dismantle one of the few last bastions of a faithfully Catholic liberal arts education.” This kind of coverage “fuels the stream of more diversity surveys, hiring more diversity officers, spending more money and providing more hand-wringing fodder for diversity, diversity, diversity.”

Guessing that she’ll be the “next target,” Hanssen wrote, “My prudent faculty friends tell me that when they come to get me, I should take my stand firmly on the book of Genesis: ‘Male and Female He created them.’ Don’t risk your career over a quibble about naming the virus.” Yet even as personal pronouns and gender remain Hanssen’s bigger concern, she said that the “‘China virus’ is not a bad hill to die on if it simply asserts the right to control one’s own language. The abuse of language is the abuse of power.”

It's “time for this Catholic university to take a stand,” Hanssen said. She asked if the university posed big questions such as “What is courage?” in an “abstract, theoretical way,” or if it’s also a “place that gives students a living model of the virtues they verbally espouse.”

The university declined comment on the matter Tuesday.

Hanssen said via email that she’d like to see the university clarify that there was no direct student complaint, beyond what appeared on social media, and to “apologize for caving in to social media attacks on a professor.”

She also said she expected “a more robust defense of Prof. Atto from one of the nation’s finest Catholic conservative colleges. Our alumni, parents and students rightly expect us to challenge the regime of political correctness rather than kowtow to it. UD says that they will defend our right to use male/female pronouns when the times comes, but ‘cowardice today is poor promise of heroism tomorrow’ (Quoting Dominican Sertillange)” [sic].

This isn’t the first time a professor has referred to COVID-19 as the “China virus” or “Wuhan virus” in class. Syracuse University put a professor on administrative leave last year because he included a note on the “Wuhan flu or Chinese Communist Party Virus” in his chemistry syllabus. Syracuse also publicly condemned the “derogatory language” as offensive to Asian students who have experienced hate speech related to the pandemic, and as generally “damaging to the learning environment.” Syracuse alleged that the professor had created a hostile learning environment based on national origin, against expectations for ethical conduct included in the Faculty Manual.

Many on campus applauded the move, as the term “Chinese virus,” like other stigmatizing language, has been shown to perpetuate the sense that Asian Americans are perpetual foreigners, putting them at greater risk of discrimination.

Some free speech advocates, including the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, criticized Syracuse. In a letter to the university, FIRE said that the university was curtailing faculty expressive rights and that the syllabus is an “academic forum” in which professors are free to discuss controversial topics.

Keith E. Whittington, William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Politics at Princeton University and chair of the Academic Freedom Alliance’s Academic Committee, said there’s “nothing wrong with a professor deciding voluntarily to change the language on a syllabus after an issue was raised by a student or administrator.” Responding and adapting to criticism “is part of the give-and-take we would expect on a college campus,” he said, “assuming the criticism is not backed by a threat of sanction.”

It’s unclear exactly how the University of Dallas told Atto to change his syllabus, but the switch wasn’t wholly voluntary. Whittington said that syllabi are something of a “mixed venue,” meaning they can include both university policies and professors’ own course material. Generally, he said, a professor’s content “would seem to be protected as a matter of academic freedom, just as other course content would be.”

The question then becomes “whether this particular content somehow fell outside the bounds of protected academic freedom,” he said. A university may want to assert that references to the “China virus” are discriminatory harassment and therefore not protected by academic freedom, Whittington continued, but he said that in this case “such a claim seems very dubious.”

Even if “China virus” offends some, he said, “the simple use of the phrase on a syllabus cannot be understood to rise to the level of legally actionable harassing conduct.” And a university harassment policy written “so broadly as to prohibit such a generalized expression of ideas” would “significantly impinge on traditional understandings of academic freedom.”

Jonathan Friedman, director of free expression and education at PEN America, had a similar take, saying that university leaders might “try to educate the professor in question about this, but they shouldn’t be issuing diktats that he make this change or else fear reprisal.”

Atto’s is a case in which the “best outcome can be achieved by protecting the speech of everyone involved,” Friedman also said.

A professor “must have the academic freedom to put whatever language he chooses on his syllabus, just as the students must have the right to use their speech to call attention to it, whether on social media or in the student newspaper,” he said. At the same time, “some speech is harmful, and especially in the context of rising hate crimes, it behooves professors, in their position of leadership and authority, to understand how their choices of expression on a syllabus are received by their students.”