You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

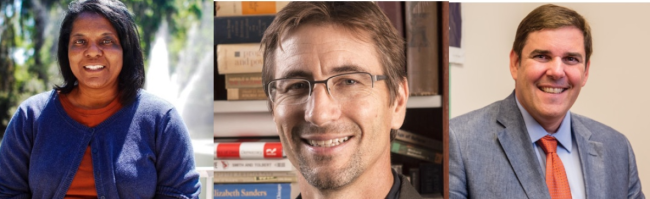

From left: Sharon Austin, Daniel Smith and Michael McDonald

University of Florida

Following intense pushback, the University of Florida now says the three professors it blocked from testifying in a voting rights lawsuit against the state may participate -- if they do so on their own time, for free, without using university resources. The university also says it’s appointing a task force to study its conflict of interest policy, which was last updated a year ago, to ensure “consistency and fidelity.”

This partial softening of the university’s stance went down like a lead balloon Tuesday with the professors and the university’s other critics, who continued to accuse Florida of violating academic freedom and the First Amendment.

News also broke late Tuesday that five more professors had accused the university of limiting or blocking their participation in additional legal challenges to the state, including two against Florida's ban on mask mandates. At least one of those professors said he would not have been paid for his expert work, suggesting that UF's opposition to professors speaking out against the state isn't really about whether they're getting paid to do it.

In a joint statement, the first three professors’ lawyers, David A. O’Neil and Paul Donnelly, said, “Historically, faculty from the University of Florida have regularly served as expert witnesses in court proceedings, sharing their expertise on a broad range of topics. Now, when three professors’ testimony may threaten politicians’ political agendas, the university has abruptly ignored its longstanding policy and practice, violating the professors’ First Amendment rights and denying their academic freedom.”

Prohibiting the professors from giving “standard expert testimony, and instead only allowing pro bono testimony, undermines their credibility as expert witnesses and chills their speech,” the lawyers said. “That is why we intend to fight the university’s order.”

Ken Mayer, a professor of political science at the University of Wisconsin at Madison who started a petition in support of the Florida scholars, which was signed by scores of other election-expert witnesses, said, “Allowing expert testimony in a federal case should have been a no-brainer for the University of Florida, and my sense is that they are backpedaling because they know they got it wrong.” Mayer also called the university’s formation of a policy review task force “just a caricature of administrative timidity.”

Regarding the bigger issue at hand -- whether the university is really upholding academic freedom and free speech by now allowing the professors to testify pro bono -- Mayer said, “The pro bono issue is irrelevant, and my understanding is that all three of the professors believed the prohibition [on testifying] was general and not limited to compensated work.”

The three professors in question, Sharon Austin, Dan Smith and Michael McDonald, all political scientists, did not personally respond to questions about the university’s statement through a spokesperson they’ve retained. But McDonald has previously said that whether he and his colleagues were paid to testify was not part of the university’s initial rejection of their request to act as expert witnesses in a legal challenge to SB 90. That’s Florida’s new law limiting mail-in and drop-box voting.

McDonald on Twitter shared a screenshot of his own denial, which says that Gary Wimsett, UF’s assistant vice president for conflicts of interest, deemed his request an “impermissible conflict of interest.”

The university denies employees’ requests to engage in outside activities “when it determines the activities are adverse to its interests,” that denial also says: “As UF is a state actor, litigation against the state is adverse to UF’s interests.”

SB 90 was backed by Florida governor Ron DeSantis and other Republicans. The plaintiffs who are challenging the law say it violates the federal Voting Rights Act and is discriminatory against voters of color. The plaintiffs sought out the three Florida professors to testify as experts on voter behavior and the implications of this new law, presumably with the expectation that this expert analysis would bolster the case against the state. But as Mayer’s petition to the university notes, “Expert witnesses are not advocates, nor do they argue in favor of any particular legal position. The role of an expert witness is to provide answers to specific questions based on data, reliable methodologies, experience and technical knowledge. Their role is to provide information and empirical answers to courts so that judges have the best information available as they evaluate legal arguments.”

Mayer, who also works at a public university, said he’s been an expert witness in both state and federal court, and that while university reporting requirements and potential time limits can trigger “higher scrutiny" in some cases, this work is allowed. That’s not contingent on whether the work is compensated, either, he said.

UF’s own conflict of interest policy doesn’t rule out paid outside work, but says, “Employees must avoid situations which interfere with -- or reasonably appear to interfere with -- their professional obligations to the university.” The policy defines conflict of interest as occurring when an employee’s “financial, professional, commercial or personal interests or activities outside of the university affects, or appears to affect, their professional judgement or obligations to the university.”

The university separately defines conflict of commitment as occurring when an employee “engages in an outside activity, either paid or unpaid, that could interfere with their professional obligations to the university.”

UF has not cited conflict of commitment in limiting the professors’ participation in the case, but this is arguably more relevant to its argument. That is, the university hasn’t said that the professors’ role at the university might compromise or appear to compromise the integrity of their testimony. Instead, it’s suggested that their “adverse” position against the state law might compromise the university, where they are employees.

Bright Lines and a Slippery Slope

In allowing the professors to participate in the case pro bono, then, UF seems to be attempting to draw a bright line between the university as a state-funded institution and the professors as experts. But academic freedom doesn’t work this way, experts say, as professors don’t stop being professors when they’re “off the clock.”

In a second letter to the university about the case, Keith Whittington, chair of the Academic Freedom Alliance’s Academic Committee, and William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Politics at Princeton University, said that the university is trying to draw another kind of “bright line,” that between a professor speaking as a paid expert witness in a lawsuit against the state and “any other instance in which a professor might serve as a paid expert witness.” Yet citing prior case law, Whittington said it’s “constitutionally unacceptable to draw such a line. Indeed, the university suggests that professors can be compensated to speak if they testify in favor of the state but they cannot be compensated to speak if they testify against the state. This is constitutionally unsustainable” under the First Amendment.

Citing additional case law, namely a lawsuit brought by faculty members within the Texas A&M University system who wanted to act as paid expert witnesses in a lawsuit against that state, Whittington said, “There is no constitutional distinction to be made between faculty members serving as paid expert witnesses and testifying pro bono … The fact that an expert witness might be compensated for his or her work does not lessen the constitutional protections for that activity.” The faculty members’ position in that particular case was affirmed by a federal appeals court in 1998.

Regarding academic freedom, which governs free expression in its own way in an academic context, Whittington described a slippery slope: if it’s “contrary to the best interest of the university for a faculty member to be retained as an expert witness in a lawsuit against the state, would it equally be against the best interest of the university for a faculty member to write a book, a scholarly journal article, or a newspaper op-ed criticizing the state’s policies?” And would it matter, he asked, “whether the professor is compensated for the op-ed or receives royalties from the book sales? Is the university proposing to suppress any criticism that members of its faculty might direct against the state unless they do so,” as the university put it, “pro bono on their own time?”

Aaron Terr, a program officer at the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, underscored FIRE’s earlier message to the university about the case, saying that the U.S. Supreme Court has “made clear that a speaker’s rights are not lost merely because they are paid to speak.”

Terr also said there is “nothing unusual about expert witnesses being paid for their service, and UF’s own policies acknowledge that professors may receive compensation for outside activities. The university can no more use this rationale to prohibit faculty from testifying than it could to bar them from writing paid newspaper op-eds.”

At bottom, he said, the university’s decision “still infringes on the professors’ freedom to develop and share their academic expertise.”

Florida president Kent Fuchs and provost Joe Glover said in their announcement of the pro bono news that they want to be “abundantly clear that the University of Florida stands firmly behind its commitment to uphold our most sacred right as Americans -- the right to free speech -- and to faculty members’ right to academic freedom. Nothing is more fundamental to our existence as an institution of higher learning than these two bedrock principles. Vigorous intellectual discussions are at the heart of the marketplace of ideas we celebrate and hold so dear.”

This statement was published before the Miami Herald reported on Tuesday night that four UF professors who wanted to sign an amicus brief in a lawsuit challenging how the state had administered restored voting rights to felons were told last year that they could not identify themselves as faculty members. The university allegedly said this was because such activity involved “an action against the state.”

Another professor, Jeffrey Goldhagen, who studies pediatric medicine, said he was told over the summer that participating in two lawsuits against the state's mask mandate would create a conflict for the university, and that he couldn't become involved. Wimsett, the university's conflict of interest official, reportedly told Goldhagen that “UF is an extension of the state as a state agency, litigation against the state is adverse to UF’s interests." He also reportedly told Goldhagen there was no process to appeal his decision. Wimsett didn't ask if Goldhagen would be paid as an expert or work for free, the professor said, but he'd planned on working pro bono.

Goldhagen told the Herald, “If you deny science and you deny the universities the critical role they play in American society, then you truncate free speech, academic freedom and the dissemination of information.”